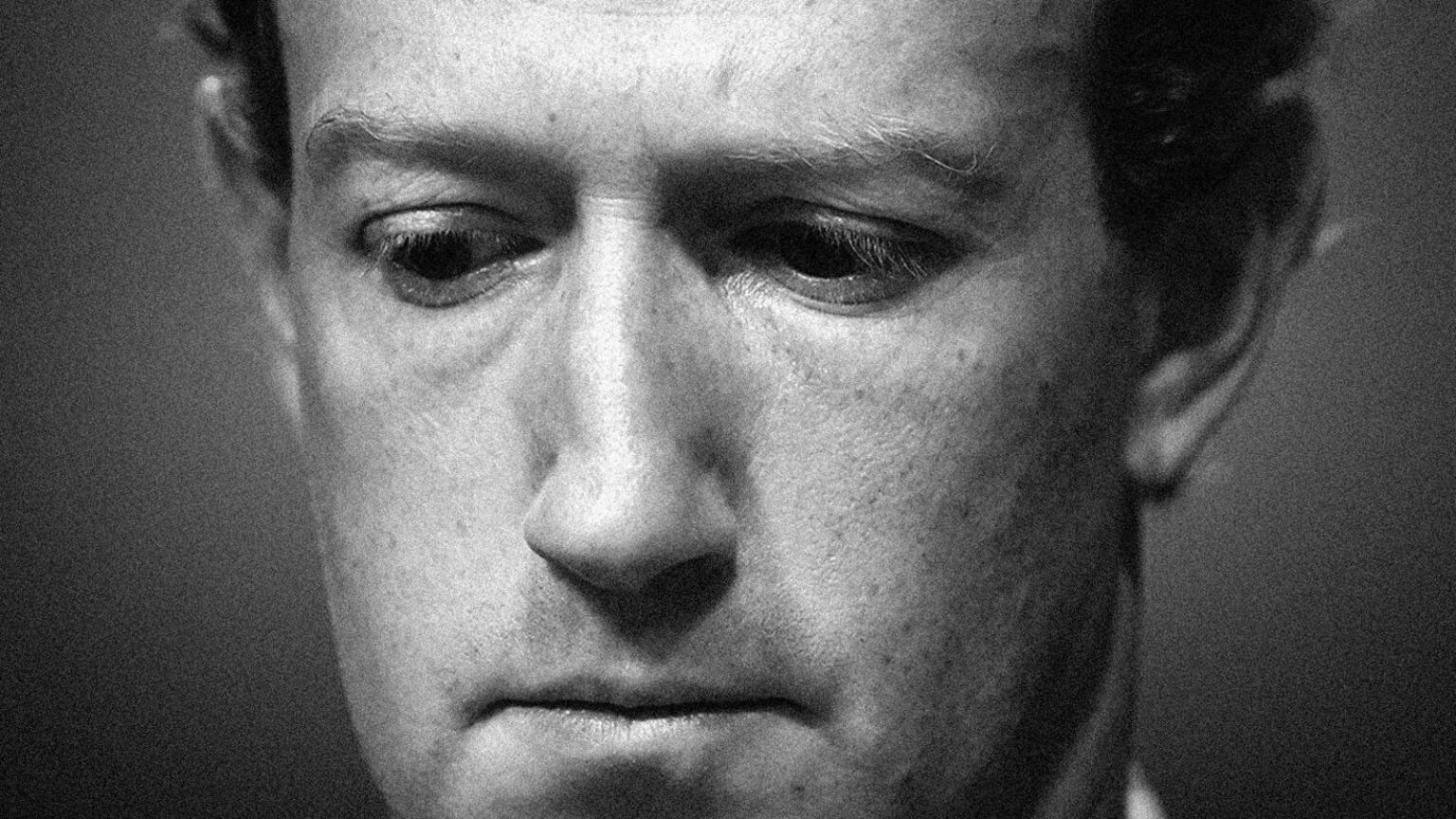

At Meta, a chaotic culture and lack of vision have led to brain drain, with rivals saying its AI talent is lackluster. But Zuckerberg’s frenzied hiring spree hasn’t stopped the exodus.

Meta was teeming with top AI talent, until it wasn’t. Years before Mark Zuckerberg’s high-profile shopping spree, the company employed the researchers and engineers that would ultimately depart to start major AI companies: founders of Perplexity, Mistral, Fireworks AI and World Labs all hailed from the Facebook parent’s AI lab. And as the AI boom has spurred the build of ever more capable models, others have decamped to rivals like OpenAI, Anthropic and Google.

The brain drain of the last few years has been tough, three former Meta AI employees told Forbes. “They already had the best people and lost them to OpenAI… This is Mark trying to undo the loss of talent,” one ex-Meta AI employee said. And even as Zuckerberg makes jawdropping offers for top tier AI researchers, the social media giant continues to lose those that are left.

Today, when it comes to recruiting high-caliber AI researchers, Meta is often an afterthought. Insiders at some of Silicon Valley’s biggest AI companies said that prior to the fresh hiring of the last few months, Meta’s talent largely didn’t meet their hiring bar. “We might be interested in hiring some of the new people Mark is hiring now. But it’s been a while since we were particularly interested in the people who were already there,” a senior executive at one of the major frontier AI companies told Forbes.

Google has hired less than two dozen AI employees from Meta since last fall, according to a person familiar with Google’s hiring, compared to the hundreds of AI researchers and engineers it hired in that time frame overall. That person told Forbes the “prevailing belief” is that Meta didn’t have much talent left to poach from. Google declined to comment.

This has lent an air of desperation to Zuckerberg’s attempts to raid the likes of OpenAI and Thinking Machine Labs, the fledgling startup helmed by former OpenAI CTO Mira Murati, with nine-figure offers and promises of near-unlimited compute. In at least two cases, the Meta CEO has offered pay packages worth over $1 billion spread across multiple years, according to The Wall Street Journal. He reportedly poached at least 18 OpenAI researchers, but many have also turned him down, betting on bigger impact and better returns on their equity.

“Meta is the Washington Commanders of tech companies,” one AI founder told Forbes, referring to the NFL team in its pursuit of free agents. “They massively overpay for okay-ish AI scientists and then civilians think those are the best AI scientists in the world because they are paid so much.”

Meta strongly denied that it has had issues with AI talent and retention. “The underlying facts clearly don’t back up this story, but that didn’t stop unnamed sources with agendas from pushing this narrative or Forbes from publishing it,” spokesperson Ryan Daniels said in a statement.

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei has said he’s spoken to Anthropic employees who have gotten offers from Meta who didn’t take them, adding that his company wouldn’t renegotiate employee salaries based on those offers. “If Mark Zuckerberg throws a dart at a dartboard and hits your name, that doesn’t mean you should be paid ten times more than the guy next to you who’s just as skilled, just as talented,” he said last month on the Big Technology Podcast. Anthropic declined to comment.

Anthropic has an 80% retention rate, the strongest among the frontier labs, according to a May report by VC firm SignalFire. The findings are based on data collected for all full-time roles including engineering, sales and HR, and not AI researchers specifically. In comparison, DeepMind has 78%, OpenAI 67% and Meta trails with 64%.

An August report from the firm that focused broadly on engineering talent noted that Meta is aggressively hiring engineers across the company twice as fast as it is losing them. “Some outbound movement helps explain why Meta is investing so heavily in rebuilding and expanding its technical bench,” said Jarod Reyes, SignalFire’s head of developer community. “It reflects the intensity of competition for senior AI talent and the pressure even top companies feel to backfill experience while scaling new initiatives.”

In June, Zuckerberg hired Alexandr Wang, the 28-year-old former CEO of data labeling giant Scale AI and acquired a 49% stake in the company. Wang has been tasked with leading a new lab within Meta focused on building so-called “superintelligence”— an artificial intelligence system that outperforms humans in a range of cognitive tasks. He was joined by Nat Friedman, a prominent AI-focused investor and former CEO of GitHub, as well as about a dozen top researchers freshly poached from OpenAI, Google DeepMind and Anthropic, some of whom had been reportedly offered $100 million to $300 million pay packages spread over four years. (Meta said the size of the offers was being misrepresented.) In late June, Meta hired Daniel Gross, prominent AI investor and former CEO of $32 billion-valued AI startup Safe Superintelligence, which he cofounded with former OpenAI research chief Ilya Sutskevar.

Zuckerberg has also tried to win back people Meta previously lost, re-hiring the company’s former senior engineering director Joel Pobar and former research engineer Anton Bakhtin, who’d left to work at Anthropic in 2023, according to The Wall Street Journal. They did not respond to requests for comment.

Meanwhile, people are still leaving the company. In 2024, the Facebook parent was the second most-poached tech giant across all full time roles, with 4.3% of new employees at AI labs coming from the company, according to the May SignalFire report. (Google — excluding its DeepMind unit — was the top-raided tech giant.)

Last week, Anthropic hired Laurens van der Maaten, formerly a distinguished research scientist at Meta, who co-led research strategy for the social giant’s flagship Llama models, as a member of Anthropic’s technical staff. In June, enterprise AI startup Writer recruited Dan Bikel, a former senior staff research scientist and tech lead at Meta, as its Head of AI. At Meta, Bikel led applied research for AI agents, systems that can autonomously carry out specific actions. Cristian Canton, who led Responsible AI at Meta, left the company in May to join public research center Barcelona Supercomputing Center. The company lost Naman Goyal, a former software engineer at FAIR, and Shaojie Bai, a former senior AI research scientist, to Thinking Machine Labs in March. And Microsoft has reportedly created a list of its most-wanted Meta engineers and researchers, and has also mandated matching the company’s offers, according to Business Insider.

At French AI startup Mistral, at least nine AI research scientists have come directly from Meta since the startup’s founding in April 2023, according to LinkedIn searches conducted by Forbes. At Meta, they worked on training early versions of Llama. Two of these hires were made within the last three months. And Elon Musk recently claimed xAI had recruited several engineers from Meta, without shelling out “insane” and “unsustainably high” amounts of money on compensation. Since January, xAI has hired 14 Meta engineers, Business Insider reported.

A Culture of Chaos

In December 2013, Meta started FAIR, its internal lab dedicated to AI. (Launched as Facebook AI Research, it repurposed the F to stand for “Fundamental” after the company rebranded to Meta in 2021.) Led by renowned NYU professor Yann LeCun, it was regarded at the time as one of the best employers for people looking to build cutting edge AI. The lab contributed to pioneering research on computer vision and natural language processing. Those were the “golden days of AI research,” said one former Meta research scientist.

In February 2023, the company consolidated its AI research under a more product-focused team called GenAI instead of FAIR. While FAIR is still around, it has been “dying a slow death” within Meta, where it has been allocated fewer compute resources and has suffered from major departures. “Zuck should never have made FAIR less important,” that research scientist said. Meta denied at the time that FAIR has faded in importance and instead said that it is a new beginning for the lab, where it can focus on more longer term projects. Meta said FAIR and GenAI work closely together, which helps better coordinate across the two teams and make decisions faster.

The newly-formed GenAI team was asked to sprint, working late nights and weekends to ship AI products, like Meta’s conversational AI assistant and the AI characters that Zuckerberg would later unveil to the world at 2023’s Meta Connect, the company’s annual product conference, a third former senior researcher said. “We basically had six months to go from pretty much nothing to shipping,” said that senior researcher, who was plucked from another team to join GenAI, which started with 200 to 300 employees and grew to almost 1,000.

As the AI race intensified, so did the sprint to continue shipping products in 2024 and 2025, they said. “We went like bananas, working our tails off for the entire year.” But over time, the sprints started to feel more chaotic — senior leaders disagreed on technical approaches like the best way to pretrain models, teams were given overlapping mandates and people fought for credit, two ex-Meta AI employees said. Teams would be formed and disbanded in a matter of weeks, forcing researchers to frequently switch their focus on to different projects. One of the former AI researchers, who spent three years at Meta, said he shuffled through seven managers during his time there.

One of the former senior AI researchers said the Metaverse — Zuckerberg’s long term vision for a 3D world where people could interact with each others’ avatars — was a messy roadblock. Having already drawn billions of dollars and resources, leaders at the company claimed the Metaverse was a priority for the tech giant in late 2022, even as AI grew in prominence. That year, the researcher was reassigned to Meta Horizon, the metaverse’s platform for VR games and virtual spaces. “They didn’t really know what to do with all of us, and it was kind of an ill-fated move. And thankfully, the GenAI org formed and we got out of there,” they said. Meta spokesperson Daniels didn’t comment on these claims.

Got a tip for us? Contact reporters Rashi Shrivastava at rshrivastava@forbes.com or rashis.17 on Signal, and Richard Nieva at rnieva@forbes.com or RNieva.26 on Signal.

Employees had to demonstrate business impact in biyearly performance reviews, like if their datasets were used to train models or if the models they worked on scored highly on specific benchmarks, a fourth former AI researcher told Forbes. Those who couldn’t risked losing their jobs. “People start grabbing scope, making sure that nobody else works on the projects that they’re already working on, so that makes collaboration more difficult,” they said. Daniels said this review process is consistent for employees across the company.

Many of these claims are echoed in a recent nine-page essay titled “Fear the Meta culture” that Tijmen Blankevoort, a former AI research scientist at Meta, posted in the company’s internal communication channel for the AI group. Blankevoort wrote in a public Substack post that he felt things at Meta “were going off the rails.” “Many people felt disheartened, overworked and confused,” he wrote, saying employees were afraid of being fired, team assignments changed regularly, and leaders had a “wavering vision.”

Blankevoort did not respond to a request for comment, but after the essay leaked, he wrote a follow up post claiming that the document was meant for internal constructive criticism, and not meant to be a “raging ‘mic drop.’” Meta’s Daniels said Blankevoort’s account “isn’t surprising.” “We’re excited about our recent changes, new hires in leadership and research, and continued work to create an ideal environment for revolutionary research,” he said.

Meta’s AI reputation took a hit in April when it released Llama 4. The model was seen as a let down, both inside and outside the company, and was widely criticized for poor reasoning and coding skills. To make matters worse, the company was accused of artificially boosting Llama 4’s benchmark scores to make its performance look better than it actually was, allegations the company denied. “Llama 4 was a disaster,” one of the former researchers told Forbes.

Now, Meta’s flashy new superintelligence lab is raising more questions about where the company’s efforts are headed. “People are wondering where they fit in and they feel like they are being pushed to the side,” the ex-research scientist said.

Merceneries versus Missionaires

For rivals trying to fend off Zuckerberg’s shock and awe financial incentives, the view is that he’s appealing to mercenaries available to the highest bidder. The pitch is that they are antithetical to Meta because they attract true believers and “missionaries.”

“I am proud of how mission-oriented our industry is as a whole; of course there will always be some mercenaries,” OpenAI chief Sam Altman wrote in a July letter to staff. “Missionaries will beat mercenaries,” he added, noting “I believe there is much, much more upside to OpenAl stock than Meta stock. But I think it’s important that huge upside comes after huge success; what Meta is doing will, in my opinion, lead to very deep cultural problems.” OpenAI has responded to the pressure by reportedly adjusting salaries and giving bonuses of up to millions of dollars to research and engineering teams.

“Big tech has got such a mercenary view right now of this race of the need to control the output of the technology that we are all gunning towards, AGI,” said May Habib, CEO of enterprise AI startup Writer. “There is a humanity that I think is lost as I listened to candidates really describe the culture inside of the companies that they are leaving.”

One AI startup founder described a “cultural shift” within Meta, saying he’s started to see a larger pool of applicants from the company. “We tend to hire more missionaries than mercenaries. So we’re not offering people $2 billion to join. We don’t need to. We also don’t have $2 billion to offer people salaries,” he said.

Facebook, of course, has also dealt with its share of baggage that might make it a difficult sell for newcomers. Over the last decade, the tech giant has limped through controversies related to election interference, radicalization, disinformation, and the mental health and well-being of teens. LeCun, who did not respond to interview requests, has previously acknowledged that those black eyes could impact public perception of the company’s research lab as well. “Meta is slowly recovering from an image problem,” he told Forbes in 2023. “There’s certainly a bit of a negative attitude.”

Read the full article here