There are currently no regulations governing online or informal sperm donation, which is growing in popularity due to the cost of accessing fertility clinics and lengthy delays in getting treatment because of sperm shortages.

While men who donate sperm to IVF clinics in Victoria must comply with a 10-family limit, there are no rules governing how many families online sperm donors can contribute to.

Professor Catherine Mills, a bioethics expert at Monash University, said informal or online donors should be included in the state’s existing donor registry (which records egg and sperm donations to fertility clinics) to enable people to track how many families a donor has contributed to.

“Online sperm donation requires people to trust strangers with a decision that has lifelong consequences,” she said.

“Being donor-conceived is a lifelong condition. That is an enormous decision to put into the hands of strangers. It is a decision that needs a lot of regulation and support to prevent exploitative practices.”

Loading

She said it could be confronting for donor-conceived children to find out they had a multitude of half-siblings.

“They find it very important to be able to make contact with their biological progenitor or parent. Knowing that kind of origin story for one can be a really vital thing in terms of creating your own self-identity.”

Mills welcomed the state government’s investment in public IVF, but said persistent sperm and egg shortages were leading to lengthy delays that drove people to online donors. She said a lack of diversity among donors was also driving people online to find donors of the same ethnic background.

Fertility lawyer Stephen Page, who also sits on the board of the Fertility Society of Australia and New Zealand, described the online world of sperm donation as the “Wild West” and called for it to be regulated.

“Stories like this – with the trauma meted out to women and children – will keep occurring until politicians bite the bullet and regulate donor apps and websites,” he said.

He would like to see caps on the number of families to whom informal donors can contribute, a national voluntary register for all donors, and for apps and websites to be required to verify the identity of donors and provide this information to authorities.

“There would be a central register that could check state registers and find out whether he has been producing children left, right and centre,” he said. He said donors who surpassed family limits would then be removed from sites.

“I’m not opposed to the idea of meeting others online, but it should be done with a sense of autonomy and regulated freedom.”

Alisha Burns, who runs courses to help women decide whether to become solo mothers by choice, is also calling for a national register of all sperm donations.

She said this would allow donor-conceived children to connect with their half-siblings.

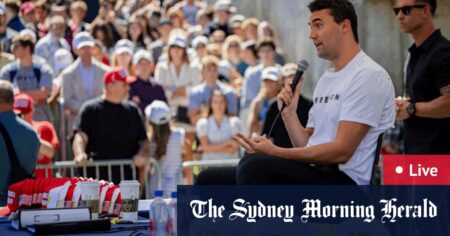

Adam Hooper is a sperm donor and runs popular Facebook group Sperm Donation Australia.Credit: Trevor Collens

Burns said many people were not educated about the pros and cons of sperm donation outside of fertility clinics, and she advises women completing her courses to never have sex with their donors.

“It changes everything,” she said. “If you have sex, they have parental rights to the child.”

Adam Hooper, who runs the Sperm Donation Australia page on Facebook, questions whether authorities would ever be able to effectively regulate online sperm donation.

“I just think it’s a costly exercise to the taxpayers of Australia for something they have never managed to get right in a regulated environment,” he said.

He advises people to pick a donor who links all recipients together from the start and to pick donors who have done ancestry DNA testing. He also advises donors to be transparent about how many families they have donated to.

He said Sperm Donation Australia managed its own voluntary donor register, and women could request information about how many families donors had already contributed to before proceeding with insemination.

The three-month review of Australia’s fertility sector will consider whether a national regulator is needed to replace state-based regulators. After the announcement of the review in June, Victorian Health Minister Mary-Anne Thomas said fertility industry self-accreditation and licensing under the Reproductive Technology Accreditation Committee was not working.

“It simply doesn’t pass the pub test that the people that provide the service are also the ones that determine who provides the service,” she said.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Read the full article here