Graham Richardson and his wife Cheryl at their Ramsgate home ahead of his election as general secretary of the NSW branch of the Australian Labor Party, in 1976. Credit: Martin James Brannan

Labor branches across Australia were battlegrounds between the old and new guards when Richardson became general secretary in March 1976. The NSW party was in the doldrums. Out of power since 1965, Labor was being dragged under by the Whitlam government’s rout the year before. Neville Wran’s state election win the following May proved the elixir that turned NSW into the engine for Labor’s later long federal ascendancy under Hawke and Keating.

Richardson was made for the ’70s and ’80s, that blokey era when bare-faced cheek and ill-gotten money beat talent and ideology every time. He took Labor into office, state and federally, but all that power coupled with all the money the party snagged from West Australian and Sydney carpetbaggers made winning the main game.

His reign over the NSW ALP fostered branch stacking and sacrificed ideals to expediency. He had the chutzpah to call his 1994 biography Whatever It Takes and his life-long nickname “Richo” was easily converted into journalistic shorthand for amiable scallywag.

Richardson, pot-bellied but surprisingly light on his feet, was a legendary luncher. His lair-like wit was honed in the Sussex Street pubs and Chinatown restaurants. Over the years he refined it into a consummate style for media usage where charmingly told lies disguised a tangled nest of untruths.

Richardson’s flash personality belied a habitual tendency to make like the innocent bystander at critical moments in his career.

Among the close calls was a mysterious 1993 fire that destroyed a Sydney printing plant owned by the company Offset Alpine Printing Ltd that Richardson and others had invested in. The insurance payout to Richardson and fellow investors topped $52.3 million and investigations later revealed he’d secreted almost $1.5 million in Swiss accounts and neglected to inform the Australian Taxation Office.

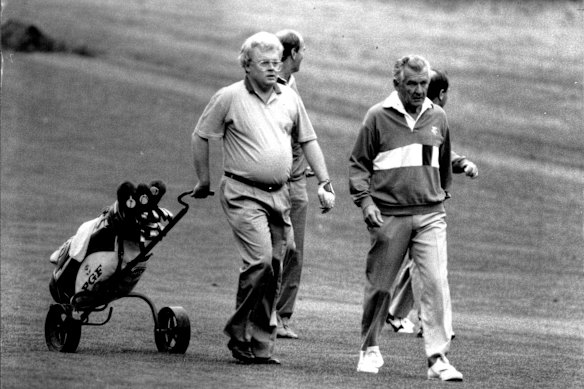

Then senator Graham Richardson (left) and prime minister Bob Hawke step out to the first hole while a minder and a driver survey the scenery.Credit: Peter Morris

In parliament, his penchant for risky business saw him resign from his close mate Keating’s ministry in 1992 after he’d used his political influence to (unsuccessfully) stop his cousin’s husband, and his mate, Gregory Symons from being jailed over a Marshall Islands immigration scam. Two years later, amid allegations he’d been using prostitutes on the Gold Coast supplied by a business associate of a man he had given a reference to on ministerial letterhead, Richardson left the Senate.

His knack for courting controversy undercut ministerial achievements.

Entering the Senate in 1983, Richardson was appointed by Hawke as minister for the environment and the arts in 1987, then given the additional responsibilities of sport, tourism and territories. Hawke later named him minister for social security. Richardson was credited with getting world heritage listing for the west tropics, establishing the Australian Sports Commission and duchessing both the Australian Democrats’ second preference vote and the support of young Greenie voters to give Hawke his unprecedented fourth election win in 1990.

But Hawke knew something was rotten and revealed at a briefing on the release of old cabinet papers in December 2015 that “my good friend Sir Peter Abeles had told me something about Graham that in my judgment precluded him from being in that position [the transport/communications portfolio]” after the 1990 election.

In March 1994, Richardson was sworn in alongside prime minister Paul Keating and fellow ministers Bill Hayden and John Faulkner at Government House.Credit: Andrew Taylor

“I knew that once I made the decision to refuse him what he wanted that he would turn his support and his very, very considerable influence with the NSW Right. And that’s what he did,” Hawke recalled, by way of explaining how Keating beat him in December 1991.

Keating rewarded Richardson, first with transport and communications, then health, and returned his old Hawke portfolios of environment, sport and territories.

Loading

After exiting the Senate in 1994, Richardson went to work for Kerry Packer, laboriously writing a weekly column in pencil for the Bulletin magazine and handing it over to a secretary for typing. With Keating still in office, Packer was mindful that Hawke/Keating had given him a $500 million windfall by allowing him to sell and then redeem the Nine Network (now owner of this masthead) and used Richardson as a useful conduit to the Labor government. When John Howard won government in 1996, Packer dumped Richardson and replaced him with Victorian Liberal powerbroker Michael Kroger. It was just business.

Before the 2000 Olympics, Richardson was given a job for the boys overseeing the failed Stadium Australia float – buying up 500,000 seats withheld from the public lottery. It had all the hallmarks of a fix, but Richardson walked away smelling of roses. His ALP mates even made him mayor of the Olympic Village.

The Sydney Olympics Organising Committee’s Michael Knight, Graham Richardson and Kevan Gosper leaving a press conference in 1999 after it was revealed that few prime Olympics tickets were made available to the Australian public. Credit: Andrew Taylor

In later years he became a television political commentator and a staple come election nights, and hosted Richo, an evening commentary program on Sky News, from 2011.

In April 2016, Richardson underwent a marathon 18-hour surgery to remove four organs, including his bowel, bladder, prostate, rectum and sciatic nerve, as part of his cancer treatment.

He battled cancer for years, but remained active in the media until as late as September this year.

Richardson died at 3.50am on Saturday, November 8, following weeks of influenza and pneumonia, his wife and son told 2GB Breakfast host Ben Fordham, who announced the news on air.

He is survived by his wife, Amanda Thompson, their son D’Arcy, and a son and daughter from his first marriage, Matthew and Kate.

Read the full article here