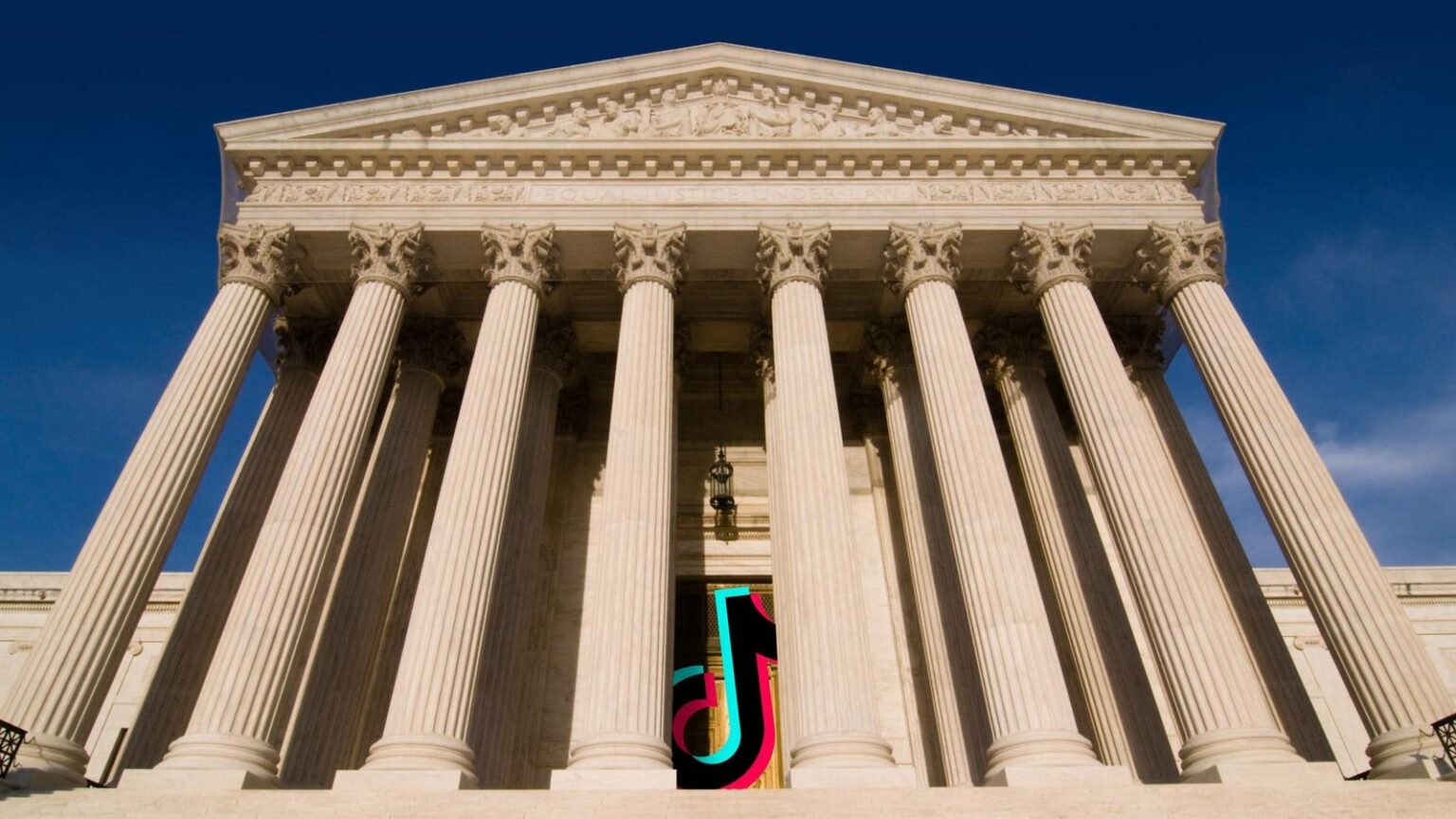

At the Supreme Court argument, the justices homed in on one key question: Can Congress ban a speech platform to stop the Chinese government from manipulating it?

By Emily Baker-White, Forbes Staff

When Congress passed the law that required TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, to sell it or see it banned in the U.S., it was partially motivated by the fear that the Chinese government might use TikTok to contort Americans’ discourse, pitting people against one another and eroding their trust in the democratic systems that define American politics.

On Friday, at the oral argument that will determine TikTok’s fate, Chief Justice John Roberts made a joke underlining this risk: “Did I understand you to say, a few minutes ago, that one problem is that ByteDance might be, through TikTok, trying to get Americans to argue with each other?” He then answered his own question, spurring laughter from the crowd: “If they do, I’d say they’re winning!”

Foreign governments, including China’s, have long run influence operations to try to divide and propagandize American citizens, and have used social media platforms to do so. (The U.S. government has run similar campaigns abroad, too.) But the TikTok law is the first attempt by the U.S. Congress to directly regulate a social media platform for the purpose of limiting those influence operations. This raises a key First Amendment question: Can the U.S. government, in trying to stop other governments from manipulating speech, itself manipulate speech by forcing the shutdown of a massively popular platform?

The whole idea of the U.S. government fighting foreign speech manipulation is “at war with the First Amendment,” argued Noel Francisco, counsel for ByteDance, on Friday. But the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed with that argument last month, in a controversial ruling that said sometimes, limitations on Americans’ speech are necessary to ensure a healthy free speech ecosystem. “[T]he Government acted solely to protect” Americans’ First Amendment freedoms, the D.C. circuit held — even as it upheld a law that might lead to the shutdown of a massive speech platform.

Today, a small handful of tech companies hold immense power over the information that Americans consume. In the NetChoice Cases last term, the Supreme Court held that American tech giants have a First Amendment right to curate that content — to promote some messages over other messages – as they wish. But foreign tech giants do not have that right, and in passing the TikTok law, Congress said that at least when those foreign companies are controlled by foreign adversaries, the same editorial control that is protected speech when done by an American company is a national security risk when done by a Chinese (or Russian or Iranian) one.

This tension leaves social media users with little transparency about why they see the messages they do, and which governments might have pressured them to promote or demote certain narratives. Just this week, Meta announced staggering changes to its content policies in an effort to curry favor with the incoming Trump Administration. But because Meta is a domestic firm acting of its own accord, it was just exercising its free speech rights. (In a previous life I held content policy positions at Facebook and Spotify.)

The TikTok bill is not a direct ban: it gives ByteDance the choice to sell TikTok instead of seeing it banned. But ByteDance, at least thus far, has insisted that it will not sell TikTok; instead, it will leave the U.S. market altogether.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett pressed this point during arguments, noting that TikTok will only be banned if ByteDance chooses a ban over a sale. But practically, ByteDance may not have much of a choice at all, because the Chinese government has said it is not allowed to sell TikTok, and flouting the Chinese government could endanger both ByteDance’s business and its employees’ personal safety.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar compared the case to a game of chicken between the Chinese and U.S. governments, and urged them not to let the U.S. blink first. Clearly, ByteDance does not want to sell TikTok, and it won’t do so unless it has no other option. Prelogar urged the justices to let the law go into effect on January 19, causing a temporary shutdown of TikTok in the U.S. There would be “nothing permanent or irrevocable” about such a ban, she said — it could be lifted as soon as a divestment is complete, and it might provide a “jolt” to ByteDance that would make it take seriously the possibility of a sale.

If the law does go into effect, TikTok will likely not only disappear from the app stores, but will also stop working in the United States. That’s because the law would require all the U.S. companies that help keep TikTok online, from cloud companies hosting TikTok’s data to content delivery networks and their providers, to stop doing so.

There are three ways the justices could stop the law from going into effect on January 19. They could rule for TikTok, and find that the law is unconstitutional, or they could issue one of two types of stays, temporarily stopping the law from going into effect while they deliberate on its fate. To grant the first type of stay, called a temporary restraining order, the court would need to find that ByteDance and TikTok are likely to eventually win their case. But the second type of stay, an administrative stay, would not require the court to take a position on the merits. Instead, it would just reflect the court’s decision that they need more time to consider the case.

The court is widely expected to rule on the case extremely quickly, before the January 19 deadline. If it upholds the law, TikTok will at least temporarily go offline — though President Trump could try to bring it back by issuing a one-time, three-month extension to give the company time to negotiate a sale.

Still, if the law is upheld, a three-month extension will likely not make a significant difference in TikTok’s future. Unless the justices invalidate the law, ByteDance will have to sell TikTok, or the platform will disappear in the United States.

Read the full article here