It’s bigger. They think it’s deadlier. And its exact location is secret. Scientists have declared the Sydney funnel web – hallowed and feared as the world’s most venomous spider – is in fact three separate species. And one of the spiders, new to science, is a certified monster.

The spider’s sheer size means it could pose an even greater danger to humans than the classic Sydney funnel web. Current antivenom can treat its fatal bite, but scientists are keen to pinpoint differences in venom toxicity in case a more species-specific antidote could be crafted.

The new species, nicknamed “the big boy”, was given the scientific name Atrax christenseni after the Central Coast spider-wrangler who led scientists to its discovery.

That man, Kane Christensen, joined the Australian Reptile Park in 2003 as a volunteer venom milker. Each summer the park near Gosford asks the public to drop off captured funnel webs for the production of antivenom.

Almost immediately, Christensen began to notice a procession of abnormally huge funnel webs, big as men’s palms. They barely fit in the park’s holding jars. People mistook them for huntsmans. When one prowled across a benchtop, you could hear its footsteps.

The giant spiders became sport for the park’s media team. In 2018, the park hailed the arrival of their biggest ever funnel web, dubbed Colossus, and grabbed international headlines. A normal male has a 2.5 centimetre body length. This spider was double that size.

Then came Megaspider, brawny enough to go toe-to-toe with a tarantula, in 2021. Next it was Hercules, a beast with an eight-centimetre leg span packing fangs long and strong enough to pierce a fingernail.

And even Hercules was usurped this season by a 9.2-centimetre arachnid dubbed Hemsworth after Australia’s hunky Hollywood brothers. It was the largest funnel web ever found, the park said.

Behind the scenes, scientists had been working to probe a theory long suspected but hitherto unproven: that these goliaths were a brand-new species of the deadliest spider on earth.

A classic male funnel web (right) and the newly named “big boy” funnel web (left).Credit: Kane Christensen

Finding the funnel web ‘heartland’

About 2018 Christensen, then the park’s head of spiders, drove his specimens down to the Australian Museum. The museum’s legendary spider guru, the late Dr Michael Gray, had long believed the Sydney funnel web was more than one species but struggled to prove it.

Christensen’s visit sparked an international team including Flinders University’s Dr Bruno Alves Buzatto to revisit the theory, and they got to work on the painstaking art of arachnid taxonomy.

The scientists dissected the sperm receptacles of females and scrutinised differences in their structure under microscopes. They also found the male’s embolus, a sperm-transferring needle that grows from the leg-like appendages beside a spider’s fangs called the pedipalps, was much longer and twisted in the “big boy” spiders.

Paired with two years of DNA analysis in Germany, these morphological findings confirmed Gray’s long-held suspicion. The famous Sydney funnel web was split into three species.

A normal male funnel web might grow a 2.5 centimetre body. A newly described species easily doubles that. (Note: do not handle funnel webs.)Credit: James Brickwood

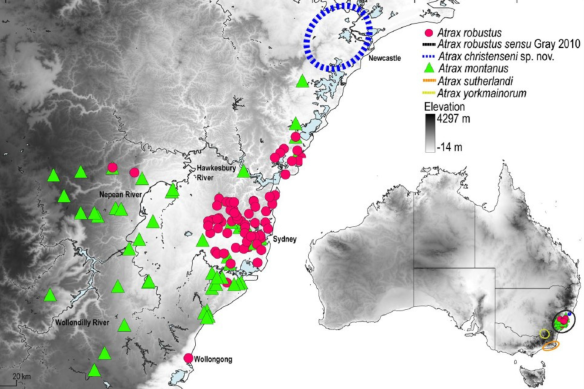

The “real” Sydney funnel web, Atrax robustus, calls the north shore and Central Coast home. “That’s the heartland,” Dr Helen Smith, an arachnologist at the museum and co-author of the BMC Ecology and Evolution study, said.

The second type, an almost identical but nonetheless different species dubbed the southern Sydney funnel web, was given a revived classification from the past: Atrax montanus.

“It does overlap with the Sydney funnel web, but it’s got a much wider distribution,” Smith said. “It goes a bit further north, much further west, into the upper Blue Mountains and further south past the Royal National Park.”

Then there’s the big boys.

“They’re actually a totally new species. They’re restricted to about 25 kilometres around Newcastle,” Smith said. “So we’re calling that the Newcastle funnel web.”

Distribution of classic Sydney funnel webs (pink dots), the wider-ranging southern Sydney funnel webs (green triangles) and the general location of Newcastle funnel webs (blue circle, exact locations obscured due to conservation fears).Credit: Loria et al, BMC Ecology and Evolution

Why the new species could be deadlier

Funnel-web bites normally occur during summer as males – six times more venomous to humans than females – emerge from silk-strewn burrows to seek mates. Their venom’s toxin, Delta-atracotoxin, induces muscle spasms, profuse sweating, tears, a rapid pulse and potential death within 15 minutes.

Recently an 11-month-old “miracle baby” born from a uterus transplant survived a bite on the finger from a funnel web which left him in a critical condition, the ABC reported in early December.

No one has died since the development of antivenom in 1981. Risk depends on how much venom a spider injects – often it’s none, known as a “dry bite”, said Professor Geoff Isbister, a clinical toxicologist at the University of Newcastle.

“For the Sydney funnel web, the rate of envenoming is about 10 to 20 per cent,” Isbister said. “But if you look at the southern and the northern tree funnel web, it’s about three in four [bites] that cause envenoming. And they’re much bigger spiders.

“So if you translate that to the Newcastle funnel web, yes, the biggest spiders are more likely to inject enough venom to cause envenoming. I suspect what they’re calling the ‘big boy’ is more likely to be dangerous.

“But the antivenom works for any funnel web, and this doesn’t change that.”

The fangs of a funnel web.Credit: Nick Moir

The unpublished secret

The funnel webs of the NSW coast diversified over millennia during cycles of dry and wet climates, Smith said. When the landscape dried out, the spiders probably retreated to isolated gullies, interbreeding in moist havens and becoming distinct species.

But like the wild grove of prehistoric Wollemi pines kept secret upon their discovery in 1994, the exact locations of the Newcastle funnel webs have been obscured from maps due to conservation fears.

“As soon as collectors get a whiff of a new species, there’s a huge trade in invertebrate specimens in Australia,” Smith said. “They could make quite a dent in the population.”

Despite the funnel web’s reputation as the boogeyman of backyard boots and a water-breathing killer haunting suburban pools, for Christensen it’s always been fascination over fear.

“I just love funnel webs so much,” he said. “Trying to add to the information we know about something that is nocturnal, that does like to hide, has always been my goal.

He never expected the day Dr Buzatto called to ask if they could name the species after him.

“That was, after my kids being born, one of my proudest days.”

The Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.

Read the full article here