NEW ORLEANS — One year ago, scientists made a surprisingly concrete prediction: Before 2025 was out, they said, Axial volcano — a submerged seamount near Oregon in the Northern Pacific Ocean — would erupt.

That hasn’t happened. But it still might — in 2026.

Scientists haven’t yet come up with a reliable way to forecast a volcanic eruption, particularly not months or years in advance. Last year, researchers hoped they’d identified the right pattern of data to anticipate Axial’s eruption. Now, they’re turning back to the data to hunt for more clues.

A combined analysis of seismic and seafloor inflation data around Axial seamount could offer a way to forecast future eruptions, says geophysicist William Chadwick of Oregon State University’s Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport. His new analysis kicks the can just a bit down the road, suggesting an eruption could happen sometime in 2026.

Chadwick reported these findings December 16 at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting, a follow-up of sorts to his prediction at last year’s meeting that Axial would erupt in 2025. In the new study, he analyzed why that prediction might have been premature, and considered new avenues for researchers to consider when it comes to eruption forecasting.

“This whole thing’s been an experiment to see how far we can push the envelope of long-term [eruption] forecasting,” he says. And part of that “is learning from experience what’s possible and what’s not possible.”

The previous prediction was based on a repeated and apparently intensifying pattern of seafloor inflation and deflation, linked to the movement of magma underground. It was a pattern the team had also seen in 2015 — and used to successfully predict that Axial would erupt that year.

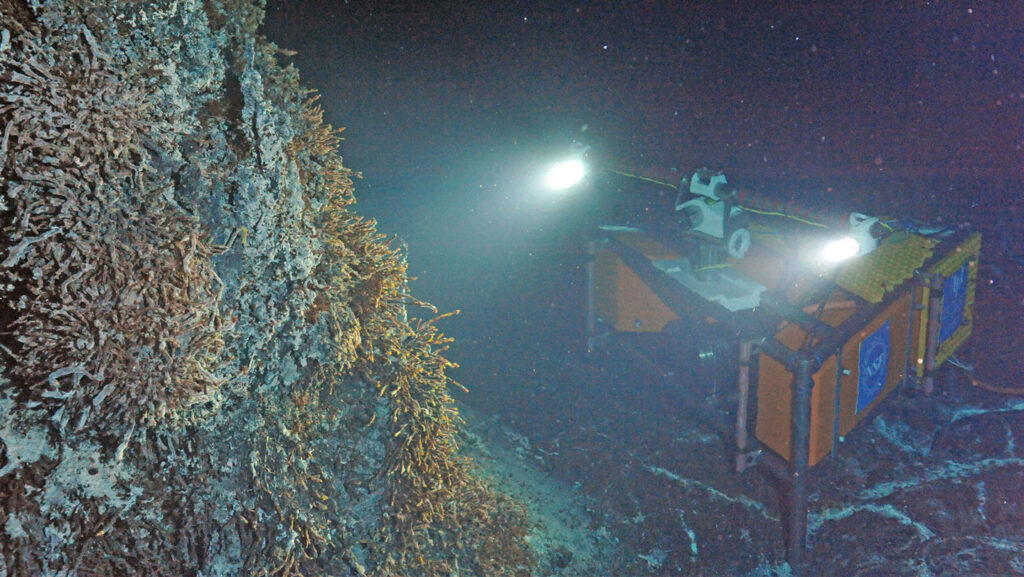

Axial seamount — about 480 kilometers off the coast of Oregon and buried beneath the waves — is an excellent test laboratory: It erupts frequently, is peppered with the most instrumentation of any underwater volcano and poses no danger to anybody. And that may be exactly what researchers need if they’re going to determine how and when a volcano’s rumbles and fidgets presage an actual eruption.

Axial’s every rumble and sigh has been logged with underwater sensors since 1997. And since 2014, a network of submarine fiber-optic cables, bearing an array of 150 instruments, has been delivering data in real time as the ground shakes or the seafloor around Axial swells or shrinks — both signs of magma on the move. That cabled network, part of the National Science Foundation’s Ocean Observatories Initiative, or OOI, spans the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate, a chunk of oceanic crust off the northwest U.S. coast.

But 2025 has come and gone, Axial has already swelled higher than it did in 2015, and it’s now clear that that pattern of inflation and deflation alone isn’t reliable enough to base a forecast on. The pattern isn’t quite regular enough, and there isn’t a clear threshold that triggers an eruption.

“Every time we try to anticipate when we’re going to get up to that threshold, something changes and we’re wrong,” Chadwick says. “In retrospect, we got lucky in 2015.”

So now what, when it comes to eruption forecasting? One possibility is to look for a telltale pattern by analyzing the seafloor deformation and seismic data at the same time.

For example, before the 2015 eruption, the OOI recorded a dramatic increase in quake activity as the ground also swelled upward. For several months, there were about 10,000 quakes per centimeter of seafloor inflation; the inflation was also rapid, rising at a rate of 70 centimeters per year. In 2024, scientists saw a brief period of similarly intense quake activity, but it didn’t last. Inflation rates were also much lower, about 15 to 25 centimeters per year.

Assuming the 2015 data represent an eruption threshold, Chadwick said at the meeting, “we hypothesize that we need to get to 500 earthquakes a day before the next eruption is triggered.” Based on current rates of inflation and seismicity, that threshold could come sometime in 2026.

Other researchers are exploring eruption forecasting based on physics — specifically, anticipating how and when geologic structures might reach a point of failure. Geophysicists Qinghua Lei of Uppsala University in Sweden and Didier Sornette of ETH Zurich have previously developed a physics-based computer model designed to predict moments of geological failure, such as the slumping of a landslide or the release of a burst of lava. Given existing monitoring data, they were able to retrospectively predict several natural hazard events. The trick now is to figure it out ahead of time.

In November, Lei and Sornette started a new project that takes the real-time OOI cable data and feeds it into their computer model. Based on these data, the researchers plan to create monthly prototype eruption forecasts for Axial. As the project is still in its experimental stage, they won’t release these forecasts to the public until after the next eruption.

The success of these eruption prediction efforts at Axial hinges on the continued supply of data from the OOI — and it’s not clear how long the array will be able to operate. The Trump administration has proposed an 80 percent cut to the program, which is funded through NSF. Those and other cuts to the country’s scientific agencies are in limbo through January.

“It’s been a bit of a challenging year for us, and for many people in the sciences, but we’re still alive and kicking,” says OOI principal investigator James Edson, a physical oceanographer with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. Working with NSF, the OOI managed to garner enough support to keep the array running through the summer of 2026, he told researchers at an AGU assembly to discuss Axial.

Although Axial’s status remained largely unchanged throughout 2025, news stories about the 2025 eruption prediction continued to bubble up throughout the year. “I’ve been amazed, because we’ve been doing this for years, but the interest has really exploded this last year,” Chadwick says. Some of the stories have dramatically exaggerated the danger the volcano poses. “Several times I’ve gotten emails from random people who live on the Oregon coast who are worried.”

If the new predictions prove true, he may need to brace for more emails.

Read the full article here