Antonio Guseli was a long way from home in a wild and isolated frontier when he stepped onto a platform at the top of the deepest shaft in Australia’s Snowy Mountains on April 16, 1958.

Plunging more than 300 metres from beneath the high alpine town of Cabramurra, it was also one of the deepest, dizziest lift shafts in the world.

With Guseli, aged 27, were three other young Italian migrants: Benito Pizzol, Giuseppe Rugolo and Michele Di Salvio. Their job that day was to jockey down the shaft a four-tonne concrete pipe attached below their platform.

It was part of the works that would siphon Snowy water through long tunnels to spin the turbines of a hydroelectric power station in the valley below known as Tumut 1.

They called for a lift operator to lower their platform a few inches, which itself weighed more than a tonne.

Without warning, a cog wheel on the hoist shattered into nine pieces. The cable holding the platform whirled free.

A Cooma detective, William Holes, reported to a coroner later that when the cog wheel broke, the emergency brakes on the hoist no longer worked.

The platform with the men aboard hurtled into the abyss, smashing into pipes set 85 metres below. Antonio Guseli and his three workmates were killed.

Investigations showed that unseen beneath a layer of grease, a faulty weld apparently ignored by the contractor gave away. The coroner held no one culpable.

The death of four men in a split second was the worst single workplace accident in all the 25 years of construction of what remains among the largest engineering projects in modern history: the Snowy Mountains Hydro Scheme.

Death, however, was far from uncommon.

The official figure for workers who died building the hydro scheme, often in horrendous circumstances, is 121.

Their names are engraved on a large monument in Cooma that was finally built by the federal government and the Snowy Hydroelectric Authority in 1981. High-level wrangling made it clear some officials were initially reluctant to mention victims of the grand hydro scheme at all.

Irish-Australian historian Siobhan McHugh mentions in her marvellous, award-winning book, Snowy – A History, that the man who became Snowy Hydroelectric Authority’s second commissioner, Howard Dann, was against focusing “undesirable attention” on the dead. The federal minister responsible for the authority in the late 1960s, David Fairbairn, said it was “difficult to justify expenditure on a memorial or plaque”.

The authority’s official reports weren’t exactly forthcoming, either.

In 1958, the year the four Italians were killed in Tumut 1 lift shaft, a total of 12 men died in ghastly accidents, bringing the total to 42 of those who had died since the first in 1952.

Yet, the ninth annual report by the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectricity Authority, which covered 1958, did not mention a single fatality among the workers. It reported in satisfied terms about progress on the Tumut 1 power station, including work on the shaft in which the Italian men died, without any reference to the accident.

The same report’s section on “Staff and Industrial Matters” also managed to overlook entirely deaths in the mountains, but expressed as “a matter of deep regret” the death of a senior executive, chief civil engineer Ira B. Hughes.

We know this because Tony Guseli, a nephew and namesake of the Antonio Guseli who died in the Tumut 1 lift shaft, has taken the trouble to compile a small mountain of archival material related to the deaths on the Snowy Mountains scheme.

Guseli, of Shepparton, whose father worked on the Snowy, too, but died later in an industrial accident in Italy, has dedicated much of his time since stepping aside from his building business to granting lasting identities to the 29 Italians who died.

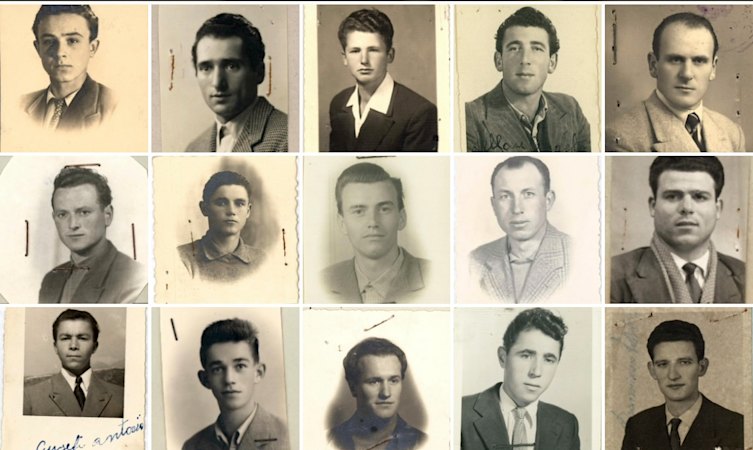

He has put together a haunting collage of photographs of all but two of them.

Here are the faces of young men who fled crushing poverty, filled with hope that there might be a better life in a land that was a mystery to them, and who sent home money to help support the families they would never see again.

Among the documents Guseli has gathered are inquest reports, probate records and migration and employee papers from deep in the NSW and National Archives.

His purpose is simple.

He believes his uncle and all the others who died on the Snowy Hydro Scheme deserve more respectful recognition than simple names on a monument. He has found that a number of the names on the memorial are misspelled.

He acknowledges the Snowy Scheme Museum in Adaminaby has done much to celebrate the legacy and stories of workers on the Snowy, but believes there is more to be told.

This year, he plans to widen his own research beyond the Italians to those from numerous other nations who perished. Apart from the 30 Australian men who died, most had no relatives in Australia.

The death roll includes men from countries in what was then called Yugoslavia, from Ireland, the UK, Greece, Germany, Norway, Poland, Spain, Austria, Hungary, Holland, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Romania, Switzerland and the Baltic States – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

Who, Guseli wonders, even knows where many of their bodies lie?

Only four of the 29 Italians who died were taken home to be buried in Italy, he discovered.

He has established there are 16 Italians victims of the Snowy buried in Cooma cemetery, and suspects some of their graves may never have received a visit from a direct relative.

Guseli has pledged to make available all the documents he has gathered to the relatives of Snowy workers killed on the job.

Death came in hideous ways.

Many died in tunnels when rocks or scaffolding fell on them or small locomotives or trucks ran over them, or when gelignite exploded at the wrong moment. Some of the men were electrocuted. A lightning bolt sizzled 100 metres into a tunnel at Guthega and set off explosives, killing a worker.

Others crashed over mountain sides in trucks and big earth-moving machines.

Among the most horrendous deaths was that of a Yugoslav trapped to the waist in fast-drying concrete in a shaft within a dam site at a place called Island Bend. His mates poured sugar into the concrete in a desperate attempt to slow it from setting.

No one who was there that day, December 21, 1963, could ever forget it. The man took two hours to die, according to records and recordings gathered by Siobhan McHugh.

Altogether three men died in that single concrete spill – two from what was then called Yugoslavia, and one Spaniard.

The achievements of the Snowy Mountains Scheme, of course, remain monumental. Eight power stations were created to store and supply vast amounts of electrical power. They were fed by water from 16 major dams through 80 kilometres of aqueducts and 145 kilometres of tunnels carved through the mountains.

The Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers were transformed into relatively reliable suppliers of irrigation for the nation’s food bowl – though at heavy environmental cost, including the loss of what had been the mighty Snowy River’s journey through Gippsland to the sea.

The multicultural nature of those who worked on the Snowy scheme from 1949 to 1974 also contributed mightily to the new Australia that emerged in the decades after World War II.

Today, there are many hundreds of thousands of Australians who are descended from the mostly young men from war-shattered nations and displaced persons camps across Europe who gambled on new lives in Australia.

The Snowy scheme needed 100,000 workers, and Australia in the late 1940s and ’50s had a population of only about 8 million.

All but cut off from the world in rough camps dotted around the mountains, the workers from far away laboured and played hard.

Teams of tunnellers, mad keen on winning bonuses and glory, competed against each other to blast their way deeper and further than safety should have decreed.

Some of them blew their pay cheques at the gambling schools that flourished in the camps and in Cooma.

Unofficially sanctioned pimps brought caravans and teams of prostitutes from Sydney and Melbourne, and men formed queues, cash at the ready.

A big country-raised policeman named Beverly Wales took it upon himself to enforce order. Heading towards the highest, reputedly roughest camp in the mountains, a place called Happy Jack’s, legend has it he stopped off at a wet canteen to announce himself. If anyone wanted to oppose him, he announced, they better do it now. Four big Australians took up the offer. Wales laid them all out. Perhaps he was overcompensating for being named Beverly.

Bev Wales stayed 15 years in the mountains. In the 1980s, working in Albury as a reporter, I was assailed with reminiscences of his exploits. When he wanted to separate brawling workers, I was told, he simply wrapped his giant hands around each man’s neck and squeezed.

Most of the Snowy’s workers, however, saved and went on to build those new lives they had dreamed about when they left Europe.

But 121 never got the chance.

Tony Guseli refuses to allow their legacy to remain nothing more than names on a concrete monument.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Read the full article here