It’s 10 minutes until the drug-testing tent at Beyond The Valley music festival is due to close at 7pm, but the small army of health workers and chemists are preparing to stick around for overtime.

The beating sun is sinking, but the festival is just reaching its peak. Thousands of young revellers – clad in bikinis, wraparound sunglasses and bum bags – are migrating down a dusty amphitheatre towards the thudding bass of the main stage, where they will dance through the night.

Festival-goers migrate to the stages at Beyond The Valley music festival. The Age is not suggesting anyone pictured used drugs at the festival.Credit: Chris Hopkins

There are at least a dozen punters in the waiting area at the testing site – ready to find out what’s in the illicit pills, powders and crystals they have brought to party for days into the new year. More are arriving, seeking results.

“If people keep coming, then we’ll just stay open,” says Cam Francis, chief executive of The Loop Australia, the organisation running the service.

It’s day two of the four-day festival held on remote farmland 45 minutes west of Geelong, and The Age has been allowed exclusive behind-the-scenes access to Victoria’s first pill-testing service while it’s in full swing.

There was a crowd of people waiting outside the facility on Saturday – the first day of the festival – before it had even opened its doors. By Sunday evening, when The Age visited, 300 tests had been conducted.

“They’re really taking to it quickly,” says Francis.

Within months of becoming premier, Jacinta Allan announced this trial after mounting pressure on the state government to act following a string of overdoses at music festivals last summer.

Signs to the pill-testing service.Credit: Chris Hopkins

Beyond The Valley, in its ninth year, is an obvious target for the service. It has a very young crowd – mainly in their teens and early 20s – and an openly celebrated drug culture among them. Hundreds carry around “doof sticks” – home-made signs on long poles with drug-themed jokes about doing MDMA, cocaine or ketamine.

One sign reads “Blinky Pill” alongside a drug-affected cartoon koala, while another has altered the yellow logo of a well-known fast-food chain with the words “Gacked and Gomez”. Used silver nitrous oxide bulbs (known as “nangs”) litter the festival ground, along with the odd discarded plastic drug “baggy”.

At the intake desk in the testing site, users are talked through the process before they meet a chemist in separated booths to hand over a sample.

They are asked what they believe the substance is and why they want to test it. The service is anonymous – no names, dates of birth or phone numbers are taken – and a random sample number is the only link between the person and the drugs. Once a user is given their number, they are free to return to the festival and come back for their results in 90 minutes.

Meanwhile, their samples are taken into a makeshift lab, where 10 chemists are ferreting through results.

In The Loop chemist Dr Riley Herron completes a testing sample to confirm a sample is ketamine, not cocaine, as the user believed it was.Credit: Rachael Dexter

During The Age’s visit, chemist Dr Riley Herron is asked to recheck a sample for a young man who adamantly believes he has been sold cocaine. The drug results show it is, in fact, ketamine.

Herron retests to assure him; the results show a match score of 962 out of 999.

Chemists need a sample only the size of a match head to be able to test the drugs.Credit: Simon Schluter

“That’s high confidence – it’s definitely ketamine,” says Herron. “If we get a score of about 700-ish then it’s a bit rough, and we know something else is going on.”

In a different pick-up marquee, groups of friends huddle on couches together and lean in to chat quietly with their assigned health worker.

The service advises everyone that there is no safe level of drug use, but the workers are realistic, presuming most of these young people know that and choose to take drugs regardless.

“So we’ll try to talk with them about reducing the dose, spacing things out, minimising how much they take, understanding signs of trouble,” says Francis.

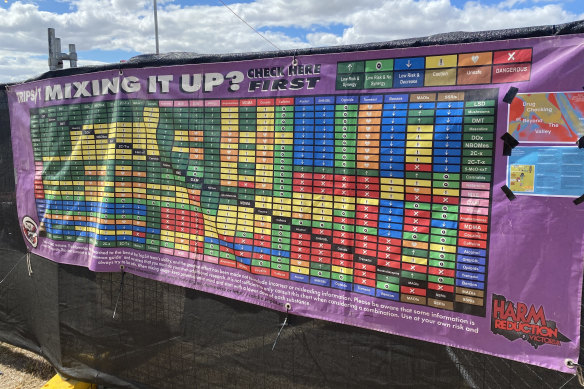

They are also offered advice about the dangers of mixing drugs. A huge banner outside the testing facility shows how 25 different drugs interact with one another.

The testing detects whether high-risk substances, such as fentanyl or nitazenes, have been mixed in with other drugs, which would trigger a festival-wide alert. As of Monday, no such dangerous substances had been detected.

More common are incidents in which partygoers take drugs thinking they are one substance when they are something else entirely, and then overdose.

Loading

RMIT’s Dr Monica Barratt, a long-time drug-harm minimisation researcher assisting the trial, recounts an incident at a festival last year when a group of four people sniffed what they thought was ketamine, but was heroin.

“They took bumps of heroin on the dance floor and they all dropped,” she said, adding they were brought back around by medics who used the opioid reversal drug, naloxone.

Just before The Age arrived on Sunday, two women found that the ketamine they had brought into the festival had benzodiazepines mixed in.

“They were keen not to take it,” says Barratt, adding the women said they intended to dispose of the drug.

Once the results are given, health workers don’t have any authority over what the festival-goer does with the substances, but users are asked whether they plan to bin the drugs, take less or take them as they had planned.

Overdoses also happen when the drug is known but revellers are unaware of “safer” dosage levels.

Francis says: “Our whole culture is an alcohol binge culture, and people tend to just apply that to drugs … they don’t understand how the risks increase exponentially.”

A man his early 20s was hospitalised after overdosing on the first day of the festival, but it is unclear whether he had used the testing facility because of its anonymity. He was discharged from Geelong University Hospital on Sunday.

A banner outside the drug-testing facility shows punters how different substances interact with one another. Credit: Rachael Dexter

Barratt says that after two days, the obvious drugs of choice have been MDMA and ketamine, followed by cocaine – but the complete data won’t be known until the festival ends.

Police revealed on Monday that a 28-year-old South Yarra man had been picked up at the festival with what is alleged to be 17 MDMA pills, four grams of cocaine, and seven other pills. He was charged with drug trafficking and bailed to appear in court in March.

One reason for ketamine’s popularity, according to Barratt, is that police roadside saliva testing – often conducted outside festival grounds – picks up only methamphetamine, MDMA and THC (from cannabis).

“There are a lot of other substances out there, right? But ketamine is a big one,” she says.

Unlike previous years of the festival, there have been no police sniffer dogs this year, and under new legislation, it is not a criminal offence to possess small amounts of illicit drugs while attending a drug-checking place.

Loading

However, police say they will continue to have a “highly visible” presence at the event.

“Police will continue to enforce against drug offences away from the drug-checking place and seize any illicit substances,” they said in a statement. “As always, police may use discretion to not enforce possession offences.”

Francis says his ambition is that over time, drug testing will “start to shape the drug market”, get toxic drugs out of the supply chain and lower instances of overdose through education.

“We’ve got a long way to go to get it to the scale that we really want to, but I think we’ve made a good start,” he says.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Read the full article here