Running from $1 billion in debts and liabilities, Jim Justice may have constituents here and overseas who are more important to him than the people of West Virginia.

By Christopher Helman, Forbes Staff

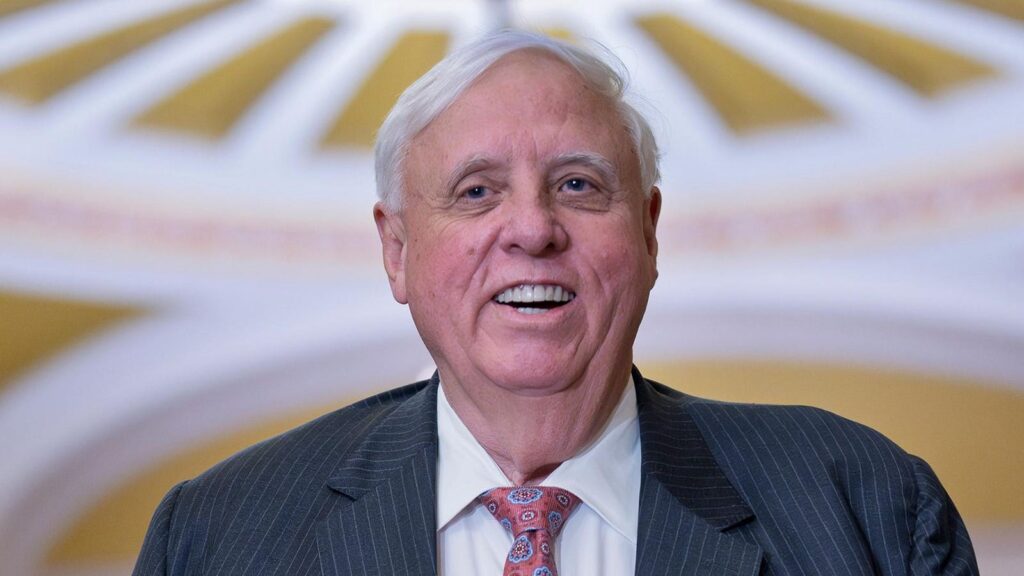

When West Virginia Governor James Conley Justice II finishes out his gubernatorial term in mid January and reports to Washington, D.C. to be sworn into the United States Senate, he will become one of the nation’s poorest senators.

How can that be? After all, for nearly a decade until 2021 Forbes figured Justice to be a billionaire, the richest man in the Mountain State, thanks to a lifetime amassing a fortune in coal and real estate with gems like the historic, 710-room Greenbrier resort in West Virginia’s Allegheny Mountains, with its golf course that has hosted the annual LIV Golf tournament.

But a closer look at Justice’s finances reveals that his empire is severely troubled. The Greenbrier, for example, is suffering from years of neglect and may now be worth less than half the $1 billion value Justice long claimed. Justice’s coal companies, led by Bluestone Resources, still mine about 500,000 tons per year, but that is down from 2 million tons a decade ago. They likely generate $150 million in revenues and have an enterprise value less than $200 million.

Those are substantial assets, but Justice’s liabilities are much greater. According to Forbes estimates, Jim Justice is in hock to the tune of more than $1 billion, in the form of personally guaranteed bank loans, debt, court judgments and environmental liabilities. By Forbes reckoning the new Republican Senator from West Virginia has a net worth of less than zero.

Justice’s attorneys and spokespeople have not responded to Forbes’ repeated requests for comment.

Last year, it looked like Justice’ cash crunch was so severe that Greenbrier employees received notice from their health insurer that they were set to be dropped because the hotel hadn’t paid its share of premiums (it was later resolved).

Keeping an eye on every nickel is Justice’s most concerned creditor – publicly-traded Carter Bankshares of Martinsville, Virginia, a $4.6 billion (assets) community bank known as “the home of lifetime free checking.” Justice personally owes Carter some $375 million. The loans are secured by the first lien on the Greenbrier, and many other assets. When Justice defaulted on his payments in early 2024 Carter announced that it would hold a public auction of the resort, only calling off the auction in late June after Justice promised to at least make $2 million in monthly interest payments. So concerned is Carter over Justice’s debts that it has forced the liquidation of collateral – including thousands of acres auctioned in Greenbrier and Monroe counties, such as the 500-acre Kate’s Mountain tract.

Other creditors are coming for West Virginia’s 73-year-old freshman senator. Last January, Russia’s Caroleng Investments Limited, which is due $10 million in royalties on Justice’s coal mines, won a court order to seize the Justice family helicopter, which they sold for $1.4 million. In June a court ordered U.S. Marshals to help Caroleng seize enough assets from Justice family coal companies to cover the rest.

Then in October distressed debt investors McCormick 101 and Beltway Capital of Maryland also announced an auction of the Greenbrier, to collect a remaining $20 million they were owed of a $140 million promissory note on which Justice had defaulted.

How could Justice, having bought the Greenbrier out of bankruptcy for $20 million in 2009, now be at risk of losing it? Because over a long career of breaking contracts, defying court orders, slow-paying bills and paying old loans with new ones, Justice has worn out every lender he has dealt with. Coal industry executives disown him for being an untrustworthy counterparty. “Bills are optional and negotiable. He pays bills by waiting for people to sue,” says one senior coal executive, who requested anonymity.

And yet somehow Big Jim always manages to find another lifeline.

In the Greenbrier case, $49 billion New York City private equity firm Fortress Investment Group bought the $20 million defaulted loan (which is junior to Carter’s claims) and called off the resort’s auction. Fortress was cofounded in 1998, by billionaires Wes Edens, Mike Novogratz and others. In 2017, billionaire Masayoshi Son’s Softbank Vision Fund bought 90% of the Fortress for $3.3 billion. Softbank sold the stake in 2023 for about $3 billion to Mubadala Investment, the $300 billion sovereign wealth fund of the United Arab Emirates — making this oil rich Islamic monarchy one of Senator Justice’s most important benefactors.

“He owes these folks something, and all of a sudden we find out they are foreign nationals?” says Michael Pushkin, a member of the West Virginia House of Delegates and chair of the state Democratic party. “He’s going to be beholden to these folks.”

James Conley Justice II grew up in coal country. His father, James Sr., studied aeronautical engineering at Indiana’s Purdue University and was an Air Force captain during World War II. James Sr. co-founded Ranger Fuel to mine coal in the early 1960s and then sold it in 1969 for $70 million (about $600 million in today’s money) to Pittston, a Virginia-based mining concern. In 1971, Jim Sr formed Bluestone in the coal fields of West Virginia’s McDowell County. For two decades Bluestone produced 500,000 tons per year of what’s known as metallurgical or coking coal, a premium hard coal used to make steel.

Young Jim worked for his dad for decades. When his father died in 1993, he took over. A big payday came in 2009 when metallurgical coal prices jumped 40% to $140 a ton, and he sold his core coal mine assets to Russian company Mechel for about $450 million in cash and preferred stock.

Justice thought he had exited coal, but the Russians, hindered by falling coal prices, couldn’t make the assets work. In 2014 Mechel sued Justice for fraud, saying it sold them crummy mines. Justice countersued, saying Mechel just didn’t know how to operate them. In 2015 they settled, and Justice bought the company back for $5 million, plus assumed debt and the agreement to pay Mechel’s holding company a royalty of $3 per ton of coal mined from the assets in the future. Justice said last June that the Russians had turned the mines into “the godawfulest mess you’ve ever seen.” He needed fresh working capital to fix them.

Until 2017 Justice’s biggest source of bank loans had been Worth Carter. The founder of Carter Bank was known to extend funds liberally to Justice, often with insufficient documentation. As Justice claimed in a later suit against the bank: “Between Mr. Carter and Governor Justice, a word and a handshake sufficed.” When Worth died, Justice owed the bank $740 million, and new management, including current CEO Litz Van Dyke, moved to reduce exposure to the coal magnate (then a quarter of their total loan portfolio). So they cut Justice off.

The Justice companies sued the bank claiming (unsuccessfully) a “tortious and unlawful” scheme to undermine their businesses.

For new financing, Justice turned to upstart U.K.-based Greensill Capital, founded by Lex Greensill, who grew up on a farm in Queensland, Australia. Greensill had become a whiz at an aggressive form of supply-chain financing — essentially getting companies money upfront for what they referred to as “hypothetical invoices” and “projected receivables” from “prospective buyers” of their products.

In 2018, Greensill loaned Justice’s Bluestone Resources $850 million ($742 million after Greensill’s hefty fees) against future shipments of Appalachian coal as well as coke used in steelmaking. Bluestone made deals to sell shipments to another Greensill borrower, Indian-born British industrialist Sanjeev Gupta and his steelmaker GFG Alliance. After the pandemic hit, both Bluestone and Gupta defaulted on their contracts with each other as well as their loans to Greensill, which had already been packaged and sold to investment funds sponsored by Credit Suisse. (Those same funds were also exposed to convicted fraudster Bill Hwang’s pump-and-dump fund Archegos).

Ultimately the investment funds failed, as did Greensill. After UBS acquired Credit Suisse in 2023 for $3.2 billion, it disclosed in regulatory filings that as of 2022 Bluestone owed them $690 million, which was personally guaranteed by Justice and secured by coal mines the Justice family has now been trying to sell for two years. In late 2023 after Bluestone had paid back $48 million of its indebtedness, it asked for a “payment holiday.” According to UBS bank filings Bluestone remains in arrears.

What did Justice do with the $742 million he borrowed from Greensill? He handed $226 million of it over to Carter Bank to reduce his balance there (which Greensill liquidators tried unsuccessfully to get back, claiming fraudulent conveyance). He also bought more coal mines and spent millions to buy and restart a defunct plant in Birmingham, Alabama, which could process his coal into high-energy-content coke essential for steelmaking.

Bluestone was not an environmentally conscientious operator. In 2021, the Birmingham health department shut down the plant to halt the discharge of benzopyrene, barium, and other toxins into Five Mile Creek and the Black Warrior River. In 2022, Bluestone agreed to pay a $925,000 fine and signed a consent decree, but dragged out the payments. After Justice’s son Jay ignored an August 2024 order to appear before the court, federal district Judge R. David Proctor held him in contempt.

But Jim Justice has never let environmental issues stop him. Most recently, in 2023 the DOJ sued his companies for over $6 million in fines and cited more than 100 mining violations. Justice’s attorneys responded in court documents that the mining companies are essentially broke and the fines “have not been paid, in large part, because the companies have no ability to pay.” In Virginia a state report last year estimated his shuttered mines face $230 million in reclamation liabilities, far more than any other miner in the state.

Meanwhile, Justice still can’t shake the Russians. Caroleng Investments, the holding company for Mechel’s interests, won a $10 million judgement against Bluestone in U.S. district court in Delaware last year over the unpaid royalties it is owed. Judge Richard Andrews ordered the sale of subsidiary Bluestone Minerals to satisfy the judgement, but Justice is trying to block the sale, claiming it can’t be sold to benefit Caroleng because Credit Suisse/UBS has a stronger claim to the assets. Caroleng did succeed in forcing the sale this year of a Justice helicopter, for $1.4 million.

Another U.S. district court judge, Gregory van Tatenhove in Kentucky, wants to make sure that the Justices aren’t able to make their companies “judgement proof” — avoiding paying court-ordered judgements by fraudulently transferring cash from one subsidiary to another in a kind of shell game. This is apparently how their Kentucky Fuel subsidiary appears to be avoiding paying a roughly $18 million judgement tied to a coal contract dispute. In July 2024 Tatenhove found Jay Justice in contempt and is fining him $250 a day until he turns over financial documents. The judge wrote that continued mendacity would lead him to rule that all the Justice companies should be considered “alter egos” of Jim and Jay. This could potentially lead to a so-called “piercing of the corporate veil” – allowing Justice creditors to rummage around all the family’s many pockets looking for cash to seize.

Back at the Greenbrier, the big question is how long will the Justices be able to hold onto even nominal control of the resort with creditors constantly looking to liquidate its assets.

In November, for example, Hammond, La.-based First Guaranty Bank ($3.9 billion assets) said it planned to auction off a house owned by Jay Justice on the Greenbrier grounds — a first step in recouping more than $35 million the Justices’ borrowed from the bank in 2020. Jay bought the house in 2021 from NBA great Jerry West, who died last year.

The need to pay down debts to Carter Bank and others prevents the Justices from reinvesting any cash generated into sprucing up its rundown guestrooms and traffic-worn carpets. In 2020 the PGA canceled its annual tournament at the Greenbrier after spotty attendance at the 2019 event – when Justice’s Bluestone Resources tried to grow crowds by giving away 30,000 tickets. Greenbrier’s problems have been good for business at Omni Hotels’ Homestead Resort (owned by Dallas billionaire Robert Rowling), an hour away in Hot Springs, Va. In 2023 the Omni Homestead completed a $155 million renovation.

Will Justice’s new backers at Fortress Investment Group want to invest new money into the property even if Carter’s first lien claim benefits most? Fortress had no comment. Justice, in an October press conference said, “We’ve got a lot of stuff cooking and working with Fortress. They’re good people.”

For Greenbrier, money from Fortress could be lifesaver, especially if it pays off the outstanding Carter Bank debt and invests in sorely needed renovations and upgrades. Top tier destination hotels like Greenbrier, with its 710 “Signature” rooms, have recently fetched more than $1 million per room. A spokesperson for Mubadala (which ultimately answers to His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan) says, “Fortress operates independently with full autonomy over their investment decisions and Mubadala is not involved in their investments in any way.”

Now that Justice is headed to Washington with full-throated support for all of President-elect Trump 2.0’s policies, it’s unlikely that any of the Justice Family creditors with stakes in important assets like Greenbrier, will enforce any kind of “cramdown” against the debt-laden senator.

“I’ll support all his choices,” said Justice in November referring to Trump. This could include voting for the loosening of federal carbon dioxide regulations – which would be great for coal sales. So don’t be surprised to see Big Jim dig himself out of his current deep debt hole.

With reporting by Matt Durot.

Read the full article here