An ancient cradle of evolution may have been discovered in the striped cliffs of the Grand Canyon.

Paleontologists have found an exceptionally well-preserved trove of fossils in the greenish shales of the Bright Angel Formation. Today, these shales overlook the Colorado River from various points throughout the canyon, but they formed roughly half a billion years ago, during the Cambrian Period.

The fossilized fauna include sophisticated organisms like a newly identified species of penis worm with a retractable mouth, as well as mollusks and crustaceans that share similarities with modern animals, researchers report July 23 in Science Advances. The fossils paint a picture of a thriving ecosystem in which organisms developed increasingly complex features, resulting in a sort of evolutionary arms race.

“There are only some kinds of settings which can really launch evolutionary innovation forward,” says paleontologist Giovanni Mussini of the University of Cambridge. “And the Grand Canyon was probably one of them back in the Cambrian.”

Fossil evidence from around the world suggests that most modern animal groups first appeared during the early Cambrian Period, amid a biodiversity boom called the Cambrian Explosion. Many Cambrian fossils originated in locations once relatively far offshore that were oxygen-poor, which reduced decomposition and promoted preservation. But such sites, which include the famous Burgess Shale in the Canadian Rockies, may not tell the story of life in more habitable Cambrian ecosystems, Mussini says.

Half a billion years ago, much of western North America would have been inundated in a shallow sea. The types of sediments in the Bright Angel Formation suggest the layer formed on the ancient continental shelf at a depth of “at most, a couple dozen meters,” where sunlight could illuminate the seabed, Mussini says. “There was probably much more photosynthesis going on” compared with the Burgess Shale’s environment.

What’s more, the site would have probably been closer to deltas and estuaries that delivered nutrients into the ocean. And in contrast to the dark Burgess Shale, the light color of the Bright Angel formation suggests that much of the organic material was being recycled by a prolific fauna, Mussini says.

In 2023, he and colleagues spent weeks traveling downriver on a dinghy through the Grand Canyon, stopping at beaches to sample shales. Mussini was searching for small carbonaceous fossils, which can preserve in exquisite detail animal remains lacking bones or other hard parts.

Finding such fossils “is partly a game of luck,” Mussini says, as they’re too small to spot by eye. So after collecting dozens of shale samples from throughout the canyon, the researchers checked their bounty back in the lab by dissolving the samples in acid and picking through the residue under a microscope. In total, they recovered over 1,500 specimens, including “the first exceptionally preserved Cambrian animals from the Grand Canyon,” Mussini says.

The fauna include crustaceans with arrays of bristles that were probably used to capture food particles in the water column. These crustaceans “would have looked very similar to modern day brine shrimp … the kind of things that flamingos tend to eat,” Mussini says. And a mollusk had overlapping, blunt teeth that would have been good at scraping, much like a modern garden snail or sea slug.

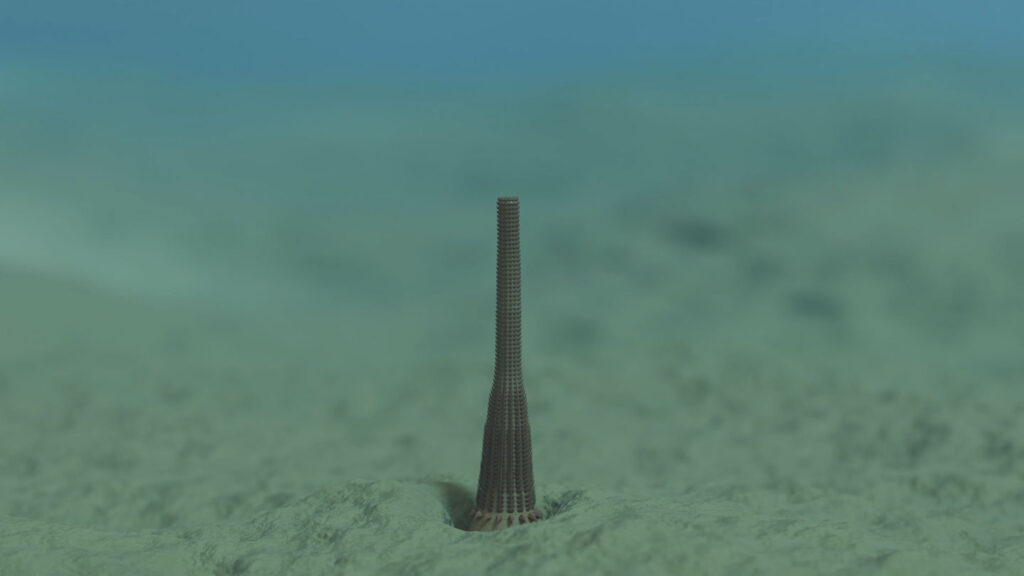

Then there’s the penis worm. While penis worms were already known to have existed at this time, this species has complex teeth with finely branching projections lining its pharynx, along with other robust and spiny teeth, which Mussini says “are much more complex than any of its counterparts from the Burgess Shale.”

The modern and sophisticated traits found in the Bright Angel biota suggest the environment was plentiful enough for competing species to invest in complex adaptations, Mussini says. These organisms may have then spread into settings like that of the Burgess Shale, where resources would have been more limited, he speculates.

“The data that they presented is consistent with that … [but] I don’t think the book is closed says paleontologist Karma Nanglu of the University of California, Riverside, who was not involved in the work. The biota of the Bright Angel Formation and the Burgess Shale are both quite biodiverse, so it’s not clear that one represents the source of traits found in the other, he says. If the researchers could find older fossils that show shallower environments were more biodiverse than deeper ones, that would make their case stronger, he says.

Mussini plans to continue searching for sophisticated specimens even older than the Cambrian Period. It’s “in the spirit of trying to see if some of these innovations are actually older than we thought,” he says. “This record is still relatively untapped.”

Read the full article here