His personal injury law firm did $2 billion in revenue last year and his business empire includes a crime museum with O. J. Simpson’s white Bronco.

By Brandon Kochkodin, Forbes Staff

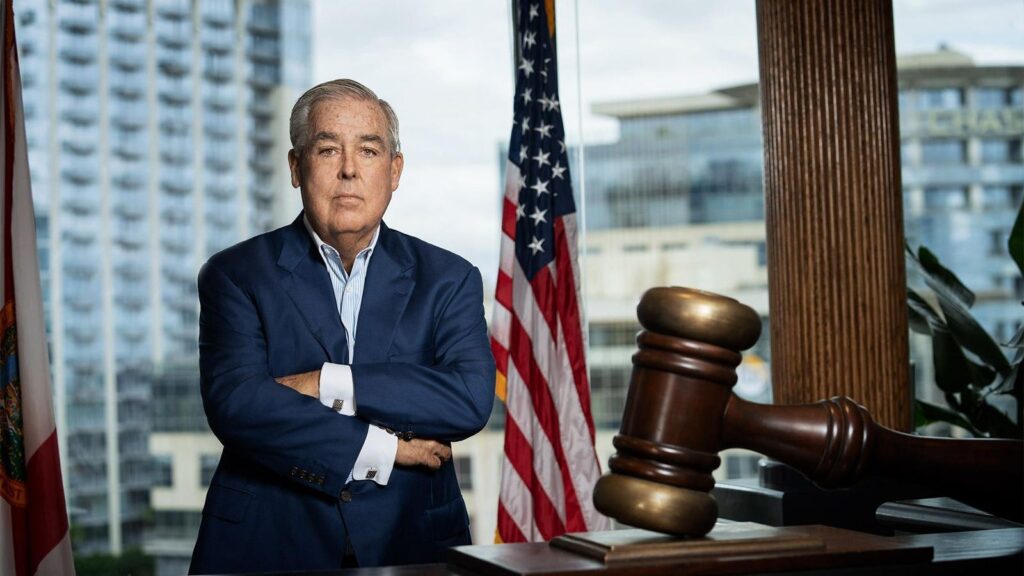

Despite the images on his over-the-top and omnipresent billboards, John Morgan isn’t an astronaut, swimsuit model, leather clad biker or Santa Claus. He’s a lawyer, self-made billionaire and the founder of Orlando, Fla.-based Morgan & Morgan, the largest personal injury law firm in the U.S., with more than 1,000 lawyers (and 6,000 employees total) across all 50 states. Last year the firm generated just over $2 billion in revenue and is now growing fast, on the back of $350 million in annual marketing spending (heavy on cable TV as well as highway and digital ads) and a recent push into big cities like New York, Philadelphia, Washington D.C. and Las Vegas.

Naysayers (and some competitors) still like to dismiss Morgan, 68, as an “ambulance chaser” or a “TV lawyer.” But between his advertising and political activism (he’s poured $14 million into getting Florida to raise its minimum wage and legalize medical marijuana), he’s earned enough goodwill that opposing counsel sometimes files a motion to keep jurors from knowing Morgan’s firm is involved in a case. In high-stakes trials, he gets around that by showing up in person—a tactic that once caused Home Depot’s lawyers to protest his presence.

“They can’t keep me from showing up,” Morgan declares. The tactic works because Morgan might be the most recognizable lawyer since Johnnie Cochran. (Morgan helped Cochrane start his own national firm, advised him on marketing and served as a pallbearer at his 2005 funeral.)

Make no mistake. Morgan & Morgan isn’t your typical legal firm with ownership widely distributed among unrelated partners. It’s more of a family business (they advertise that too). Morgan’s wife Ultima (they met in law school 43 years ago) and their three attorney sons are all partners and the family owns around 50% of the firm, with about 140 equity partners owning the rest.

We estimate the whole firm is now worth a minimum of $2 billion, based on its revenues and unusual brand value. But that’s just a part of Morgan’s wealth. One big payday came last year, when Bessemer Venture Partners paid $300 million for 60% of Litify, a legal software platform Morgan co-founded in 2016. Morgan says his family received less than half of that and all the after-tax proceeds they did receive went to his kids.

That makes Morgan one of just a few lawyers in the country’s history to become a billionaire strictly through legal ventures, as opposed to, say, buying a sports franchise. The most famous billionaire barrister was Texas tort king Joe Jamail, who made Forbes’ list of the 400 richest Americans repeatedly before his death in 2015.

But there’s more to Morgan’s wealth than the law–he’s got an eclectic, debt-free assortment of holdings ranging from real estate, to six indoor wacky WonderWorks science museums to a stake in the late Jimmy Buffett’s Margaritaville. WonderWorks alone throws off $33 million a year in EBITDA, making it worth, by our estimate, at least $150 million. (Forbes estimates Morgan owns about half of WonderWorks.)

Morgan’s latest hobby turned business is the Alcatraz East Crime Museum in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, where you can check out O.J. Simpson’s infamous white Bronco and serial-killer Ted Bundy’s Volkswagen Beetle. It’s already making him $5 million a year and he’s planning to build another crime museum too, to display more of what he describes as a “whole warehouse” of memorabilia.

All told, Forbes estimates Morgan and his family are worth at least $1.5 billion. Asked if he’s a billionaire, Morgan points out he’s been putting assets in his four kids’ names for years. “I’d be a billionaire easily if I had all their stuff,’’ he says. As for his personal net worth statement, Morgan says he values everything at what it cost him to buy or to build, not what it’s likely worth today. Given that he doesn’t take on debt, he explains, he’s got no incentive to puff it up.

Morgan also takes pains to dismiss any suggestion he lives or spends like a billionaire. “The truth of the matter is, I don’t live like I earn. All our homes are paid for. It’s probably two million a year that I live on. And that’s taking care of seven houses. Most of the money I live on is spent on paying the HOA, gardeners, and [stuff] like that. I don’t live extravagantly.”

John Morgan wears his humble roots proudly, as a source of his drive and, as part of his appeal to his everyday Joe clients. He was born in Kentucky to parents who struggled, he says, with alcohol and keeping the lights on. The family moved to Central Florida when he was 14. As the eldest of five children, Morgan became a surrogate parent and took on every odd job he could—paperboy, poinsettia salesman, Yellow Pages hawker. He even worked in costume at Disney World, starting as Fiddler Pig and King Louie before being promoted to Pluto, a role he earned, he says, because he could dance.

Morgan’s brother Tim also worked at Disney, lifeguarding at the Polynesian Village Resort’s pool. One day, a girl went missing. As Tim dove in to search, he struck a table hidden beneath the water’s surface. The impact left him paralyzed, with a C6 and C7 spinal cord injury. As Morgan talks about Tim, who passed away in July at the age of 65, his eyes start to water, and his voice slows, heavy with grief. He remembers how Disney “fought Tim like he was the Taliban” when his brother sought benefits after the accident. (Disney didn’t respond to our requests for comment.)

Enraged, he told his family, “I didn’t know what a personal injury lawyer was. But I know what I’m going to be.”

After graduating from the University of Florida’s law school in 1982, Morgan started out at a small firm. He quickly decided he was underpaid and in 1985 teamed up with other young lawyers to start their own firm.

The Supreme Court had blessed lawyer advertising back in 1977, but at their new firm, Morgan’s partners balked at how far he wanted to push the advertising envelope. So he left in 1988 to start Morgan, Colling & Gilbert, his current firm. “The (advertising) train was leaving the station,” Morgan told his wife, and a firm that jumped on early could become like “Kleenex”—a brand so popular, its name is synonymous with the product itself. (The firm was renamed Morgan & Morgan in 2005, after John Morgan bought out his original non-family partners, when they disagreed with his ambitious growth plans.)

The advertising worked—the firm got so many calls that John’s brother Tim set up a call center in 1993 to handle the hundreds, then thousands, of calls they received each day. Even with the phones ringing off the hook, Morgan felt something was missing: a superstar litigator to complement his own business and marketing flair. He started courting Keith Mitnik, a renowned Florida plaintiff’s attorney, taking him out for steak once a year. Finally, in 1997, after four years, Mitnik caved. “I watched him grow and grow, and finally I shut down my place and came over here,” says Mitnik, now 65. “I tell people I have one regret: I should have done it four years earlier.”

It was a win for both of them. Since joining, Mitnik has helped secure more than $130 million in judgments against R.J. Reynolds alone while taking on high profile cases like representing the Backstreet Boys in a lawsuit against their former manager, convicted Ponzi schemer Lou Pearlman. His reputation gave Morgan the credibility to attract more top talent. “Keith was already a legend,” Morgan says. “He was getting big verdicts everywhere, and now he was here.”

Thanks in part to Mitnik, the firm has gotten into large-scale class action lawsuits. It’s among the law firms that recovered a combined $750 million in data breach cases against Equifax, Capital One, Yahoo!, and the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (Morgan & Morgan served on the plaintiff steering committee); $13.5 billion of settlements in 2023 in water contamination cases against 3M (it was co-lead counsel) and DuPont in Stuart, Florida; and a $1.8 billion settlement in 2021 from Southern California Gas over a methane leak.

Fees in class actions are set by the judge and split among multiple law firms. So personal injury, with its hefty 30 to 40% contingency fees, remains Morgan and Morgan’s bread and butter. All told, it’s logged $22 billion in awards since founding. In 2023, for example, the firm’s biggest individual win came from a commercial auto accident, where a tractor trailer slammed into a client’s parked semi-truck on the side of Route 30 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, resulting in a $26 million award. It also gets revenue from cases referred to other law firms.

Thanks to its ubiquitous and John Morgan-centric advertising, people across the country sometimes think Morgan & Morgan is a local firm–an illusion that rankles competitors. In 2018, Philadelphia lawyer Jeffrey Rosenbaum sued claiming Morgan’s ads were misleading since the firm simply referred cases to local lawyers and Morgan himself wasn’t licensed in the state. Morgan hired a local staff attorney and the case settled, though Rosenbaum put up his own billboard along I-95, labeling himself the “real Philly lawyer.”

Not that Morgan—who once put up a billboard of himself flipping the middle finger—cares what other lawyers think. “Everybody is a capitalist until somebody wants to compete,” Morgan says. “Wherever I go, they all have a stick up their ass.”

As the big judgments have rolled in, Morgan has cemented himself as a political power player. He’s been a mega-donor and bundler for Democrats—he’s contributed millions since the 1980’s and raised $800,000 for President Biden’s 2024 campaign before Vice President Kamala Harris replaced him on the top of the ticket. When that happened, Morgan told the Democrats he wasn’t interested in doing more. Pictures in his office show him with the Bidens, Clintons, and Obamas. He’s teased a run for Florida governor for most of the last decade—partly, he admits, because it’s free advertising. But it’s complicated since he became a registered independent in 2017, after, he says, “they started putting the word socialist next to Democrat.”

Meanwhile, in what he brands “political philanthropy,” Morgan has poured his money and influence into specific issues. In 2020, he spent $6 million to pass a state constitutional amendment raising Florida’s minimum wage by steps to $15 per hour in 2026 (it’s now $13, the highest in the Southeast). At the time, Morgan faced criticism for outsourcing his firm’s call center work to companies paying less than $15. In 2016, inspired by how medical marijuana helped his brother Tim manage his pain, he spent $8 million on getting Florida to legalize it. He and Tim crisscrossed Florida in a bus, earning Morgan the nickname “Pot Daddy” along the way. He says he now takes a marijuana gummy every night before bed. Morgan didn’t finance the November 2024 referendum that failed to legalize recreational marijuana too, but was vocal in his support for it.

For Morgan, it’s not just about winning, but changing the game. He and Ultima contributed $1 million to help build the Morgan & Morgan Home, a 120-bed shelter for victims of domestic abuse with two bulletproof safe rooms, and $2 million to Second Harvest Food Bank of Central Florida, where the 100,000 square-foot facility now bears the name Morgan & Morgan Hunger Relief Center. And there’s more to come—Morgan plans to leave his estate (which he hopes will exceed $1 billion) to charity. (Remember, he’s been doing transfers to his kids all along.)

“Being poor, helpless, hopeless, and powerless, that’s a problem,” he says. “But the good thing is the taste never leaves your mouth.”

Morgan doesn’t spend much time in the office these days. He prefers winters in Maui, where he says his ashes will be scattered someday, and summers in New Hampshire. So when he does show up at the firm’s downtown Orlando headquarters, there’s a lot of gawking–what he calls “the panda effect.”

Inside his office, there are no pandas in sight, just giraffes–three golden giraffe statues stand guard on his desk and a cluster of stuffed ones huddle in the corner. Morgan explains he wants to buy a farm in Florida, stock it with giraffes and elephants, and “treat them like royalty.” He’s already scouted property in New Smyrna Beach for his personal game reserve. But his wife isn’t thrilled with the idea. To cool his obsession, she buys him giraffe tchotchkes, a kind of “here, you’ve got them already, now let it go” ploy. But letting things go just isn’t Morgan’s style. After our interview wraps up, he walks me to the elevator. He plans to ride down to the ground floor when one of his employees quickly sticks her arm between the closing doors to stop us. She tells him there’s a group waiting to discuss a big case involving Publix, the Florida-based grocer with $57 billion in annual revenue.

“Nice talking to you,” he says to me, reaching out for a goodbye handshake. Then, with a grin, he adds, “But Publix has money.”

Read the full article here