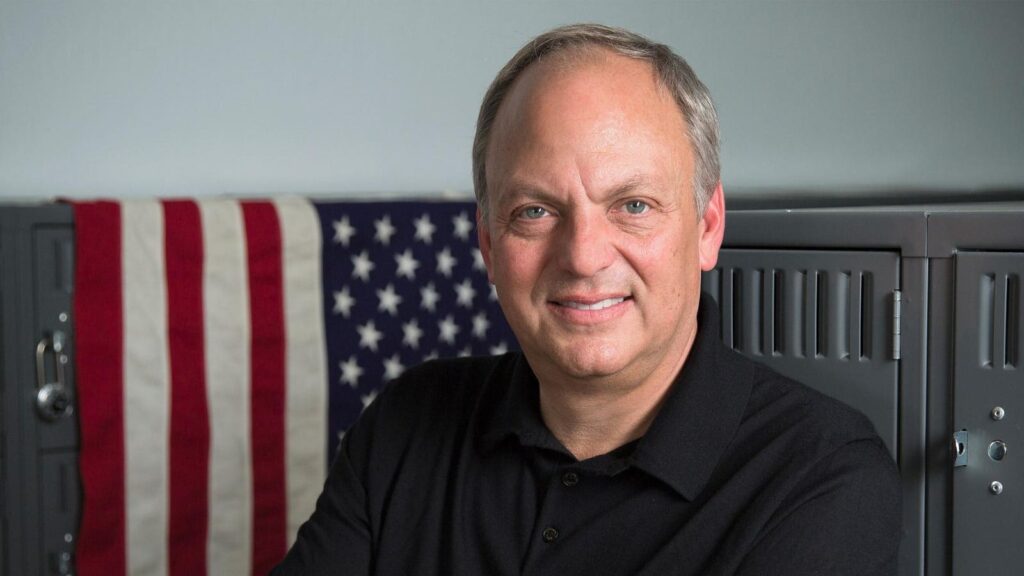

On a December phone call with Forbes, the founder of the $800 million (revenue) private company WeatherTech, David MacNeil, ranted about product labels. “If you walk into any store in America and you pick up a box, the Federal Trade Commission requires everything that you purchase to have a country of origin. But when you go online, there’s no regulation for that,” he vented. “The American consumers are being deceived and cheated by not knowing where the product is being made. This is a serious, serious situation that needs to be rectified either by executive order, or by Congress.” Or, he added: “yet-to-be-created FTC guidelines.”

No matter that his diatribe included some hyperbole—the rules mandating country of origin labels for products are complex and don’t apply across the board, according to the FTC and CBP. This patriotic rhetoric plays well in certain circles these days.

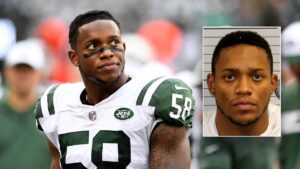

Just a few weeks after his conversation with Forbes, President Trump nominated MacNeil—a member at Mar-a-Lago who has donated over $3 million to Trump’s campaigns, associated PACs and inaugurations—to fill one of three open spots on the FTC. If approved, MacNeil, who Forbes estimates is worth more than $4 billion, will become the 12th known billionaire or billionaire’s spouse currently in Trump’s government.

“I’m ready to roll up my sleeves and go to work to help every consumer in America,” MacNeil, 66, tells Forbes. He’s also undoubtedly ready, if confirmed, to use the office to further one of his biggest ambitions: promoting American manufacturing. New FTC “country of origin” rules would be a start.

MacNeil was championing domestic manufacturing long before it was cool. He started selling some U.S.-made merchandise in 1994, five years after founding the business and the same year that NAFTA took effect, ushering in an era of lower tariffs and rabid offshoring. He gradually ramped up from there, and today, WeatherTech makes all of its products in 11 factory facilities in Illinois and sources all of its materials within the United States. “We are so vertically integrated, we cook our own food for the employees. We cut our own lawns,” says MacNeil. “We extrude our own plastic. We design, engineer, and manufacture our own molds and tooling.”

He’s touted WeatherTech’s U.S. production on billboards, in Super Bowl ads and even at a donor lunch with Trump before he was elected. Seated next to the future president, MacNeil says Trump baited him. “‘David, you could make so much more money by manufacturing your products in China. Why don’t you just make them in China?’” MacNeil recalls him asking. “I said, ‘It’s more important to provide jobs to my fellow Americans than it is to make another buck supporting Chinese manufacturing.’ He really liked that answer.”

Trump’s second-term tariffs have already helped WeatherTech relative to some rivals. “Tariffs are certainly taking a toll in the automotive space,” says Dan Daitchman, managing director at financial advisory firm GA Group. While the taxes have mainly targeted cars and car components, he explains, so-called “aftermarket” parts and accessories like those sold by WeatherTech have also been hit, with that industry’s gross margins squeezed up to 4% in the first half of 2025. WeatherTech’s margins are also down slightly, but by more like 2%, and MacNeil says that’s due to inflationary pressures and the rising cost of the oil in its plastic. Retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports are also less of an issue for WeatherTech because roughly 95% of its sales are within the United States. Claims MacNeil, “WeatherTech is getting a larger slice of a shrinking pie.”

Which, in turn, is revving up his own fortune. Based on Forbes estimates, WeatherTech, which he owns outright, is worth $2.4 billion. MacNeil also has at least $320 million in personal real estate—most in Florida, where he began relocating in 2016—including an estimated $27 million estate for his daughter in Wellington and $75 million mansion he just bought in Manalapan, both near Palm Beach. Then there’s his collection of about 350 cars worth in excess of $400 million (MacNeil says it’s more like $500 million) and $90 million in a set of jets, planes and helicopters that he largely flies himself. (Flying is his “real passion,” he says.) Plus other assets, like commercial real estate in Illinois and Florida that he rents to small businesses such as a brewery, a window tinter and a pizza joint.

Many of his investments were funded with profits from WeatherTech. Tax filings leaked to ProPublica in 2020 showed that MacNeil has compensated himself generously at times, collecting roughly $180 million between 2016 and 2018. While he declines to share his recent salaries (and says he began lowering them substantially to reinvest more into the business in 2019), he says that he and WeatherTech have paid “well over” $500 million in taxes in the past decade.

MacNeil, who has a knack for turning any conversation into a passionate argument for American manufacturing, insists WeatherTech’s success is not just good for him, but for the country.

“We have to maintain our industrial might,” he interjects while explaining WeatherTech’s pricing. “If we don’t have the ability to manufacture things, we’re lost as a society. We’ve become a country of services—people cutting lawns and cutting hair.”

It’s sometimes said that the fiercest patriots are naturalized citizens. That’s certainly true of MacNeil, who was born in Canada in 1959 but immigrated to the Chicago suburbs on a green card when he was less than a year old. He was raised by his mom, who taught pediatric nursing at the University of Illinois.

She also taught him about hard work. “I don’t even know if I could spell ‘entrepreneurial spirit’ as I was growing up, let alone know what it was,” recalls MacNeil. “What I did have was a work ethic to do a great job at whatever I applied myself to.” His first job in high school was pumping gas for $3 an hour. Soon he was driving taxis and limos (he was once a driver for the late radio broadcaster Paul Harvey) and working as a machinist and car salesman. He eventually secured a VP of sales role at auto engineering firm AMG and later opened his own classic car dealership.

Cars were clearly the theme. “I grew up in the heyday of muscle cars for America. The cool kids always had a cool car,” says MacNeil. He bought his first vehicle—and his family’s first—in 1976 for $300 (the equivalent of about $1,700 today): a two-door 1968 Chevy Impala with a fried engine, which he replaced with a working one he got in a junkyard for $100. He started racing cars in college and is a bronze-rated FIA driver. (His youngest son, Cooper, is a retired professional racer; he and his two siblings work at WeatherTech).

It was on a 1989 trip to Scotland that MacNeil first got the idea for WeatherTech. Encountering some bad weather, he noticed that the mats in his rental car had ridges to prevent runoff from mud and snow. It was unlike anything he’d seen back home. He made note of the brand, returned the vehicle and continued his travels, but couldn’t stop thinking about them.

“My wife looked at me like I was crazy, because I’m talking about these rubber floor mats,” he remembers. “And I’m like, ‘People could use these in America.’”

Back home a week later, he called up the company—Cannon Rubber, a since-dissolved UK firm—and convinced them to make him their North American distributor. Cannon required that he pay for the mats up front, so he took out a $50,000 second mortgage on his house to buy a 20-foot container’s worth. Luckily, the demand was there: He sold $30,000 in mats that first month, largely by driving around and pitching local dealerships and placing an ad in Road & Track magazine. Within two years, the business was profitable.

The partnership unraveled in 2007 over what MacNeil alleged were defective mats. Later that year, he ditched Cannon to start making mats himself, at first with the help of a contract manufacturer.

Next was building up his own brand. “We did some focus groups, and one of the things that we learned was that when somebody buys a new car, anything that happens in that new car is a tragic event,” says Dave Sollitt, former strategic planning executive at Pinnacle, WeatherTech’s TV ad firm at the time. “A new car is somebody’s biggest single investment other than a house.” So the company’s first three television commercials, together made for just $50,000, showed drivers beset by messes, from a spilled coffee to a dog (played by one of MacNeil’s golden retrievers) tracking in mud. WeatherTech’s sales went up some 250% after a month in the initial four markets where they aired.

In 2014, MacNeil gambled $4 million on the company’s first Super Bowl ad. “If you’re going to become a household name, you need to be in every household,” he says.

After another few years, MacNeil began to move beyond auto products. Soon WeatherTech was selling indoor mats for kitchens and bathrooms, boot trays, coasters, tablet holders and even stainless steel pet bowls. “We try to solve problems with products,” he says, explaining that he designed the latter after some pet feeders made abroad (like those targeted in a 2012 Petco recall) were found to contain trace radioactive material.

These days, the brand drops over $100 million a year on marketing, including billboards that plaster the highways of his hometown of Chicago—its outdoor ad spending in the city is the sixth-highest among Illinois-based companies, according to MediaRadar—and an average of $8 million on its now-annual Super Bowl ads, typically featuring Americana imagery and messaging, and yes, his dogs.

Research firm Brand Keys ranked WeatherTech as the 24th most patriotic brand in the country last year. “They’ve done a genius job telling the brand story,” says industry sales and marketing veteran Peter MacGillivray, noting that WeatherTech is unique among its competitors for appealing to both gearheads and average drivers. “They’ve emerged into the mainstream.”

Of course, being all-American comes with a (literally) steep price. WeatherTech is known for being expensive: Drivers of a new Ford F-150, the most popular car in the country, must pay $140 for its premium FloorLiner HP mat.

“When you really understand what went into that product, it’s a bargain,” says MacNeil, pointing to the laser-measured, injection mold engineering, the rubber-like polymer that’s high-quality and odorless, and the “real wages” he pays his workers (compared to his Chinese counterparts, he says), which start at about $22 an hour for entry-level jobs and $30 to $35 for skilled jobs. “There’s nothing cheap about what we do, but there is excellence.” Industry vet MacGillivray agrees, calling WeatherTech products “the gold standard.”

These days, MacNeil has been merging into new lanes. One is politics. In 2018, he spoke out publicly in support of DACA, which protects undocumented people who immigrated to the U.S. as kids from deportation, announcing he was withholding donations to Republican politicians who didn’t support the program. “It’s so emotional to me because I was an immigrant myself,” he says. MacNeil declines to share specific thoughts on Trump’s current immigration policies, offering only: “Immigration laws must be rationally and compassionately enforced until Congress says and legislates otherwise. Clearly our laws cannot be selectively enforced.”

And for at least the past year, he’s been publicly lobbying for those “yet-to-be-created FTC guidelines” requiring online goods to show where they’re made.

Evidently the president heard the call. Trump’s nomination of MacNeil could put him in the position to turn his advocacy into action. The FTC is one of the most high-profile government agencies; with a mandate to protect consumers from unfair and anticompetitive business practices, it can regulate and police nearly any industry. (In May, the president had nominated him to be Ambassador at Large for Industrial and Manufacturing Competitiveness—a relatively tiny role—but his selection expired at the beginning of the year because the Senate failed to call a vote in time.)

Of course, this raises the question of conflicts of interest. The passage of his desired FTC guidelines would clearly benefit the all-American WeatherTech. The commission can also prosecute companies (including MacNeil’s competitors) that falsely claim to have U.S. origins, as it did when it fined Williams-Sonoma $3.17 million in 2024. Resources are limited, so any law enforcement priority comes at the expense of others.

“It’s not entirely clear where the lines are drawn, but if you’ve been actively lobbying for a particular rule change in the government, it does not look good to go into the government and vote as a commissioner on the same rule. It just looks like you’re not impartial,” says Richard Painter, who was an ethics lawyer at the White House under President George W. Bush.

“I’d say that 97% of the business before the Federal Trade Commission isn’t going to have a direct and predictable effect on WeatherTech,” he continues. “I do think he ought to stay away from anything involving that made-in-America business if he’s been lobbying on it. And that could be an issue if President Trump’s really trying to use the Federal Trade Commission to shift toward a very nationalistic, protectionist policy.”

There are ways to mitigate the appearance or existence of bias. More commonly, political appointees can recuse themselves from certain votes. Less commonly, says Painter, they can put their implicated assets into a blind trust—which doesn’t really work with a privately-held business—or sell them.

MacNeil isn’t concerned: “I won’t do anything that won’t benefit all people. I have no allegiance to anyone but the American people.” He already expects to step back from day-to-day operations at WeatherTech if confirmed. “If I get within a thousand miles of a conflict of interest, I’m going to recuse myself and go to the government lawyers, or my superiors, and ask for advice on how to handle the situation,” he says. “But God forbid WeatherTech gets swept up in a big group of all the other American manufacturers across our great nation. We all benefit from better laws and better disclosures to all consumers—I don’t feel that’s a conflict of interest.”

He’s already been entertaining offers for WeatherTech, though he hasn’t been actively trying to sell it. “I always say everything’s for sale except my dogs, daughter and wife,” he quips (his two sons are evidently fair game). In order to part with the company, he says he’d need to be sure that the buyer was committed to continuing its “excellence and customer-centric philosophy.”

For MacNeil, that’s an issue for the future. This week, at least, he’s just starting the paperwork needed ahead of the Senate confirmation process and enjoying the moment.

“Please Google ‘David MacNeil FTC,’” he emailed Forbes right after the news of Trump’s nomination broke. “Please be seated before you hit enter.”

Read the full article here