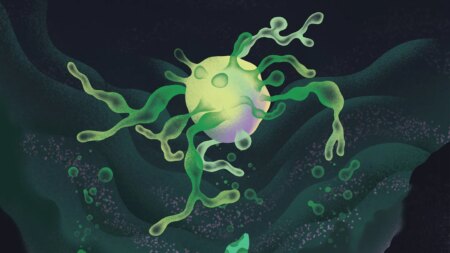

Small, icy moons might be boiling under their surface.

Many moons in the outer solar system are thought to harbor subsurface oceans beneath their icy crusts. New computer simulations, reported November 24 in Nature Astronomy, suggest that changes in the thickness of these icy shells can cause water in the underlying oceans to boil at low temperatures. This boiling may lead to geologic features, such as the ridgelike formations called coronae seen on Uranus’ moon Miranda.

“The idea that a subsurface ocean on an icy world could actually reach boiling conditions is a really remarkable scenario,” says Max Rudolph, a planetary geophysicist at the University of California, Davis.

Moons are constantly squeezed by their planet’s gravity, which generates heat. The amount of heating can change over time as a moon’s orbit changes, a common occurrence in multimoon systems, where satellites play gravitational tug-of-war as they pass one another.

In the new study, Rudolph and his colleagues calculated what would happen when the heating increases. They found that in some cases, a moon’s icy shell will melt from underneath. As the shell thins, the pressure on the ocean below decreases. On small moons, this pressure drop can cause the water below to reach its triple point, where ice, liquid and vapor coexist. In the subsurface oceans of icy moons, this happens around zero degrees Celsius — allowing the frigid ocean to boil.

The gases released as the ocean boils might create cracks in the ice shell, potentially forming surface features visible from space, as seen on Miranda. However, if the ice shell is thick enough, these cracks might not appear. This might explain the geologic calm observed on Saturn’s moon Mimas, another satellite thought to have a subsurface ocean.

“The overlying ice shell thickening and thinning over time might provide a means to explain how water could get through the ice shell from the ocean beneath to the surface,” says Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved with the study. He says the release of gases from an ocean can help explain why icy moons look the way they do.

However, not all are convinced. Planetary scientist Bill McKinnon, also at Washington University, thinks it’s important to study the effects of melting. But he doesn’t agree that such large-scale ocean boiling conditions would be reached in small moons, citing in part a differing view of geologic evidence, such as the lack of features on Mimas.

While the boiling of small moons is debated, larger moons almost certainly wouldn’t boil. Rudolph’s team found only worlds smaller than about 600 kilometers across can have boiling oceans. That’s because for larger bodies with higher gravity, such as Uranus’ moon Titania, stresses on the icy surface would cause it to crack before the ocean reached its triple point. This cracking, Rudolph says, may account for features seen in images taken by the Voyager 2 spacecraft as it flew by Titania in 1986.

Beyond enhancing our understanding of small moons’ geology, the findings may also inform the search for habitable conditions in the solar system.

“Looking at when these landforms developed … could tell you something about when the ocean developed,” Rudolph says. “And knowing that these icy worlds possess or have possessed a subsurface ocean through much of their geologic histories is really important in terms of thinking about the potential of those worlds to host life-forms.”

Read the full article here