This computer science professor became a billionaire launching four startups out of his privately-funded research lab, including unicorns Databricks and Anyscale. But it’s never been just about business.

Berkeley Professor Ion Stoica and his students don’t like being one-upped by anyone, let alone by archnemesis Stanford. That’s why, when a user asked for a way to compare their open-source chatbot Vicuna with the rival school’s Alpaca model, the Berkeley team pitted the bots against each other in a bloody AI battle.

The user community went wild. Soon, Stoica’s group added the ability to test random models side by side and let people vote on the battle outcome. It was all in good fun, explains associate professor Joseph Gonzalez, who worked on the project along with Stoica and his students We-Lin Chiang and Anastasios N. Angelopoulos.

Out of that fun came ChatBot Arena, a website that hosts over 400 AI models, allowing users to chat with multiple ones simultaneously. Rebranded as LMArena in April, with Stoica serving as chairman, Chiang as chief technology officer and Angelopoulos as CEO, the company has raised $100 million in VC funding at a $600 million valuation. The two-year-old outfit is already being used by developers like OpenAI, xAI and Google to test their chatbots, and has garnered over 3.5 million votes from users wanting to weigh in on these evolving models.

This is just the latest research initiative from Computer Science Professor Ion Stoica’s lab–which is mainly funded by private tech companies including Microsoft, Nvidia, Google and IBM–to make an industry splash. In his nearly three decades in academia, he has co-founded four startups with university colleagues and students, including two unicorns so far.

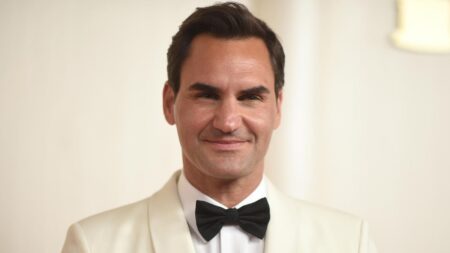

Born in then-communist Romania, Stoica—now age 60 and worth an estimated $2.5 billion—moved to the U.S. in the late 1990s to pursue a PhD in electrical and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. After graduating, he headed west to begin teaching at UC Berkeley in 2000, and he hasn’t abandoned his lab or students since. While most of his research is done with PhD candidates, he also continues to teach undergrads. This fall, for instance, he’ll teach a class on operating systems and system programming.

Stoica’s first startup, streaming analytics firm Conviva, came along in 2006, around the time YouTube went mainstream. It was born out of his collaboration with former colleagues from CMU, including his own PhD advisor Hui Zhang, who describes him as “one of the best researchers in the world.”

Stoica and Zhang had been conducting research on providing quality video streaming over the internet, and, after observing the emerging market, decided to turn it into a company.

Conviva, which last raised funding in 2017 at a $300 million valuation, acts as a smart watcher for online shows and movies, identifying sound and video issues and alerting streamers. It also offers reports on what everyone is watching, which parts they skip, and what they like, serving clients like Fox and Peacock. Despite no longer having an official title within Conviva, which is based in Foster City, California, Stoica, remains on the board and says he meets with the team weekly. “We have the potential to be the next Databricks,” says Zhang, who is Conviva’s CTO, referring to the $62 billion data analytics firm that Stoica cofounded with six other Berkeley researchers.

Itwas Databricks that first made Stoica (and at least two of his Berkeley cofounders) billionaires. In 2013, Stoica set out to discover how to process huge amounts of data more effectively with Ali Ghodsi, a visiting scholar from the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and five PhD students. Together, they developed Spark, a piece of predictive software that serves as a powerful data-processing tool.

Stoica wanted to turn Spark into a startup to encourage users to take the lab’s research more seriously, according to Matei Zaharia, one of the PhD students who cofounded Databricks and is now an associate professor at Berkeley.

Plus, he wanted to help smaller companies without sophisticated infrastructure manage and analyze massive amounts of data for both business insights and building AI tools.

The company projected that annualized revenue would hit $3.7 billion by this July, and has been rumored to be eyeing the public market for years.

Not that the latter was Stoica’s intention. “I’m still an academic at heart,” he says. For him, the goal was never to get rich. “If you are just driven by the money, you go do an IPO. That’s the easiest way. But it’s not that. It’s about building something meaningful.” Stoica was CEO of Databricks from 2013 to 2016, when he handed off the reins to Ghodsi and transitioned into the role of executive chairman. “Staying beyond that meant quitting Berkeley. So I had to choose,” he says, “And I chose to go back.”

The reason he never went into business full-time is his students: “Young people in their formative years, sometimes they don’t know what is possible or not…They have this kind of belief, and that’s why you are going to get unexpected solutions,” he explains. Plus, Stoica credits his business success to his research focus: “It’s the act of creation…exploring new ideas.”

“I was thinking he probably got to be really high [up] by not caring too much about research problems. But it turned out I was wrong. He really cares about research values,” says Yang Zhou, one of his current post-doctoral students.

AtBerkeley, Stoica has a reputation not just as a good teacher, but as a great sounding board for business ideas and, even more importantly, a person to help get these ideas off the ground with funding.

It’s that reputation that brought him the students with whom he would co-found Anyscale – the second billion-dollar company in his portfolio.

Six years after Spark’s creation, Philipp Moritz and Robert Nishihara, two PhD students of another Berkeley computer science professor, Michael Jordan, set out to fix a defect that required Spark to wait for every task to finish before moving on to the next operation.

“I said they’re not going to get a lot of leadership from me. I’m not a systems builder,” recalls Jordan. So, he encouraged them to take Stoica’s distributed systems class, where they worked with him on a solution.

That project became Ray, a software designed to handle large-scale reinforcement learning more efficiently than synchronous systems like Spark. “In typical Ion style, it was very quickly that he wanted to turn that into a company,” says Jordan, who helped start the company along with Stoica and his students.

That’s how Anyscale got started in 2019. Within three years, the company, a platform that helps developers scale their AI applications, had raised $260 million, including $200 million at a $1.4 billion valuation in its most recent funding round in September 2022. Stoica, who is executive chairman of the San Francisco based company, says Anyscale is doing “very well” and will be raising additional funding within the next 12 months.

“He likes seeing these problems and trying to understand…how to really solve them. Which is what makes great research and what makes great business,” says associate professor and LMArena researcher Gonzalez of his colleague.

And the key to solving problems, according to Stoica, lies in the universities. “Everyone can use [university research]. Compare this with a company…They are not going to publish…They are not going to open-source their best systems.” Both Databricks’ Spark and Anyscale’s Ray started as open-source projects and are available to the public to this day.

Stoica’s lab has not suffered from the Trump administration’s funding cuts, and likely won’t anytime soon: “We are in a more fortunate position,” he explains. The computing lab at Berkeley, which has a current annual budget of over $6 million, has been privately funded by big tech companies including Google and IBM since the early 2010s. It also receives funding from Stoica’s own company Anyscale.

But some of his fellow Berkeley researchers have felt the impact, which has halted projects at the school on everything ranging from making classical literature more accessible to fighting climate change – and are suing over it.

One of the most successful professors at Berkeley, Stoica is now chairing a task force to address research funding cuts across the entire college of computing, data science, and society, according to dean Jennifer Chayes. As chair, he’s encouraging fellow professors to go after private funding, mimicking the model that has brought his own lab so much success.

“He is leading that with incredibly creative ideas about how to go out to companies and how to go out to VCs,” says Chayes.

The more than 80 students who have been personally mentored by Stoica have benefitted from his resources and connections. They are overwhelmingly employed within academia or the startup scene, including at least 7 who work at Databricks.

But the tech job landscape isn’t as kind to everyone. Computer science graduates, once among the most in-demand applicants, have been struggling to find employment as AI leads companies to scale back their workforces.

“What I’m telling students is to embrace and to use these [AI] tools,” says Stoica, “It’s clear that there is going to be some short-time pain. But think from another perspective.” Stoica believes AI is about accelerating the pace of human evolution and eventually becoming an interplanetary civilization.

“If you’re seeing it this way,” he says, “[We] still don’t have enough people to do it.”

Read the full article here