Chris Buck stands barefoot in his kitchen holding a glass bottle of unfiltered Lithuanian farmhouse ale. He swirls the bottle gently to stir up a fingerbreadth blanket of yeast and pours the turbulent beer into a glass mug.

Buck raises the mug and sips. “Cloudy beer. Delightful!”

He has just consumed what may be the world’s first vaccine delivered in a beer. It could be the first small sip toward making vaccines more palatable and accessible to people around the world. Or it could fuel concerns about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Or the idea may go nowhere. No matter the outcome, the story of Buck’s unconventional approach illustrates the legal, ethical, moral, scientific and social challenges involved in developing potentially life-saving vaccines.

Buck isn’t just a home brewer dabbling in drug-making. He is a virologist at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., where he studies polyomaviruses, which have been linked to various cancers and to serious health problems for people with weakened immune systems. He discovered four of the 13 polyomaviruses known to infect humans.

The vaccine beer experiment grew out of research Buck and colleagues have been doing to develop a traditional vaccine against polyomavirus. But Buck’s experimental sips of vaccine beer are unsanctioned by his employer. A research ethics committee at the National Institutes of Health told Buck he couldn’t experiment on himself by drinking the beer.

Buck says the committee has the right to determine what he can and can’t do at work but can’t govern what he does in his private life. So today he is Chef Gusteau, the founder and sole employee of Gusteau Research Corporation, a nonprofit organization Buck established so he could make and drink his vaccine beer as a private citizen. His company’s name was inspired by the chef in the film Ratatouille, Auguste Gusteau, whose motto is “Anyone can cook.”

Buck’s body made antibodies against several types of the virus after drinking the beer and he suffered no ill effects, he and his brother Andrew Buck reported December 17 at the data sharing platform Zenodo.org, along with colleagues from NIH and Vilnius University in Lithuania. Andrew and other family members have also consumed the beer with no ill effects, he says. The Buck brothers posted a method for making vaccine beer December 17 at Zenodo.org. Chris Buck announced both publications in his blog Viruses Must Die on the online publishing platform Substack, but neither has been peer-reviewed by other scientists.

A second ethics committee at the NIH objected to Buck posting the manuscripts to the preprint server bioRxiv.org because of the self-experiment. Buck wrote a rebuttal to the committee’s comments but was loathe to wait for its blessing before sharing the data. “The bureaucracy is inhibiting the science, and that’s unacceptable to me,” he says. “One week of people dying from not knowing about this is not trivial.”

Buck’s unconventional approach has also sparked concerns among other experts about the safety and efficacy of the largely untested vaccine beer. While he has promising data in mice that the vaccine works, he has so far reported antibody results in humans from his own sips of the brew. Normally, vaccines are tested in much larger groups of people to see how well they work and whether they trigger any unanticipated side effects. This is especially important for polyomavirus vaccines, because one of the desired uses is to protect people who are about to get organ transplants. The immune-suppressing drugs these patients must take can leave them vulnerable to harm from polyomaviruses.

Michael Imperiale, a virologist and emeritus professor at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, first saw Buck present his idea at a scientific conference in Italy in June. The beer approach disturbed him. “We can’t draw conclusions based on testing this on two people,” he says, referring to Buck and his brother. It’s also not clear which possible side effects Buck was monitoring for. Vaccines for vulnerable transplant patients should go through rigorous safety and efficacy testing, he says. “I raised a concern with him that I didn’t think it was a good idea to be sidestepping that process.”

Other critics warn that Buck’s unconventional approach could fuel antivaccine sentiments. Arthur Caplan, who until recently headed medical ethics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine, is skeptical that a vaccine beer will ever make it beyond Buck’s kitchen.

“This is maybe the worst imaginable time to roll out something that you put on a Substack about how to get vaccinated,” he says. Many people won’t be interested because of antivaccine rhetoric. Beer companies may fear that having a vaccine beer on the market could sully the integrity of their brands. And Buck faces potential backlash from “a national administration that is entirely hostile to vaccines,” Caplan says. “This is not the place for do-it-yourself.”

But the project does have supporters who say it could instead calm vaccine fears by allowing everyday people to control the process. Other researchers are on the fence, believing that an oral vaccine against polyomavirus is a good idea but questioning whether Buck is going about introducing such a vaccine correctly.

“I’m of two minds on this,” says Bryce Chackerian, a virologist at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque. Sometimes the government makes choices about who can take a vaccine based on what age you are or whether you have preexisting health conditions, he notes. “I’m sympathetic to Chris’s frustration with those sorts of constraints on vaccine uptake.”

Chackerian adds that he personally has no safety concerns about this particular type of vaccine. Still, he says, “I believe in our system of testing vaccines. I think it’s really important for making sure that we have safe products that go into people and that we don’t undermine the public trust in vaccines.” He calls Buck’s approach “a bold choice by him, but interesting and, I would say, not out of character.”

The painful dangers of polyomaviruses

Buck and his NCI colleagues have been working for more than 15 years to develop an injectable polyomavirus vaccine. Polyomaviruses are icosahedrons (think of 20-sided dice) with surface proteins that have a particular repeating pattern. The immune system views this pattern as “an innate danger signal,” Buck says. That makes them attractive vaccine candidates.

Polyomaviruses are everywhere and infect many people, causing serious problems for some but lying dormant in most humans. Up to 91 percent of people are infected with BK polyomaviruses by the time they turn 9 years old. BK is the species of polyomavirus that Buck is developing his vaccine against. Polyoma means “many tumors,” and the viruses are suspected to be involved in bladder cancers. Some evidence suggests these viruses also cause interstitial cystitis, a painful bladder condition in which people have a frequent or urgent need to pee. It affects about 1 to 3 percent of people in the United States.

In the blog post announcing the new results, Buck recounts a visit to a pediatric hospital where he learned that children with BK hemorrhagic cystitis screamed so loudly from bladder pain that the hospital had to install soundproofing. “There are screaming children at the back of my mind after that experience,” he says.

In addition, organ transplant recipients may suffer organ damage from polyomaviruses. That happens because transplant recipients take immune-suppressing drugs given to prevent rejection of the donated organ. Kidney transplant recipients may lose the organ because their weakened immune systems allow dormant BK polyomavirus in the donor kidney to reawaken and cause damage.

Other transplant patients can develop a brain disease caused by BK’s cousin JC polyomavirus. But transplant patients who have high levels of antibodies against polyomaviruses prior to surgery are often protected from such complications. Buck says transplant surgeons practically shake him by the shoulders to demand polyomavirus vaccines for their patients.

Those patients are part of what spurred Buck’s work — and his own experiences drove him to try and make it accessible outside the typical government approval process.

Buck often recounts how a friend was denied the vaccine for human papilloma virus, or HPV, because he was an adult man at a time when vaccine access was limited to adolescent girls. The friend later died of head and neck cancer sparked by that virus. Buck says that withholding vaccines from people who want them is morally equivalent to the evils of the Tuskegee experiment, a deeply racist and unethical program in which Black men with syphilis were denied penicillin so scientists could observe the effects of not treating the disease.

Ultimately, he hopes to win official approval for the yeast-based vaccine from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. But, he writes in the blog post, “there’s a glacial wall of license-wrangling, technical barriers, and impenetrable regulatory bureaucracy between me and the desperate families literally screaming for my help.”

The rise of a yeast-based vaccine

Buck’s NCI team has been working with a vaccine maker in India that holds the license to a traditional, injectable version of a polyomavirus vaccine that’s being tested in animals. That vaccine consists of BK polyomavirus’ outer shell protein, VP1, which is made in insect cells and then purified to strip out all but the viral proteins. These proteins naturally assemble into empty viruslike particles. When injected, the purified viruslike particles cause antibody levels in rhesus monkeys to shoot up well beyond a level that may protect against infection, the researchers reported in Vaccine in 2023. The protective response lasted for the length of the study; about two years.

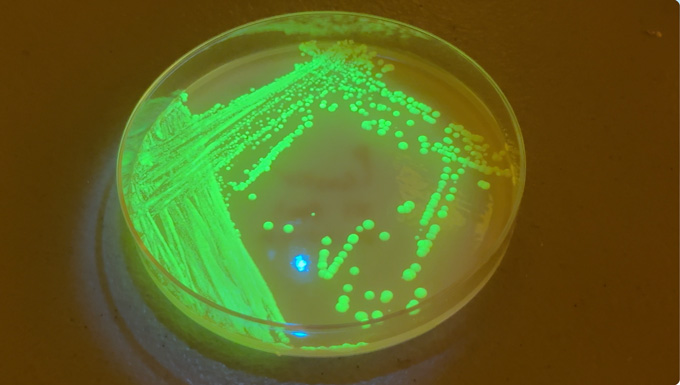

The results were so encouraging that Buck wondered if the vaccine could be delivered in other ways. And he wondered if it was really necessary to purify viruslike particles at all. For his virus factories, Buck decided to use Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the baker’s and brewer’s yeast that leaven bread and ferment wines, many beers, chocolate and coffee.

In his lab at NCI, his team sprayed ground-up yeast that make empty polyomavirus-like particles in mice’s noses, scratched it into their skin and fed it to them. Squirting particles up mice’s noses worked, though not as well as injecting purified particles did. Scratching the skin was also effective, Buck and colleagues report in their December papers. But feeding mice ground-up dead yeast didn’t work at all.

That’s not a surprise, Chackerian says. Oral vaccines against rotavirus, cholera and polio exist, so it’s a viable strategy. But in this case, the viruslike particles probably “just fall apart” in the acidic environment of the stomach, Chackerian says. Another challenge with developing oral vaccines is that many viral particles don’t interact with cells in the intestine. Viruses like polio naturally infect intestinal cells, so it’s no problem for weakened viruses in the oral polio vaccine to invade intestinal cells and prompt the immune system to erect defenses. Many scientists, including Buck, used to think oral vaccines work only if they consist of live, weakened viruses or bacteria that can infect intestinal cells.

Polyomaviruses are primarily found in the urinary tract. And Buck’s group wasn’t making a live virus. The yeast produce empty viral shells that can’t establish infection. S. cerevisiae yeast also do not cause infections in people, so Buck didn’t expect an oral polyomavirus vaccine to work.

Just to be thorough, the team fed mice whole, live yeast carrying the viruslike particles mixed with their kibble. The mice “love it and have a party when you give them the food,” Buck says.

Live yeast sprayed in the nose didn’t work — but the party kibble produced antibodies in the mice. That indicates that if they make it through the stomach, empty polyomavirus-like particles can interact with immune cells in the gut to produce antibodies, Chackerian says. It’s also a sign that live yeast might be able to ferry other types of proteins to build immune defenses against other diseases. “That’s a very exciting possibility,” he says, “because that would potentially mean that his findings aren’t just limited to this vaccine.”

With a little tinkering, Buck thinks yeast could deliver vaccines against a wide variety of diseases, including COVID-19 and H5N1 bird flu, as well as cancers caused by HPV.

A seismic shift in making a vaccine

The initial results from feeding mice the live yeast came as a shock even to Buck.

“We repeated this experiment a couple of times. I was reluctant to believe it,” Buck said at the World Vaccine Congress Washington in April. “It felt like an earthquake when I first saw the results emerging.”

The rumbling he felt was triggered by his knowledge of the way food and drugs are regulated in the United States. Buck realized he may not need FDA approval to get a polyomavirus vaccine into the hands of people who might benefit from it. “If you can eat something, you can sell it as a dietary supplement product” or food, he says. Such products are regulated differently than drugs or vaccines.

Vaccine and drug testing involves multiple rounds of clinical trials. These trials typically start with a few hundred people to establish whether there are obvious safety concerns. If there are no safety issues, larger trials involving thousands to tens of thousands of volunteers are conducted. There, scientists look for rare side effects that might not have been apparent in the smaller trial. Bigger trials can also give researchers clues about how well the vaccine works. Even after vaccines are approved, they are monitored for safety.

But Buck envisions vaccine beer as a food first. Food and dietary supplements don’t have to undergo multiple rounds of testing. Manufacturers of dietary supplements are supposed to establish their products’ safety before selling them, but that might be as simple as feeding samples to a few volunteers. Food and supplement makers also don’t have to prove to the FDA that their products work as advertised, although the FDA and the Federal Trade Commission ensure that manufacturers aren’t falsely advertising their products as cures for specific diseases.

Buck says the ingredients in his vaccine beer are already part of the food supply, and that the components meet the FDA definition of “generally regarded as safe” for people to eat. In addition, polyomaviruses are shed in massive quantities in urine and are aerosolized with every flush to float in the air and coat every bathroom door handle, so people probably unwittingly breathe in or consume millions of them daily, he says.

People who don’t drink beer could pour off the alcohol and eat the yeast. Buck is also experimenting with dried yeast chips or capsules of yeast but doesn’t have manufacturing infrastructure to produce large quantities of yeast. He hopes to enlist companies that make yeast for home brewers to make his vaccine beer yeast.

And here’s where things get sticky. “Vaccines are drugs. We all know this. There’s no hiding or costuming of vaccines. You should think of it as a drug,” Buck says. “But just because something is a drug does not mean it can’t also be a food.”

For instance, wormwood has been used for hundreds of years as a remedy against malaria. Nobel laureate Tu Youyou developed its active ingredient into the malaria drug artemisinin. Wormwood can be sold as dietary supplement or food but by law can’t claim to treat or prevent malaria. Vague claims, such as “supports immune health,” are allowed. But if someone wants to sell a product as both a drug and a food or supplement, the product must first be a food or supplement before being developed as a drug.

Andrew Buck set up a corporation specifically to sell the yeast strains Chris developed and has made sales to two scientists who are friends and supporters. The Buck siblings flirted with calling their invention “vaccine-style beer” to indicate that it is reminiscent of a vaccine, much the way India pale ales or Belgian-style beer are made in the mold of beers from those countries. They finally decided to call it vaccine beer so people would know its intended purpose even though the siblings don’t have irrefutable evidence that it works. “The place that we cannot go is saying that it is effective for any specific disease state,” Buck says. “The only way to do that is with full FDA approval” of the yeast as a vaccine.

Stirring up debate about trust in vaccines

Buck drank the first batch a pint a day over five days in late May. He followed that with two five-day booster flights seven weeks apart. Buck pricked his finger before and at regular intervals after drinking the beer to measure whether he was making antibodies against the virus. He already had antibodies against one of the four subtypes of BK polyomavirus but he was reassured to see levels of antibodies against BK type IV slowly climb after he drank beer containing the protein from that subtype. Antibodies against subtype II shot up even more rapidly.

Antibodies against subtypes I and II reached the threshold considered protective for transplant patients, but those against type IV didn’t make the mark. There are no blood test results from his brother or the other family members who quaffed the beer.

Buck says his self-experiment illustrates that a person can be safely immunized against BK polyomaviruses through drinking beer. But even though Buck produced antibodies, there is no guarantee others will. And right now, people who drink the vaccine beer won’t know whether they produce antibodies or if any antibodies they do produce will be sufficient to protect them from developing cancer or other serious health problems later.

Other scientists familiar with Buck and his yeast project also have conflicting opinions about how it might influence public trust and acceptance of vaccines.

If something were to go wrong when a person tried to replicate Buck’s beer experiment, Imperiale worries about “the harm that it could do to our ability to administer vaccines that have been tested, tried and true, and just the more general faith that the public has in us scientists. Right now, the scientific community has to think about everything it does and answer the question, ‘Is what we’re doing going to cause more distrust amongst the public?’”

That’s especially true now that health officials in the Trump administration are slashing funding for vaccine research, undermining confidence in vaccines and limiting access to them. A recent poll by the Pew Research Center found that a majority of Americans are still confident that childhood vaccines are highly effective at preventing illness. But there has been an erosion of trust in the safety of those vaccines, particularly among Republicans.

“Coming up with new modes of administration of vaccines is way overdue,” Caplan says. But given all the controversies swirling around vaccines, Buck’s do-it-yourself approach could backfire and “take a good idea he has and ruin it,” he says. “Vaccine doubts and fears and antivaccine attitudes could easily undercut what could be something useful.”

Preston Estep, a geneticist and entrepreneur who made his own DIY nasal spray vaccine against COVID-19, disagrees with Caplan’s assessment. “Bioethicists and public health officials often say that X, Y or Z is going to erode public trust in vaccines, and they actually don’t have any idea either whether or not that’s true,” says Estep, founder and chief scientist of the Rapid Deployment Vaccine Collaborative, a COVID-19 vaccine research and development nonprofit group. The group of scientists and citizen scientists from around the world tested Estep’s nasal vaccine on themselves months before COVID-19 vaccines became available, though there is only anecdotal data on its effectiveness. In 2024, the group shifted to a vaccine formulation that has been shown to produce immunity in animals.

If the vaccine beer proves effective and safe, it could build, not erode, public trust, Estep says. “It allows people to experience vaccines in a really prosaic sort of comfort food or comfort beverage approach.” And since Buck’s brother is selling yeast that people would need to homebrew into a liquid vaccine, “what I argue is that they’re not selling a vaccine, they’re selling a vaccine factory,” Estep says.

Buck says it’s more important than ever for people who want protection against diseases to have another option. Even with the Trump administration’s “saber-rattling, they cannot stop people from cooking in their own kitchen.” It’s not ideal to have to home brew your own vaccine, he admits. But “if nothing else works, or if the administration goes bananas and tries to shut it all down commercially, this is what we’re going to have to resort to.”

Buck feels a moral imperative to move forward with his self-experiments and to make polyomavirus vaccine beer available to everyone who wants it. “This is the most important work of my whole career,” he says. “It’s important enough to risk my career over.” What he’s doing in his home lab is consistent with his day job, he adds. “At the NIH in my contract it says my job is to generate and disseminate scientific knowledge,” he says. “This is my only job, to make knowledge and put it out there and try to sell it to the public.”

He doesn’t see himself as a maverick. “I’m not a radical who’s trying to subvert the system. I’m obeying the system, and I’m using the only thing that is left available to me.”

Read the full article here