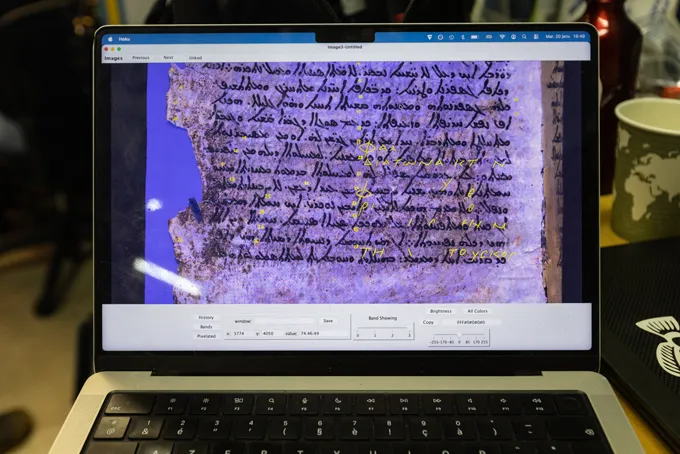

Surrounded by metal pipes and tangles of cables, two researchers point to bright orange squiggles on a computer screen. The squiggles are a poem written in ancient Greek about heavenly phenomena, seen for the first time by human eyes in nearly a millennium and a half.

“There’s an appendix which includes coordinates of the stars discussed in the poem, and then little sketches of the star maps,” says Minhal Gardezi, a physicist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Gardezi is part of a team working at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, Calif., to uncover these star maps. The maps originated in a catalog created by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus of Nicaea around 150 B.C. and were copied down sometime in the 6th century A.D. Transcribed onto animal hide, the poem and maps were later erased and overwritten with new text. By exposing the hide to powerful X-rays from SLAC’s particle accelerator, the invisible writing is once again revealed.

Direct knowledge from the ancient world is scarce. Most Greek scholars wrote on papyrus, a material that rarely survives the centuries. Almost none of Hipparchus’ writing has been found, though secondhand sources indicate that he created one of the earliest star catalogs and helped invent trigonometry. The copy at SLAC represents a treasure trove for researchers hoping to better understand the birth of science more than 2,000 years ago.

The document is around 18 by 21 centimeters, roughly the size of a paperback, and is known as a palimpsest, a piece of parchment made from goat or sheepskin whose original text was scraped off and then written over. This particular one, called the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, comes from Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai desert. Sometime in the 9th or 10th century, a scribe used the blank palimpsest — erased by either the monks or someone before them — to record monastic treatises.

While the expunged text is no longer visible to the naked eye, advanced imaging techniques had already partially revealed the hidden writing. This is possible because chemical residues from the ink used in the original document soaked into the parchment, subtly changing how the material absorbs light. By exposing these faint marks to different wavelengths of light — some within our visible range and others slightly beyond — portions of the erased text can be recovered.

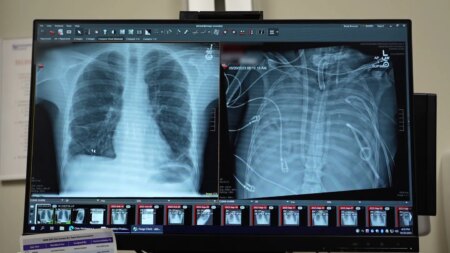

To get the full picture, researchers shone SLAC’s focused and intense X-rays, far beyond visible light and which can be a million times as strong as those used in a dentist’s office, on the manuscript, taking precautions to avoid damaging the material. The X-rays excite the ink’s chemical elements, causing them to fluoresce. “You don’t see them, but they’re still there,” says Uwe Bergmann, a physicist also at UW–Madison. The X-rays discerned calcium signals in the older, hidden writing that were more prominent than in the new.

The palimpsest’s first text was the poem “Phaenomena” by the Greek poet Aratus of Soli. Composed originally around 275 B.C., it describes the rising and setting of different constellations. Whoever copied down the poem onto the palimpsest — an unknown scribe from the 6th century — also included appendix-type sections that described the positions of stars in the constellations. The researchers know those sections came from Hipparchus because their precision and distinct coordinate system match later descriptions of his work.

Gardezi says it’s like an editor adding footnotes to a copy of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” that “gave us fun facts, like a recipe for food that was eaten in the play.”

Having recovered some snippets, the team now plans to scan the remaining palimpsests in the codex. Computer algorithms will help further enhance the writing and maps so that the team can glean more data from these scant squiggles. The advanced imaging has so far helped settle a long-standing debate about whether the Roman-Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy, who lived during the 2nd century A.D., plagiarized Hipparchus’ work. It turns out Ptolemy’s star catalogs used Hipparchus’ as a reference but also incorporated material from other scholars.

“That’s not plagiarism, that’s science,” says study coauthor Victor Gysembergh, a historian of science at CNRS in Paris. “We still do that today, combining sources to get the best data possible.”

Other researchers are looking forward to seeing what additional secrets the palimpsests might contain. Previous experiments from the team revealed descriptions of the foundations of calculus — generally believed to have been invented during the late 1600s — in a copy of Archimedes’ writings from the 3rd century B.C., says Graham George, a geologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada, who was not involved in the work.

“Who knows what the star chart study will show?” he asks. “I can’t wait to find out.”

Read the full article here