If a panel convened by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has its way, a health risk warning included in hormone treatments for symptoms of menopause may soon be removed.

On July 17, FDA Commissioner Martin Makary, a longtime proponent of estrogen and other menopause hormone treatments, hosted a panel of experts who oppose the so-called black box warning. Makary invited the panelists to “update us, teach us about the latest evidence, and help guide us as we think through what should be done here at the FDA.”

Since 2003, menopause hormone therapy medications have come with a black box warning of potential side effects. The warning states that the medication might increase the risk of strokes, blood clots, dementia and cancer, and it should not be used to prevent cardiovascular disease or dementia. These warnings are the highest level of advisory the FDA issues for medications, and they are used only for drugs that can cause serious or even life-threatening effects, like diabetes medications that can lead to heart attacks in patients with preexisting conditions.

The warning was instituted after a large study in 2002 suggested that menopause hormone pills containing estrogen and progestin could raise the risk of breast cancer, blood clots, stroke and heart disease.

But the warning is no longer applicable to the low-dose therapies used today and may be harming women who could benefit from the therapies, panelists said. They were most adamant about opposing the warning for estrogen that is delivered topically to the vagina; the risk data came from studies of a pill version of hormone replacement therapy, not the topical version. Some panelists said package inserts accompanying vaginal estrogen should include a lower-degree warning about vaginal bleeding and a recommendation for breast cancer survivors to consult their oncologist before using the treatment.

While the panel included only advocates of removing the warning, experts not affiliated with the panel also agree that the black box warning should be revisited. The warning has “superseded the evidence base,” says Irene Aninye, chief science officer of the Society for Women’s Health Research, a science, education and advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. The black box warning “tends to have more harm than benefit, especially for the low-dose estrogens.”

The Menopause Society supports removing the black box warning from vaginal estrogen products, says Monica Christmas, a gynecologist at the University of Chicago and associate medical director of the society. But removing the warning from pills, patches and other systemic estrogen treatments, which circulate in the blood through the whole body, is trickier. They may make bleeding in perimenopause worse or stimulate growth of estrogen-sensitive breast cancers, but improve many bothersome symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes or night sweats, she says.

Other experts say that Markary and some of the panelists overstated some of the benefits and downplayed some dangers of hormone therapies. FDA usually consults experts before approving drugs, but this was not one of the agency’s standing advisory committees. It’s unclear whether the panel discussion will bring about a shift in FDA policy concerning the menopause medications and when, but Makary promised the agency “would take a hard look at” removing the warning label from vaginal estrogen products. The decision may come soon. “We’re trying to move faster than the typical government process,” Makary said.

Here’s a closer look at some of the science behind hormone replacement therapy and what removing the black box warning could mean for women’s health.

Black box warnings on vaginal estrogen might not be supported by scientific evidence

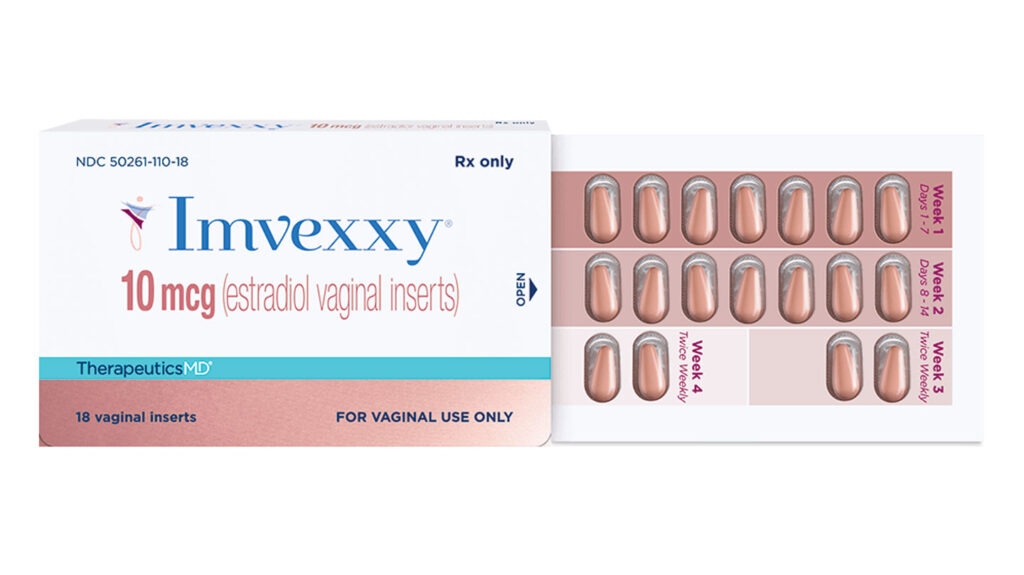

Vaginal menopause hormone therapy can come as a tablet, cream, gel or ring inserted into the vagina. This local application of estrogen can reduce menopause symptoms like vaginal itchiness or dryness and pain during sex. The treatments can also help prevent urinary tract infections, which increase after menopause.

These vaginal estrogen medications come with the same box label as the pills and patches that disperse estrogen systemically throughout the body. That’s because they all contain estrogen, so are treated the same. But there isn’t a lot of scientific evidence that supports lumping these two therapies together.

To cause the side effects listed in the label, such as strokes and blood clots, vaginal estrogen would have to get into the bloodstream and then travel to the brain, lungs, breasts and other organs, said James Simon, an ob-gyn at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., who was one of the FDA panelists. “It just doesn’t do that,” he said. Many studies have shown that vaginal estrogen, especially when used in low doses, bumps up estrogen blood levels by only a small amount.

Studies have also shown that these vaginal medications don’t increase risk of cardiovascular diseases or cancer. Some studies even suggest that low doses might be safe for survivors of uterine, cervical and ovarian cancer, although patients need to be closely monitored by a doctor.

For vaginally delivered hormones, “the box warning is not supported by science,” JoAnn Pinkerton, a gynecologist at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville said during the panel. The warning overstates risk and discourages patients that could benefit from hormone replacement therapies from using these medications, she said.

Multiple panelists shared stories of patients who were prescribed vaginal estrogen, but opted not to use the medications after reading the label. In many instances, these women had the benefits and risks explained to them by a health care provider, but they or their partners were still too afraid of the adverse effects described in the label to adopt the treatment.

Most of the studies showing the safety and efficacy of vaginal estrogen are observational, cautions Jen Gunter, an ob-gyn and author of several books on menopause. Observational studies happen when a patient gets prescribed a specific medication and then are followed to collect data on the outcomes of that treatment. They are less standardized than clinical trials, as Gunter points out in a video review of the FDA panel. Still, that doesn’t change the fact that the black box warning is based on the clinical trials of oral estrogen but being applied to vaginal estrogen.

Gunter agrees with the suggestion from some panelists to substitute the black box label with a warning similar to the one for Intrarosa, a medication based on a sex-hormone precursor that leads to similar blood-estrogen levels as vaginal estrogen medications. That warning says the medication is not indicated for women with a history of breast cancer or with undiagnosed vaginal bleeding.

Hormone therapy may have more benefits than risks for younger women

The Women’s Health Initiative, the original study on which the black box warning was based, studied heart disease prevention in post-menopausal women who were mostly over 60. It was stopped early because of evidence of harm.

The doses of hormones given in that study were many times greater than the low-dose estrogen and hormone combinations prescribed today, Aninye says. And the women were typically older. Women on average reach menopause — defined as one year since the last period — at age 51, but may experience many of the symptoms associated with menopause for up to a decade beforehand as the ovaries stop making estrogen, a stage called perimenopause.

Studies have suggested that pills and patches that deliver hormones throughout the body help women in perimenopause or early years after menopause get relief from hot flashes and mood swings and improve their sleep.

Hot flashes aren’t just annoying, they are the brain cannibalizing itself and releasing heat, Roberta Diaz Brinton, a neuroscientist at the University of Arizona in Tucson said during the panel discussion. During menopause, the brain stops using a sugar called glucose efficiently and instead starts using its own white matter for fuel. That produces hot flashes and inflammation in the brain and raises the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, she said. Hormone therapy can lessen hot flashes and night sweats for many women.

Some studies have suggested that hormone treatments may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease for women in perimenopause or early menopause. And estrogen helps prevent bone loss. Those are some of the reasons medical organizations and scientific and women’s health societies have recommended hormone therapy for women younger than 60 who are in perimenopause or within 10 years of starting menopause.

That doesn’t mean hormone therapy should be prescribed for every person who experiences menopause, Christmas says. The risks for women under 60 are generally low, but “it doesn’t mean that it’s zero, though, and people have a different tolerance for risk.” Women with a family history or genetic predisposition to breast or ovarian cancer may not want to take the medications, while those who wake up in puddles of sweat every night may decide the risk is worth it.

Women who go through menopause at 40 or younger get clear benefits from hormone treatment, including reduced risks of heart disease and osteoporosis. “But for people that go through natural menopause at the normal age range, we actually can’t say that there are those preventative benefits” for heart disease, Christmas says.

Ideally, women would discuss their symptoms, risk factors and treatment options with their doctors, but the black box warning effectively takes hormone therapy off the table, even for younger women who may benefit, Aninye says. “It just gives this overarching [message that] it’s unsafe for everybody, and so those conversations don’t happen more so out of fear than evidence.”

Much of the discussion concerning the risks of hormone treatments don’t capture nuances about the types of hormones used, their dosage or delivery methods, Aninye says. But some research suggests those factors are important. For instance, women with a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s had less buildup of plaques in their brains when they used a skin patch to deliver one type of estrogen than women who got a placebo or used a different form of estrogen taken as a pill, researchers reported in 2020 in Climacteric.

Disentangling the effect of menopause from those of aging can be difficult, Christmas says. So while estrogen may cool hot flashes and help women hold onto bone a bit longer, it can’t cure some of the brain and body changes that come with aging but are blamed on menopause. Hormones, she says, are not “anti-aging magic jelly beans.”

Read the full article here