Over the weekend, Cuban authorities announced that 32 Cuban nationals had been killed in the US’s raid on the Venezuelan capital, Caracas. They were serving as bodyguards to President Nicolás Maduro in the military compound from which US special forces seized him.

Besides Venezuela itself, Cuba has been hit harder than any other country by Maduro’s removal. Havana lost a key political ally and a pillar of its already troubled economy, and statements from the Trump administration in the raid’s aftermath made it clear that along with Colombia and Greenland, the US could soon target Cuba as well.

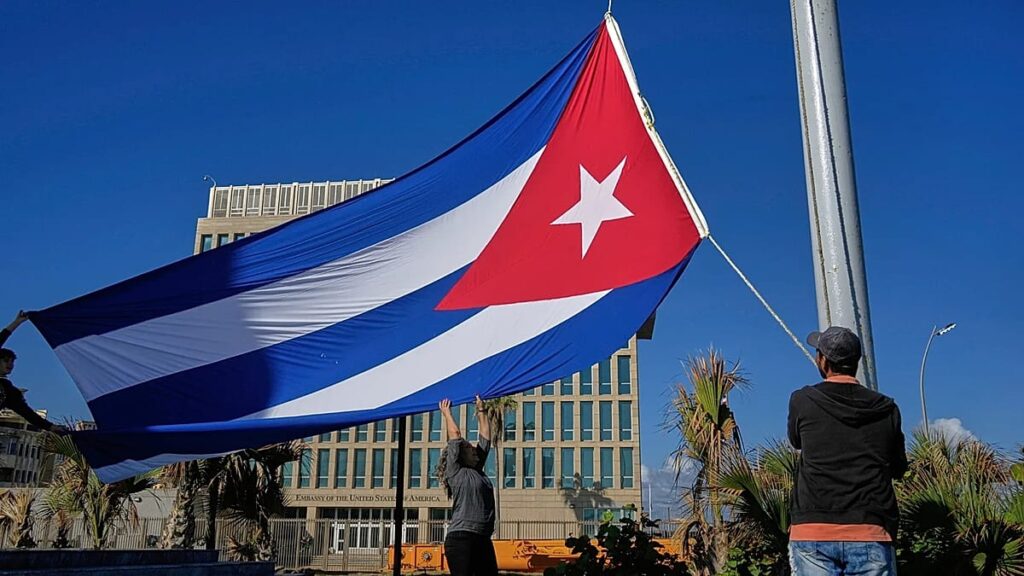

The presence of the Cuban military in Venezuela was just one example of the close cooperation between the two nations.

“Venezuela was Havana’s single most important political ally ever since Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro struck up their intimate friendship in the early 2000s,” Bert Hoffmann, a political scientist at the German Institute of Global and Area Studies, told Euronews.

As a presidential candidate in 1999, Chávez met with the leader of the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro, in Havana, and the two governments’ alliance has only deepened in the subsequent decades. Maduro was educated in Cuba and has positioned himself as the guardian of Chávez’s revolutionary leftist project; he has maintained close ties with Havana ever since coming to power.

Cuban officials hold key positions in Venezuela’s intelligence apparatus, and Havana has sent Caracas doctors and health care personnel in exchange for political support and cheap oil. Over the last several months, Venezuela shipped around 35,000 barrels daily to Cuba at a heavily subsidised price – and as Hoffmann told Euronews, Venezuelan oil deliveries are still the island’s crucial lifeline.

“Over the last months, Venezuelan oil still made up 70% of Cuba’s total oil imports, with Mexico and Russia sharing the rest,” he said. The fear in Havana is that the US could soon try to topple the Cuban regime without direct intervention by cutting it off from Venezuelan oil altogether.

Demise by decoupling

“While Washington will be wary of military action with ‘boots on the ground, the navy ships along the Venezuelan coastline can enforce an oil embargo at little cost,” Hoffann said. “And whatever the new Caracas leadership’s negotiating power is, continued support for Cuba will hardly be its top priority.”

While Cuba could seek alternative supplies from Russia, Iran, or Arab countries, helping out Havana directly would make any new supplier a potential target of US reprisals. And even if Havana is able to find some alternative source of oil, the already precarious living conditions Cubans are experiencing are set to decline further.

Cuba is already experiencing its deepest economic crisis in recent history. The country’s economy has shrunk by around 4% in the last years, with a contraction of 1.5% in 2025 alone. With inflation over 20%, food, medicines, and fuel shortages are widespread.

“Economically, Cuba now also pays a heavy price for having concentrated all investment on tourism, an industry for which the dire situation of crisis and political uncertainty is toxic,” Hoffmann said.

Meanwhile, removing, undermining or at least isolating Cuba’s communist regime one way or another has been an American priority since the Cuban Revolution in 1959, and for the Trump administration, the dire situation and Maduro’s forceful departure mean a window of opportunity for regime change.

“Cuba looks like it’s ready to fall. I don’t know if they’re going to hold out,” Trump said on Sunday on board Air Force One.

What next?

Yet according to Hoffmann, despite the events in Venezuela, the leadership in Havana has so far shown no sign of disintegration.

“The fear of what is to come after an eventual regime collapse is a powerful glue for elite cohesion,” he said. “They will closely watch how the post-Maduro elite survive the storm, or whether they will be hanged from the streetlamps.”

According to US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who was raised in Miami by Cuban exile parents, the Cuban elite should not be complacent.

“If I lived in Havana and I was in the government, I’d be concerned at least a little bit,” he told NBC News over the weekend, though he refused to talk about US plans for Cuba in any detail.

One potential scenario is a complete naval blockade, for which the Cuban army is already prepared – and in Hoffman’s view, this would not bring the Cuban people to the streets.

“Even if living conditions become ever more precarious, this does not necessarily translate into rebellion,” he said. “Mobilising collective action not only requires shared discontent but also the belief that protest may lead to change.”

The military action against Maduro could in fact demobilise everyday Cubans, not motivate them.

“If its message is that it is up to the military to shoot it out and for the governments to negotiate their deals, for ordinary people, this is no time to take to the streets, but to duck and cover.”

Read the full article here