When Kai Kinsley was thirteen, he caught a relative sexually abusing his sister. It set him on a mission to hunt down pedophiles.

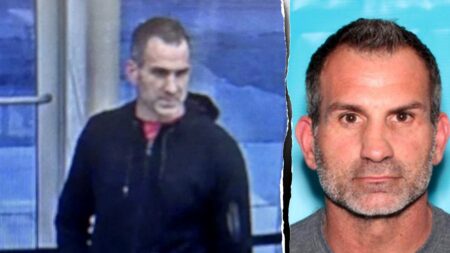

Now 22, he goes by Omma on YouTube, where he posts videos of himself catching alleged pedophiles who he has been chatting with online through decoy underage accounts.

“At first I found [talking to pedophiles] disturbing, but after so many meetups and calls, you just hear everything, and it kind of becomes one big gross bubble that it’s easier to dissociate from. I do what it takes. I care,” Kinsley, who has 1.3 million subscribers and has made a full time career of his pursuit, told The Post.

Kinsley is part of a growing number of online vigilante pedophile hunters, who use decoy accounts to lure alleged predators into “meetups,” then post videos of confrontations. Often, the police are called and arrests are made.

It’s the DIY version of Chris Hansen’s NBC show “To Catch a Predator.”

Kinsley’s stings have resulted in as many as a half a dozen felony charges, including accosting a minor and using a computer to commit a crime, according to The Hastings Banner, a local paper in Michigan.

Kinsley creates slick videos which deploy graphics and hidden cameras to create his show for YouTube. While he and some other YouTubers have been successful in putting away creeps, there are growing concerns about extrajudicial “pedo hunting” and the blurring of police work and creating shows for entertainment.

Though law enforcement officers also pose as minors online, experts say that there are major due process concerns when influencers barrage, accost, publicly shame, and sometimes assault the accused.

Network shows such as “To Catch a Predator” were made in collaboration with local law enforcement, who advised and supervised sting operations. Still, that show was cancelled in 2008 after a target took his own life during a sting, and by that time it had also been hit with legal and ethical complaints.

Untrained everyday citizens can often fail to follow the law and protocol properly.

In an especially brutal example, Ahmad Wasfi Al-Azzam, who called himself “realjuujika” online, allegedly broke in to a 73-year-old man’s home, beat him with a hammer, and robbed him of his credit cards for soliciting sex from a teen boy — all on live stream.

The man was hospitalized and required surgery. According to the New York Times, the incident was one of more than 170 violent vigilante attacks by vigilante pedophile hunters since 2023.

Late last month, three social media vigilante members of the Oklahoma Predator Prevention were arrested and charged with unlawful restraint and exposure to substantial risk of serious bodily injury after one of their targets lost consciousness.

“Confronting suspected predators without proper training or proper law enforcement support is extremely dangerous and can result in escalation, unintended harm to the surrounding community, tainted evidence and interference with criminal investigations,” a press release from the McLennan County Sheriff’s Office noted following the arrests.

Kinsley disavows this behavior: “There are absolutely people who aren’t serious and make it into a prank for TikTok or for clicks, rather than going for permissible evidence. That’s unfortunate, because, if you’re going to do this, you have to do it absolutely the right way.”

He’s been setting men up on camera for four years — since he turned 18 — finding them on apps like Discord, MeetMe, and Kik.

“When these guys don’t have any matches on Tinder, they go to another app. The more obscure the app, the more obscure the people,” he said. “I realized there are a lot of bad people on these platforms, and I just got enthralled in doing what I could to help with that.”

He can spend between a day and several months messaging via a decoy account before a predator starts becoming sexual.

“They start to kind of push the barrier once they feel a little more comfortable, so they kind of digress to, ‘Oh, what are you wearing?’ Or ‘What have you done sexually?’” He explained, “They want to know the parents’ schedule so they know when they can have more access.”

Then, he’ll either plan to meet up at the predator’s house or invite them to meet at a decoy house, when he stages an intervention, approaches the predator himself and tries to talk to him as security lays in wait.

“Some guys do run out, and we can’t restrain them, but for the most part, guys will generally sit down and kind of have a conversation about it,” he explained.

When Kinsley feels he has enough evidence, he says a code word, and one of his security team members calls the cops. When they arrive, he gives them a hard drive full of evidence related to the case, and they typically arrest the alleged predator.

“The cops do really great work, but they can only do so much,” he said.

Kinsely estimates he’s had twenty successful “catches,” and says his fans are grateful for the work he does.

Matthew Stegner, a retired New York State Police Officer on the Internet Crimes Against Children task force based out of Erie County, says that some YouTubers are providing adequate evidence.

“In fairness to these streamers, they are often establishing probable cause that a crime has occurred, and they’re recording it, so I’m not surprised that the cops are taking it seriously,” he said.

But he’s also concerned that tactics like showing up at an individual’s home could go south.

“They really need to make sure that they’re dealing with the right person at the right residence. If they’re wrong, the consequences could be devastating,” Stegner told The Post, adding the Castle Doctrine, which allows someone to stand their ground defending their property, could put them in particular danger.

“I have a bad feeling one of these is going to end up horribly. Worst case scenario is that one of the streamers or YouTubers is going to get killed,” he said.

Michael Aterburn, who worked as detective investigating internet crimes against children in Jefferson County, Kentucky, for six years, agreed there’s a massive safety issue.

Every cop that would show up to confront a predator was armed. “Even the decoy [pretending to be a minor] was an armed officer,” he said, noting many of these men are highly dangerous, and he’s taken handcuffs, valium, ropes, knives, and guns off them after arresting them.

“I think it’s too much of a risk to not only themselves, but bystanders, I mean, if you’re meeting at a Walmart parking lot or a park where a kid could be on a bicycle, there could be a shooting,” he said.

“These YouTubers are filling a need that should be done by law enforcement — somebody with a badge and a gun.”

But Arterburn lamented that there could have been ten times as many men on his task force posing as minors online, and they still wouldn’t have been able to catch every predator.

Stegner agreed, “The public is frustrated at the volume of pedophiles that are out there, and I think they’re frustrated by a lack of accountability. It could just be for clicks, I don’t know, but it seems like the outrage is genuine enough that [these YouTubers] are taking action.”

This lack of accountability, Kinsley says, is what makes it worth taking on risk himself.

“I’m committed to what I do, even if there’s a little bit of danger involved in it,” he said. “That’s just the nature of the job.”

The response he gets from fans is all the thanks he needs: “I get emails from survivors of abuse, and they say, ‘I wish someone like you had stepped in when the police didn’t, I wish someone had put my abuser on blast.’”

Read the full article here