Geopolitical tensions and conflicts, such as those in Ukraine, made the EU realise how vulnerable it is in relying on just one or even a few countries for key resources.

As was the case with Russian gas, the same logic applies to these so-called critical materials, natural resources that are essential to the economy.

The EU now wants to be more self-sufficient, boosting its domestic raw material capacity and diversifying supply sources. But how and at what price? That’s the focus of this episode of Europeans’ Stories.

The European Union needs critical raw materials for its Green Deal climate neutral goals – the Digital transition, security and defence, and space and innovation industries.

The EU has identified 34 critical raw materials, including lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements and magnesium.

But many have high-risk supply chains. For example, 63% of the world’s cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo and 100% of the rare earths used for permanent magnets are refined in China.

In 2024, the EU passed the Critical Raw Materials Act to boost domestic strategic raw material capacity.

The Act says that by 2030 Europe must mine 10% of annual EU needs, process 40% and recycle 25%. No more than 65% of annual EU needs for each strategic raw material should come from a single third country.

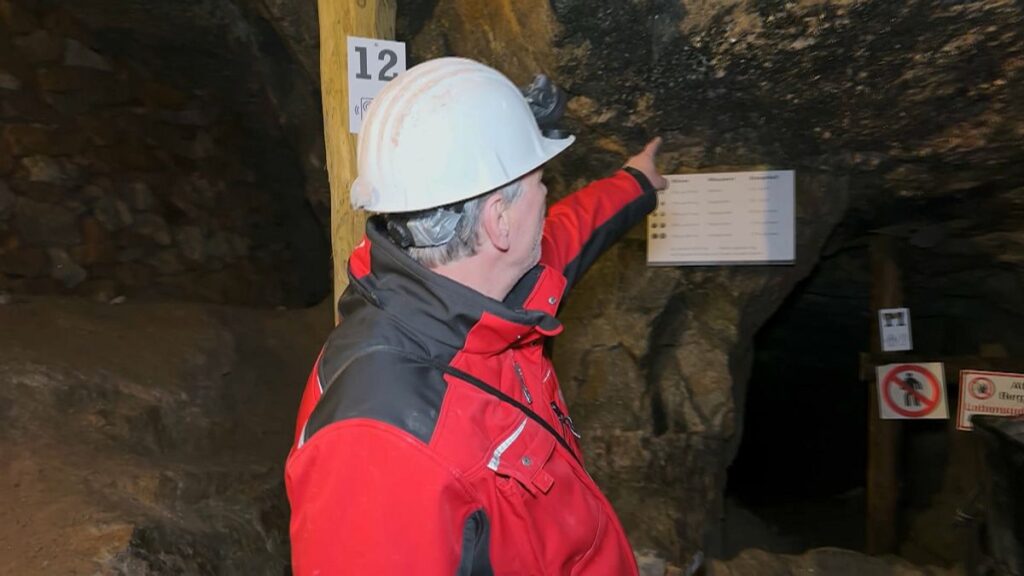

Mining is deeply embedded in the history of the Ore Mountains, stretching along the Czech-German border. Here, tin and tungsten reserves were exploited from the Middle Ages through to the 1990s, when they became unprofitable. Today, only a museum remains, but the energy transition is opening up new possibilities.

Lithium is a crucial element for battery production, and experts estimate that between three and five percent of the world’s lithium reserves can be found under the Czech town of Cínovec.

Geomet, a private company with state participation, is working to create what it says will be an environmentally friendly production chain. It’s one of the 47 Strategic Projects selected by the European Commission to boost domestic strategic raw material capacity.

“We’re going to mine almost 3 million tonnes of the ore per year and we will produce about 30,000 tonnes of final product per year,” says Tomáš Vrbický, a geologist who works for Geomet.

The company plans to not just mine the ore but also to produce lithium carbonate, a key ingredient used in the battery industry. It’s rare for a company to finalise the whole process internally, without resorting to third countries. But there will be many challenges and it’ll cost more.

How realistic are Europe’s plans?

By 2030 Europe aims to mine 10% of its annual needs, process 40% and recycle 25%.

Starý Jaromír, Head of Department from the Czech Geological Survey, doubts these targets could be met in such a short time.

“This objective is not realistic, because some of the European Union’s critical raw materials are not found on the European continent and are not currently mined. At present it is impossible to say that some of the critical raw materials will be handled in quantities of up to 10% of European consumption.”

When asked if the need for critical raw materials is making Europe forget the pollution that comes with mining, geologist Gabriel Zbyněk from the Czech Geological Survey replied that mining methods, as well as European legislation, have progressed concerning how mining is supervised and controlled today, and adds: “In the EU we really need these raw materials. And it’s probably a little hypocritical to say we don’t need any mining here, and if it’s going to be mined anywhere else in the world and in a way we don’t care about. Especially when it’s not ‘in our backyard’”.

All mineral extraction involves a degree of pollution. It may not be entirely avoidable, but it can be minimised. Europe’s challenge is finding the right balance between the need for a less polluting and socially fair industry, and the higher costs that this entails.

Read the full article here