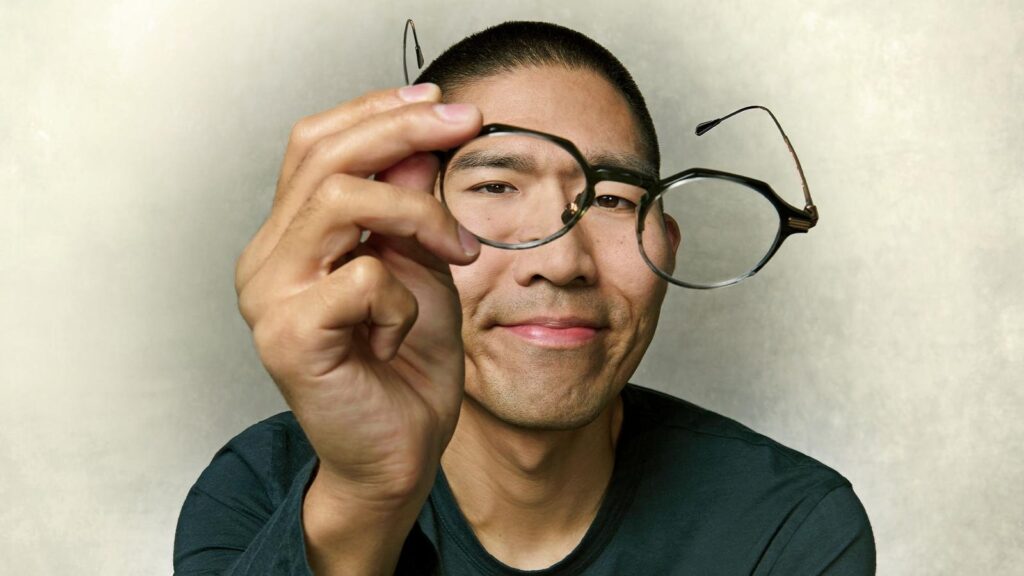

An alum of Google, Facebook and Twitter, Edwin Chen built his data labeling company, Surge, in the background of the AI revolution. Now the youngest member of the Forbes 400 is ready to step out of the shadows and make his voice heard.

After a morning spent reviewing a dataset, reading research papers and playing with cutting-edge AI models in his Manhattan Apartment, Edwin Chen takes a short walk to the swank three-story Starbucks Reserve Roastery on Ninth Avenue.

Dressed in a Vuori navy T-shirt with a tiger-adorned canvas tote slung over one shoulder, Chen heads downstairs and settles in at a dark corner table. Sipping a small green tea “because ordering coffee here takes too long,” the founder and CEO of Surge AI, a data labeling and AI training firm, then launches into a nonstop two-hour discussion about everything from Silicon Valley culture (he hates it) to his rivals (“they’re all body shops”) to how humans might interface with aliens if they came to Earth. “They don’t speak English. So how would you communicate with them? How would you decipher their language? Hopefully there’ll be some mathematical way to do it.”

This dilemma is also explored in his favorite short story, a 1998 piece by science fiction author Ted Chiang. “Story of Your Life” became the basis for the movie Arrival, in which a linguist tries to talk to aliens by identifying patterns in their speech and writing. It was also part of Chen’s inspiration for starting Surge in 2020, he says, adding that he wants his data labeling company to encode the “richness of humanity.” For him, that means getting the smartest humans (including professors from Stanford, Princeton and Harvard) to train AI, translating their specialized knowledge to the 1s and 0s underpinning large language models. In addition to the Ivy League brainiacs, Chen employs an army of a million-plus gig workers from more than 50 countries around the world who help come up with questions that might stump AI, evaluating the models’ responses and writing criteria that help AI generate a perfect response. “I really do think that what we’re doing is so critical to all the AI models that without us, AGI [artificial general intelligence, tech lingo for when AI will match or surpass human capabilities] just won’t happen,” Chen says. “And I want it to happen.”

Long-winded, brilliant and eccentric, Chen is perhaps the most successful tech entrepreneur you’ve never heard of. That’s because until very recently he wanted it that way, despite being well known in the AI community. The data scientist who did stints at Twitter, Google and Facebook eschewed traditional venture capital and left the Bay Area fishbowl seven years ago, electing to fund Surge himself, starting with “a couple million” of savings from his decade in Big Tech. “One of the reasons why we bootstrapped is that I’ve always hated the Silicon Valley status game,” says Chen, who describes the typical VC-backed Valley startup as a “get-rich-quick scheme.” He also hates the idea of raising so much money and then needing to spend it. In his opinion, that leads to massive overhiring. He points out that Surge has just 250 employees, including full-time, part-time and consultants. By contrast, Scale AI, its big rival, has four times as many staffers with less revenue.

Surge, which helps tech companies get the high-quality data they need to improve their AI models, brought in $1.2 billion in revenue in 2024, less than five years after its founding, from customers including Google, Meta, Microsoft and AI labs Anthropic and Mistral. (It helped train Google’s Gemini and Anthropic’s Claude.) It’s been profitable from nearly day one, according to Chen. Based on those numbers, the company is worth an estimated $24 billion. Surge is in talks to raise $1 billion at a $30 billion valuation, though the round hasn’t closed yet.

Chen’s decision to fund Surge himself has paid off handsomely: His approximately 75% stake in it is worth an estimated $18 billion, enough to make him the wealthiest newcomer on this year’s Forbes 400 list of the richest Americans. At age 37, he is also the youngest member.

Surge claims its approach isn’t like older forms of data labeling, in which people—often from less developed countries in the Global South—are paid pennies per hour to sit in front of computers and identify the difference between a cat and a dog. Instead, Chen’s data annotators, which include professionals and professors, follow a set of instructions to interact with online chatbots. They might be asked to try to prompt the chatbot into spitting out a wrong or toxic response. Then they write a better response. Or they might be asked to compare different AI responses to the same question and explain why one is better.

By revenue, Surge is the largest in the business right now, but competitors including Scale AI (of which Meta bought 49% for $14 billion in June), Turing, Mercor and Invisible AI are moving fast. Companies spent $104 billion on AI infrastructure in 2024, tech research firm International Data Corporation estimates, and are on pace to spend more this year. “Data is an important part of that infrastructure, just like compute [raw processing power] and energy is,” says Jonathan Siddharth, CEO of Palo Alto, California–based Turing. “I think it makes sense for a company to spend anywhere between 10% to 20% of their compute spend on data.” Everyone wants a piece of the pie: In May, Jeff Bezos led a $72 million investment in Netherlands-based data labeling company Toloka. Ride-sharing giant Uber began labeling its own data in 2024. Legacy players like Australia-based Appen, which is increasingly serving Chinese model makers, are also rebranding to focus on generative AI.

Have a tip? Contact Phoebe Liu at 678.834.4200 (phone/WhatsApp/Signal) or [email protected].

All along, quietly in the background, Chen has been building his company and its reputation. “I think [Surge] just doesn’t want to reveal anything in what they do,” says a current Meta researcher. But as the industry evolves, Chen is no longer content to stay behind the scenes. He has serious concerns that today’s AI models are optimized for the wrong things, sending users down a “delusional rabbit hole” akin to how YouTube and Twitter algorithms were largely optimized for clickbait when he worked at those places. He wants Surge to help “steer the AI industry”—which means positioning himself as more of a thought leader. About time, says the Meta researcher. “Surge is really good, and people know it. I was asking [Chen], ‘Why do you think you are not that famous?’ ”

Chen grew up in Crystal River, Florida (population 3,400), a Gulf Coast city better known for manatees and retirees than tech billionaires. His parents, who immigrated to the U.S. from Taiwan, ran Peking Garden, a Chinese-Thai-American restaurant, where Chen worked when he was a teen.

His real appetite was for languages and math, in relation to one another. In his words: “I was always interested in the mathematical underpinnings of language.” As a kid, he wanted to learn “like 20 languages” and loved spelling bees. Today he still speaks a bit of French plus some Spanish and Mandarin (Hindi and German have fallen by the wayside). Math came easily to him but didn’t truly capture his imagination until he began noticing distinctive patterns in numbers, “especially number three,” found in everything from flower petals to mountains.

Chen, who took calculus in eighth grade, says he got a full ride for his last two years of high school at the elite Connecticut boarding school Choate, whose alumni include John F. Kennedy, John Dos Passos and Ivanka Trump. After exhausting Choate’s math curriculum, he spent most of his senior year researching whatever caught his fancy under Yale professors who also taught at Choate. Then came MIT, where he majored in math, cofounded a linguistics society and operated on a polyphasic sleep schedule, which means dividing sleep into multiple short rests—for instance, a 30-minute nap every six hours rather than one eight-hour snooze.

After three years at MIT, Chen interned at Peter Thiel’s former San Francisco hedge fund and liked it so much he never returned to school. Having completed the required coursework, he applied for a degree and received it two years later. Then came his stints at Twitter, Google and Facebook, where he worked in various positions that involved content moderation and recommendation algorithms. In each role, Chen kept running into the same problem: It was difficult to get high-quality human-labeled data at scale. He left his last job at Twitter in 2020 to solve this riddle on his own and incorporated Surge that year. “I’ve been building early versions of this system for the past 10 years,” he says.

Everything Chen does is mindful. A vegan who gets in 20,000 steps most days, he says he does some of his best thinking walking around New York. Once or twice a week he’ll stroll up to Times Square at midnight. “I love seeing this mini-representation of humanity—Broadway actors, tourists from around the world, night-shift workers, artists—surrounded by lights and technology and infrastructure.” He’s an Eminem superfan, but here he quotes a lyric from Jay-Z and Alicia Keys’ “Empire State of Mind”: “These streets will make you feel brand new, big lights will inspire you.”

He was sick of data annotation that was “complete junk” from people who either didn’t get paid enough to care or didn’t have the requisite cultural or political knowledge to make an informed judgment. One example: An annotator unfamiliar with U.S. elections might rate a social media comment of “let’s go Brandon!” as “positive.” Surge looked to hire people who understood context and had a deep understanding of language. In 2021, Chen received an interesting email from the brother of a software engineer he had tried to hire. The brother, Scott Heiner, had almost no tech experience; he’d been a drummer and tour manager for indie-pop artists such as Alec Benjamin for more than a decade. Attached to the email, though, was a famous David Foster Wallace essay discussing who has the right to define “correct” English. Chen was intrigued and hired Heiner in October that year as Surge employee number five, despite the fact that he’d never worked in tech before. Says Heiner of Chen: He’s a “completely nontraditional thinker.”

In an interview, Chen is just as likely to ask a job candidate to discuss Wallace’s work or linguistics as he is to ask them to code or problem-solve on a whiteboard. Approximately 20% of Surge’s staff have a nontraditional background. “We value creativity,” Chen says.

He also brings his own approach to other parts of the business. Forgoing traditional sales and marketing, he initially communicated through his popular data science blog, which he started in his spare time more than a decade ago. That’s where Surge got its first customers, he says, though he won’t specify which ones. Among the earliest were Airbnb, Twitch and his former employer Twitter. He tries to pitch directly to tech firms’ data scientists, assuming they will recognize the quality of Surge’s data and be more willing to pay for it. (Surge charges 50% to ten times more than competitors, per two researchers.)

One researcher at Google called Chen on a Saturday night in May 2023 at the recommendation of coworkers. At the time, Google’s Gemini family of AI models were “in pretty bad shape.” The call lasted more than two hours. Soon after, Google signed a contract with Surge that grew to more than $100 million per year. “ You feel like you’re paying for quality in one case versus paying for man hours,” says the researcher, who has since left Google and asked not to be identified.

AI startups can be tight-lipped, but even compared to its peers, Surge stands out. Its biggest customers don’t know exactly what makes its data better. (On the flip side, Surge and its competitors have little idea whose data actually ends up training models like Gemini, Claude or OpenAI’s GPT.) Surge won’t share how it matches participants to projects, collects its data or how it’s annotated. All its customers get for their millions is a link to a dataset.

This allows Surge to more closely monitor annotators’ performance, using hidden quizzes, manual reviews by more highly rated annotators and (of course) machine learning algorithms that optimize for “performance” and can be pretty “adversarial,” Chen says. He maintains that Surge’s quality controls and deep technical expertise are its secret ingredients.

As for being secretive, Chen says it’s not intentional but that Surge has been “too busy to discuss our work externally.” Plus Surge operates under nondisclosure agreements with its customers. And it hires annotators through a wholly owned affiliate called DataAnnotation Tech. Neither its job listings nor the website used by annotators mentions Surge by name—meaning the workers might not know Surge is the company behind it. The work pays at least $20 an hour and more than $40 an hour for more specialized tasks, which doesn’t seem like a lot for top talent. “If you’re a good worker [and] you’re very smart and you have a lot of knowledge,” Chen says, “we want to be a platform where you can work full-time.”

Heard on the Playground

AI entrepreneurs might be brainiacs, but that doesn’t mean they’re above a little trash talk.

On rare occasions Surge will even put annotators on staff, as it did with Juliet Stanton, a former New York University professor of linguistics who has a doctorate from MIT. Stanton began contracting with Surge in April 2024 “to earn some extra cash” and is now a full-time employee. The company looks for people “capable of analytical and creative thinking,” she says, adding that Chen wants annotators to help AI capture different cultural and social contexts in various languages. For example, the language you’d use to talk to a friend is different from that which you’d use to speak to your boss. Some languages even have different words for romantic and non-romantic contexts—all things human data annotators can help teach AI.

But an army of hourly workers, many of whom annotate data as their main gig but receive no benefits, is also an invitation for legal action. Surge and Scale both face class action lawsuits in California alleging that they misclassified full-time workers as independent contractors to dodge having to pony up for benefits like vacations and health care. “Surge AI’s willful decision to exploit its workers for profit is part of a broader trend we’ll continue to see as tech giants race to dominate the AI space, unless we hold them accountable,” Glenn Danas, partner at Los Angeles–based Clarkson Law Firm, said in a statement to Forbes. “At its core, what Surge AI is doing is wage theft on a massive scale.” Replies Chen: “We believe the suit to be without merit.” He and Scale spokesperson Joe Osborne both say they are committed to defending their companies vigorously; both cases are ongoing.

The existential question for outfits like Surge: As AI advances, will there come a time when there is no need for human data annotations? Models like Meta’s Llama 4, released in April, already relied heavily on AI creating and labeling its own data, so-called “synthetic data,” per a Meta researcher. Surge uses a “human-in-the-loop” variation to this approach, in which AI generates its own data and labels it but humans critique its performance. Chen feels strongly that humans are vital. When people and AI work together, he says, they surpass anything either could have done separately. But even if humans remain tangentially involved, a greater emphasis on machines training themselves would affect his bottom line, since training would get much cheaper. Another issue for Surge: The tsunami of VC money sloshing over rivals. Flush with cash, they don’t have to worry much about profitability (at least in the short run), putting downward pressure on margins across the industry. Two key Surge customers have already moved on. An OpenAI spokesperson confirmed that it no longer works with Surge (competitors Mercor and Invisible have each said OpenAI is a customer). Cohere, the AI lab that was one of Surge’s earliest customers, has essentially moved all its data annotation in-house. Ultimately, AI model makers don’t have much—if any—loyalty. Most of Surge’s customers also contract with its competitors. Meta, for example, still uses Surge even after spending billions to buy half of Scale.

“It is not a winner-takes-all market,” says Turing investor and Foundation Capital partner Ashu Garg. If AI and data services businesses can tap into the IT budgets of the world’s largest companies and chip away at the market share of traditional IT services players, he says, it could become a trillion-dollar market.

Regardless of how the industry evolves, Chen plans to run Surge until artificial general intelligence occurs, assuming it occurs at all. Sam Altman, for one, is certain that AGI is imminent. Chen’s estimate is more conservative. He thinks it’ll arrive on the scale of 20 years.

Thinking about the future, Chen says he is “fundamentally uninterested in being acquired” and has no intention of an IPO. “Why would anyone want to go public? A big problem with public companies is they always have to worry about the short term.” Head of product Nick Heiner has another theory: “If Surge didn’t exist, what would Edwin do for fun? He’d probably make data and train AI. It just happens to be a lucrative thing. But it’s like watching Michael Jordan dunk. It’s just the thing that this guy was made to do.”

Read the full article here