The federal government defended its actions, saying it had committed more than $130 million towards investigating the problem, arguing risks were being “appropriately managed”.

PFAS substances are better known as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down in the environment and are linked with cancer, high cholesterol and immune system dysfunction.

The investigation at Sydney Airport, which has been shrouded in secrecy, remains unfinished 17 years after it began.

It can be revealed the parties involved have come to blows over who is responsible for footing a clean-up bill that could soar to hundreds of millions of dollars.

This masthead revealed in 2018 that the airport is polluted by some of the highest PFAS concentrations ever seen in Australia.

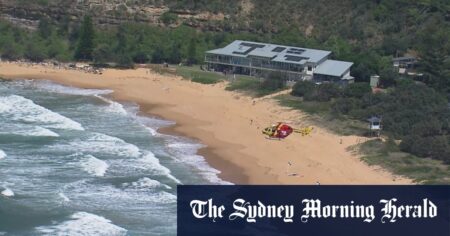

It is flanked by a small sandy beach that boasts unrivalled views of the main north-south runway.

While the strip’s official name is Commonwealth Beach, it is better known as “Planespotting Beach” or “Tower Beach” because it abuts an airport control tower.

It is frequented by families, horse riders, dog walkers, aviation enthusiasts and fishermen enjoying its calm waters under the shadow of jumbo jets touching down on the tarmac.

Prized group 1 thoroughbred racehorses also converge on the beach weekly for water training. Legendary racehorse Winx was photographed cooling off there in 2017.

Resident Terry Daly has been paddling and swimming with his children at Tower Beach for years.

He was stunned in early 2023 to see signs erected reading “no swimming, no fishing”.

Handlers regularly take top thoroughbred racehorses swimming at Tower Beach. Pictured are horses swimming at sunrise on Friday. Credit: Flavio Brancaleone

Daly took the matter up with local authorities in a bid to find out the reason for the ban, but had little luck with his initial inquiries at Bayside Council.

After “many months of persistence” Daly received correspondence from a Sydney Airport employee confirming the signs were due to concerns about PFAS contamination.

“The signage you refer to is located on Sydney Airport’s land and has been erected as a precautionary measure taking into account the NSW EPA’s ongoing investigations of PFAS use across the state including in the Botany Bay area,” the employee said.

The email, seen by this masthead, does not specify the source of the PFAS threat.

However, Tower Beach is less than 200 metres from one of several fire stations at Sydney Airport where PFAS chemicals were historically used or stored in firefighting foam.

The Herald put detailed questions to Sydney Airport Corporation this week seeking the results of any sampling of water and sand undertaken at Tower Beach and nearby swimming spots in Botany Bay.

Sydney Airport did not respond to questions regarding sampling. Nor would it comment when asked why the signs were not displayed prominently and whether potential risks to thoroughbred racehorses had been assessed. The corporation is a private company that holds the lease over the airport.

Daly was angered by the lack of transparency. He argued the community had the right to know the results of any sampling and what authorities planned to do to remediate the beach if the levels were unsafe.

“Tiny kids are playing on the sand there all the time,” he said.

Terry Daly swam regularly with his children at Tower Beach near Sydney Airport, until he discovered it was banned due to cancer-causing chemicals. Credit: Flavio Brancaleone

Daly was troubled that his children had swum at the beach and spent many weekends collecting rubbish there for their Duke of Edinburgh awards.

Daly said he had also seen high-profile horse trainers arriving with thoroughbreds in tow around the time of The Everest race for a post-training swim.

“I spooked one once paddling into the beach and one of the handlers got angry, saying ‘This is a $2 million horse,’ ” he recalled.

Racehorse Winx (left) is patted by strapper Umut Odemisloglu (centre) as she is ridden at Tower Beach in 2017. The beach is now closed to swimming due to toxic contamination in the area. Credit: Kate Geraghty

When the Herald visited on Monday, a toddler was drawing pictures in the sand. Six fishermen were scattered along the shoreline, and signs banning fishing were not visible where some of them were camped at the beach’s southern end.

Manuel Debrincat, who accompanied the fishermen, seemed surprised when asked if he would be willing to consume any of their catch.

“If it was a decent size you would,” he laughed. “We’ve already chucked a couple back.”

Debrincat was unaware of the fishing ban until he was informed about it by this masthead.

A trove of sensitive documents relating to PFAS was recently tabled to state parliament in response to a request by Greens MP Cate Faehrmann.

A fisherman at Tower Beach this week. Signs banning fishing were not visible from where he was standing at the southern end of the beach. Credit: Dominic Lorrimer

They provide a window into the growing angst within the NSW Environment Protection Authority about the pace of PFAS investigations at Sydney Airport.

In a December 2023 briefing note to Sharpe, the EPA said it had received “limited” reports about PFAS at Sydney Airport and further investigations would give it “a clearer understanding”.

The EPA was first alerted to the pollution in 2010 but has had no power to compel investigations because the airport is on Commonwealth land and regulated by the federal Department of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Development.

The EPA complained that it had historically received “minimal co-operation” from the department and had consistently raised concerns about its “lack of urgency” towards PFAS investigations.

Asked this week if its stance remained the same, a NSW EPA spokeswoman said it was continuing to urge the department to ensure remedial action was taken at Sydney Airport to protect the community from PFAS contamination.

“Transparency around the level of contamination is important to ensure community awareness,” she added.

The Department of Infrastructure oversees Airservices Australia, a Commonwealth agency in the firing line over PFAS contamination because it provides firefighting services at airports.

Loading

Last month in a submission to a Senate inquiry, Sydney Airport and hundreds of other airport operators across the country demanded Airservices Australia be held responsible for contamination at their sites.

“PFAS contamination at federally leased airports is a matter that must be addressed, particularly to protect the health and safety of workers, users of airports and the surrounding communities,” said the submission by the Australian Airports Association, which represents more than 340 airports and aerodromes nationally.

“Airports have been engaging with federal regulators for many years on PFAS contamination on airport sites. However, to date, progress from federal regulators has been lagging.”

The submission argued the “polluter pays” principle had been adopted at Defence bases polluted by PFAS but not at airports.

Loading

Sydney Airport previously accused the federal government of failing to ensure Airservices Australia is held to account.

“We remain concerned by the inaction of Airservices and lack of government response,” the airport’s sustainability report from 2022 said.

An Airservices Australia spokesman said it had not used foams containing PFAS at Sydney Airport since 2010, and its use of them beforehand was in line with international standards at the time.

“Airservices is currently conducting a detailed site investigation into the occurrence and extent of PFAS at, and associated with, our lease areas at Sydney Airport, he said.

Loading

“We expect reporting to be made available to relevant NSW agencies in mid-2025.”

The spokesperson did not answer directly when asked whether the agency accepted liability for the pollution or why investigation reports were not being made public.

He said the agency would continue to provide information to “relevant health and environmental agencies including the NSW EPA”.

A Department of Infrastructure spokesperson said the federal government had committed $130.5 million for PFAS investigations at civilian airports where the Commonwealth had historically provided firefighting services using foams containing PFAS.

“Airport participation in the program is voluntary and Sydney Airport is eligible to participate,” the spokesperson said.

The spokesperson said the department was working closely with Airservices on PFAS management activities at Sydney Airport to ensure that “any risks are being appropriately managed”.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Read the full article here