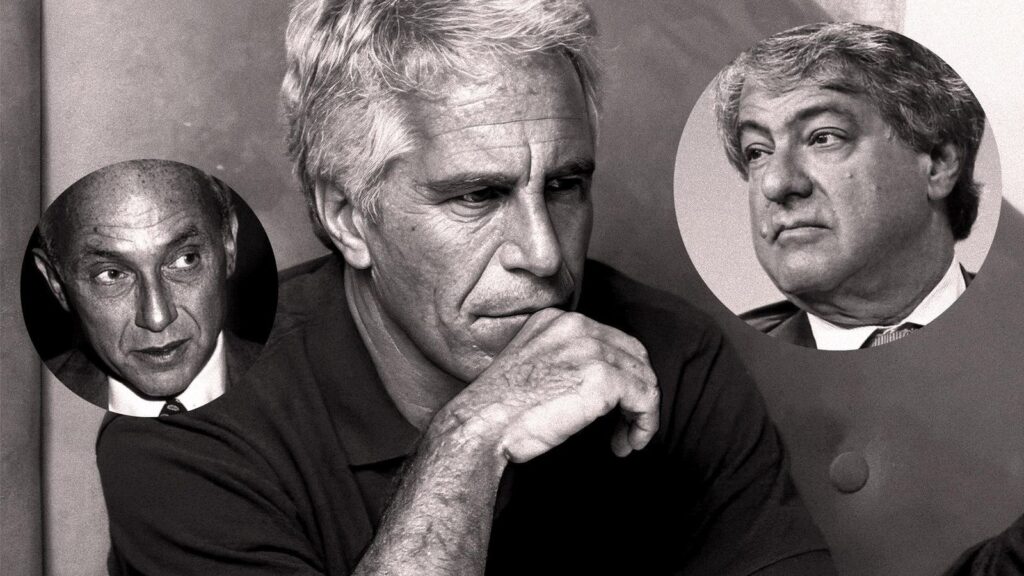

The convicted sex offender was worth nearly $600 million at his death, thanks mostly to two wealthy billionaire clients—plus generous tax breaks.

Atthe time of his death in 2019, Jeffrey Epstein was a fabulously wealthy man. Between his collection of lavish homes, two private Caribbean islands and nearly $380 million in cash and investments, he was worth $578 million, according to his estate.

Exactly how he accrued those riches is at the heart of the ongoing scandal. The less interesting possibility is that Epstein’s sex crimes were separate from his day job as a financial advisor to billionaires, to whom he offered investment, estate and tax planning services. In a 2013 corporate filing, Epstein described himself as “an experienced and successful financier and businessman,” an “entrepreneur who has built several highly profitable companies” and “one of the pioneers of derivative and option-based investing.” The more scandalous scenario, as alleged by many of President Donald Trump’s supporters and conspiracy theorists, is that Epstein secretly taped his wealthy friends engaging in sex crimes with trafficked minors in his homes and on his islands and then blackmailed them, with his financial business serving as cover.

The full origins of Epstein’s wealth remain shrouded in mystery, but what is clear, according to Forbes’ review of court filings, an investigative memo and financial records, is that Epstein relied above all on two billionaire clients and a tax gimmick to build his fortune.

Victoria’s Secret’s longtime chief Les Wexner and private equity honcho Leon Black were Epstein’s two largest financial clients. Of the more than $800 million in revenue Epstein’s two key businesses brought in from 1999 to 2018, according to financial statements obtained by a public records lawsuit filed by the New York Times, Epstein collected at least $490 million in fees, with the rest coming from gains on investments. Wexner and Black supplied upwards of 75% of Epstein’s fee income throughout that period, according to Forbes’ estimates. Those entities, both based in the U.S. Virgin Islands, were Epstein’s only “revenue-generating” companies from 1999 until his death, according to an expert report provided by an accountant in a 2022 case filed by the U.S. Virgin Islands government against JPMorgan Chase. While President Trump and Epstein were friends for many years, there is no evidence that they ever did any business together. They reportedly fell out after competing to buy the same Palm Beach estate in 2004; Trump won.

Wexner, 87, founder of apparel giant Limited, was Epstein’s primary client from 1991 until 2007 before the two men fell out and paid Epstein an estimated $200 million over the years. Black, 73, who founded private equity firm Apollo Global Management, paid Epstein $170 million between 2012 and 2017, according to an independent investigation from law firm Dechert LLP into Black’s relationship with Epstein and further research from the Senate Finance Committee.

Epstein was able to accumulate his wealth nearly tax-free thanks to generous tax breaks in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where he became a resident in 1996 and set up a financial consulting firm named Financial Trust Company two years later—the same year he spent nearly $8 million to buy Little St. James Island, which has since become known as “pedophile island” for its role in his sex trafficking ring. Court filings show that between that firm and Southern Trust Company, which he set up in 2011 and which took over as his main business the following year, Epstein obtained benefits under the territory’s economic development program that saved him $300 million in taxes between 1999 and 2018. Throughout that time, Epstein earned at least $360 million in dividends from his companies.

Wexner and Black have both apologized for their associations with Epstein and said they were not aware of his sex crimes. Wexner stepped down as CEO of L Brands in 2020 and said in a letter published that year that he “would not have continued to work with any individual capable of such egregious, sickening behavior” had he known. Black said in an earnings call in 2020 that he “deeply regretted” his association with Epstein; the Dechert report found “no evidence that Black…was involved in any way with Epstein’s criminal activities.” In 2021, he stepped down as Apollo CEO and from his position as chairman of the Museum of Modern Art. Spokespeople for Wexner and for Black declined to comment for this article.

The two men were not Epstein’s only clients. Johnson & Johnson heiress Elizabeth Johnson (d. 2017) was also a client, while billionaire Glenn Dubin’s hedge fund Highbridge Capital Management paid Epstein $15 million for introducing the firm to JPMorgan Chase, which acquired a majority stake in Highbridge for $1.3 billion in 2004. (Epstein raked in $127 million in revenues that year, his best ever, as his firm swelled to $476 million in net assets.) Epstein also worked with a former U.S. Treasury secretary, heads of state, Nobel laureates and prominent philanthropists, according to Black, who did not name any names. At one point, Epstein reportedly claimed to only work with people worth at least $1 billion. The only transactions between Epstein’s firms and his clients that have been made public are Leon Black’s $170 million in payments and Highbridge’s $15 million, as detailed in the Dechert investigation and the U.S. Virgin Islands government’s lawsuit against JPMorgan Chase.

It was Wexner, more than anyone, who laid the seeds of Epstein’s fortune. Born in 1937 in Dayton, Ohio, Wexner founded the retail company The Limited in 1963 and grew it into a billion-dollar business with popular brands like Victoria’s Secret and Bath and Body Works. Wexner met Epstein, a former Bear Stearns trader, through a mutual acquaintance in the 1980s. Enchanted by the charismatic man 15 years his junior, Wexner hired Epstein to help him manage his fortune. By 1991, Epstein held full power of attorney over Wexner’s finances.

It’s unclear exactly how much Wexner paid Epstein over the course of their relationship. Forbes estimates it was more than $200 million through 2007. Sources close to Wexner told the Wall Street Journal they believed it was “at least $200 million.”

That was just the cash. Epstein lived in Wexner’s 28,000-square-foot Manhattan townhouse for years before Wexner officially transferred the deed to the property to Epstein in 2011. (A person told the Journal that Epstein paid Wexner $20 million for the home in 1998 but there are no public records of that transaction. It was worth $56 million when he died in 2019.) Epstein paid $3.5 million for a home in Wexner’s planned community, New Albany, Ohio, in 1993 before flipping it for $8 million in 1998 to a company associated with Wexner. (It has the same mailing address as Wexner’s New Albany Company, where Epstein was also listed as a director in 1998.) One of Epstein’s jets, a Boeing 727 nicknamed the “Lolita Express,” was also owned by Wexner’s Limited from 1990 until 2001, when it was transferred to Epstein for an unknown amount.

The men fell out in 2007 after Epstein misappropriated at least $46 million from Wexner, the retail tycoon wrote in a 2020 letter. The end of Wexner’s patronage apparently dealt a huge blow to Epstein. From 2000 to 2006, Financial Trust Company, Epstein’s main business at that time, generated $300 million in fee income, according to its financial statements included in court records. Over the next six years, that business generated less than $5 million in fees.

Soon after Wexner severed ties with him, Epstein was hit by another blow: the 2008 financial crisis. From 2008 to 2012, Financial Trust recorded $166 million in net losses as Epstein reeled from the loss of his biggest client and tens of millions of dollars in sinking investments. His reputation was also damaged after he pleaded guilty in 2008 in Florida state court to two felony prostitution-related charges.

One man was pivotal in Epstein’s second act: Leon Black. The CEO and cofounder of private equity giant Apollo Global Management had known Epstein since the mid-1990s, and Epstein had served as a director of his Black Family Foundation from 1997 to 2007. In 2012, the two men started discussing the idea of Epstein advising Black on trust and estate planning, tax and philanthropic issues and the operations of Black’s family office. Black signed an agreement with Epstein’s Southern Trust Company, where Epstein would provide services in connection with “estate planning matters in respect of Mr. Black’s assets and estate,” in February 2013, according to the Dechert investigation.

Epstein told Black he usually charged his clients $40 million a year—a sum that seems improbable, considering Epstein had just established Southern Trust in 2011, and its predecessor, Financial Trust, had posted significant losses over the previous five years. Black wired $5.5 million to Southern Trust’s accounts at Deutsche Bank in 2012, according to a Senate Finance Committee investigation, but the payment doesn’t show up in the firm’s annual report for that year. In February 2013, Black and Epstein agreed to a $23.5 million payment for his services and negotiated a further $56.5 million three months later, paid out in installments, with Black paying Epstein a total of $50 million in 2013.

According to financial records, those payments from Black made up nearly all of the $51 million in fees that Southern Trust earned that year. The following year, Black agreed to pay Epstein for his services on an “ad hoc basis” without a written agreement. Black paid him $70 million in 2014 and $30 million in 2015 for his advice on estate and tax planning, audits, and managing his art collection, family office, yacht and airplane. Black’s payments made up the entirety of Southern Trust’s fee income in 2014 and more than half of its fee income in 2015. That same year, Black gave at least $10 million to a charity affiliated with Epstein.

Black doesn’t appear to have paid Epstein any money in 2016, and Southern Trust didn’t report any fee income for that year. In 2017, Black made his final payment to Epstein of $8 million—the only fees that Southern Trust reported receiving that year.

Taken together, the transactions reveal how Epstein was almost entirely dependent on Black for his income at the time. The $170 million is “an abnormal amount to pay for tax advice, yet no satisfactory explanation has been provided as to why Black paid Epstein such extraordinary sums without a written contract or agreement,” U.S. Senator Ron Wyden wrote in a letter to Attorney General Pam Bondi on Monday. (Black believed that Epstein had provided services that “conferred more than $1 billion and as much as $2 billion or more in value” to him, the Dechert report said.)

In 2017, Black also loaned $30.5 million to an Epstein company named Plan D, which owned a Gulfstream jet that Epstein allegedly used to transport young women and children to one of his islands, Little St. James. According to the Dechert report, the loans were intended to be short-term and “in connection with an art transaction involving Epstein.” Black demanded a full repayment in early 2018, but Epstein only repaid $10 million before his death in 2019. Black says he cut ties with Epstein in October 2018.

Aside from milking his two main patrons, Epstein relied on significant tax benefits from the U.S. Virgin Islands to build his wealth. The territory’s Economic Development Commission program, first established in the 1960s, provides a 90% exemption on corporate income tax and 100% on gross receipts and excise taxes—provided that a company employs at least 10 full-time U.S. Virgin Islands residents and invests $100,000 in a local business.

Epstein first applied for the benefits for Financial Trust in December 1998. The application was approved, granting him those tax benefits for 10 years through the end of 2009, which was later extended through 2014. (Court records showed that Epstein employed about 11 people at the firm at the time and invested $300,000 to meet the program’s requirements.) When he shifted his business to Southern Trust in 2012, he applied for the program through that firm and received approval in March 2013, granting it the same tax breaks until the end of 2023. Those benefits appear to have ended when he died in 2019.

Epstein’s tax savings were enormous. Thanks to the exemptions, his firms only paid about $41 million in taxes between 1999 and 2018, according to court filings. Forbes estimates Epstein only paid an average tax rate of about 3.9% on the firms’ revenues throughout that period. That’s compared to the top corporate income tax rate of 38.5% that the U.S. Virgin Islands charged throughout most of that period.

The territory’s government has since tried to claw some of that back. In a 2022 settlement with the U.S. Virgin Islands, the estate agreed to repay more than $80 million in economic development tax benefits that the government says were “fraudulently obtained to fuel his criminal enterprise.” Leon Black also settled a case with the U.S. Virgin Islands in connection to his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein for $62.5 million in 2023.

Six years after his death, Epstein’s estate is still flush with cash. It held $131 million in assets as of its latest quarterly report on March 31, including $49 million in cash and $79 million in unspecified “entities.” Over the past six years, the estate sold all of Epstein’s homes and islands and spent down much of its cash by distributing more than $160 million to victims, repaying a $30 million loan and agreeing to a $105 million settlement with the U.S. Virgin Islands. Yet it also got a boost last year when it received a $112 million tax refund from the IRS.

The full extent of Epstein’s wealth and client list is still unknown, though further details may be public soon enough. On July 17, Senator Ron Wyden revealed that investigators from the Senate Finance Committee had reviewed some of the Treasury Department’s files on Epstein last year. They found that there were more than 4,700 transactions with Epstein’s accounts at four banks—JPMorgan Chase, Deutsche Bank, Bank of New York Mellon and Bank of America—totaling more than $1.9 billion.

“I am convinced that the DOJ ignored evidence found in the U.S. Treasury Department’s Epstein file, a binder that contains extensive details on the mountains of cash Epstein received from prominent businessmen that Epstein used to finance his criminal network,” Wyden wrote in his letter to Attorney General Pam Bondi. “Epstein clearly had access to enormous financing to operate his sex trafficking network, and the details on how he got the cash to pay for it are sitting in a Treasury Department filing cabinet.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated on July 25 to cite a public records lawsuit filed by the New York Times that obtained Epstein’s financial statements in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Read the full article here