Scientists have gotten their closest-ever view of the denizens that inhabit a frigid underworld.

An analysis of the genetic blueprints of nearly 1,400 microbes sampled from one buried Antarctic lake reveals that these single-celled creatures have surprisingly flexible metabolisms and are evolutionarily distant from any other known microbes, researchers report August 18 in Nature Communications.

Dotted with subglacial rivers and lakes, West Antarctica is three times the size of Texas, smothered under a kilometer or more of glacial ice. This cold, dark landscape “is a massive area of our planet [where] we have no idea what is going on,” says Alexander Michaud, a polar microbiologist at the Ohio State University in Columbus, who was not part of the study. This new work, he says, provides “an unprecedented, detailed look into who’s living there and how they’re doing it.”

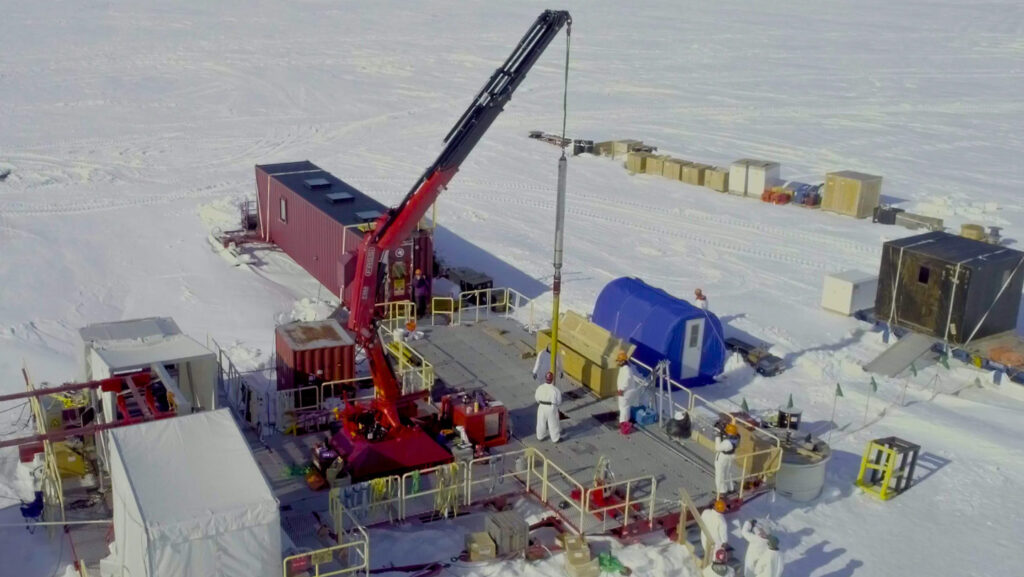

Scientists have sampled liquid water and mud from only two of the more than 600 subglacial lakes known in Antarctica. The first time, in 2013, a team from the United States drilled through 800 meters of glacial ice and retrieved samples from Lake Whillans in West Antarctica.

Each milliliter of the lake’s water contained 130,000 living cells. Using a “DNA barcoding” technique, the U.S. team analyzed a single gene across the samples and found that microbes in the lake generally belonged to groups that were well-known from other parts of the world. At the time, it was a major advance.

But when U.S. researchers drilled into another subglacial body of water called Lake Mercer in 2018, they had collaborators ready to study the lake’s microbes using a more advanced technique called single-cell whole genome amplification.

For the new study, scientists with the Korea Polar Research Institute in Incheon isolated 1,374 microbial cells and pieced together each organism’s genome. Analyses of the genomes revealed a major surprise: Microbes that had seemed familiar based on single-gene barcoding suddenly looked a lot more unique when their entire genome was unveiled.

That ended a long-held speculation that maybe these microbes had gotten into the lakes when seawater intruded under the ice sheet only 6,000 years ago. Instead, the data show the microbes had to have been living there a lot longer.

“They are specialists” for living under glaciers, says Kyuin Hwang, a bioinformaticist at the Korea Polar Research Institute who analyzed the genomes. “They may have adapted to this condition for a very long time.”

They probably evolved from microbes inhabiting Antarctica’s land, possibly living under ice ever since glaciers began to expand on the continent, roughly 30 million years ago.

The new genomes also produced another surprise: These microbes were the bacterial equivalent of Swiss Army knives. Many of them could grow with or without oxygen. Many could alternate between eating organic carbon such as dead cells and absorbing carbon dioxide to manufacture their own food the way plants do. But rather than using sunlight to power their CO2 absorption, they used other metabolic pathways as energy sources, often oxidizing iron or sulfur from crushed minerals.

“This versatility is what allows them to survive” under the ice, says Hanbyul Lee, a microbial ecologist also at the Korea Polar Research Institute.

It’s a harsh environment with very little for the critters to gnaw on other than crushed rocks, says Brent Christner, a polar microbiologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville, who was involved in sampling both Lake Whillans and Lake Mercer. “These microbes, on a good year, maybe divide twice a year,” he says.

The amount of oxygen-laden water that flows into these lakes from rivers upstream also fluctuates, he says. “It’s probably really common that these lakes run out of oxygen.”

Christner believes that the microbes living in Lake Mercer are probably washed there from parts of the continent that are farther inland — places that are far more isolated from the outside world, with even less to eat. By Antarctic standards, Lakes Mercer and Whillans might be pretty cushy places, he says. “They’re probably the rain forests of Antarctica.”

Read the full article here