If Sita Sargeant followed the path that was written for her, she’d probably be halfway around the world right now.

She would be finishing her PhD in South Asian studies. Instead, she is striding through Melbourne’s CBD in jorts and a pink T-shirt, giving women erased from the city’s history a “hero’s journey”.

She is also busy thinking about a remodelling of her brand-new basement office.

“We’re thinking of doing pink carpet and pink walls, so it looks like a vagina,” she says, grinning and gesturing grandly in the foyer of the Queen Victoria Women’s Centre.

The context here is that the centre is the starting point for Sargeant’s “She Shapes History” tours, which began in Melbourne in June, about a month after she moved here from Canberra.

To her tour guests, she reveals Melbourne as a place built on the backs of “badass women”.

The city, in turn, has revealed itself to her as the kind of place where the local women’s centre offers a 20-something lesbian working in feminist history free office space in its basement.

Each of Sargeant’s tours starts with a question, which sets up the central proposition of her growing social enterprise: “Tell us about a woman you admire.”

Ask the same of the grizzliest-looking guy, in the most remote pub in outback Australia, and he’ll be able to give you three answers, Sargeant argues – probably his mum, his teacher and his wife.

“On a really personal level in this country, we do respect women,” Sargeant says.

“We don’t do that at a local level, we don’t do that at a state level, and we don’t do that at a national level.”

Take Victoria, for instance: fewer than 10 per cent of its places are named after women (although the state is named after Queen Victoria), and of Melbourne’s 580 statues, an “appalling” number – just 10 – are women, Sargeant says.

But her tours aren’t about brooding on this sad reality, or shouting angrily at monuments (although, it is enough to provoke outrage).

Instead, they’re an earnest celebration of women, bringing their untold stories to the forefront of the city – and there’s rich history everywhere to see.

Catch a tram to the women’s centre?

Well, Melburnians have Isabelle Clapp to thank for that, after she and her husband – inspired by emerging tram technology overseas – lobbied the state government to set up the city’s first cable tram network, and secured the contract to build and operate it in 1883.

It wasn’t until a whole century later, though, that Joyce Barry was allowed to become Melbourne, and Australia’s, first female tram driver. She trained for the job almost 20 years earlier – prompting the entire tramway union to go on strike.

Barry declared at a union meeting: “I don’t need a penis to drive a bloody tram.”

Then, there’s the women’s centre itself: an imposing heritage tower with Lonsdale Street frontage, the birthplace of the former Queen Victoria Hospital for women and children in 1896.

The hospital was founded by Australia’s most over-qualified – and underemployed – doctor of her time: Constance Stone, whose rejection from the University of Melbourne medical school (which didn’t accept women) drove her to get not one, but two, degrees in the United States and Canada.

She presented her degrees to the Medical Board of Victoria, which refused to register her as a doctor on grounds they didn’t accept qualifications outside the British colonies. Feminist historian Barbara Wheeler believes if Stone were a man, she’d have returned to Australia a highly qualified doctor.

Instead, Stone ventured to the United Kingdom, this time returning with a third and fourth degree – and ultimately becoming certified as Australia’s first registered female medical practitioner, when the board could no longer deny her qualifications.

But, because she was a woman, nobody would hire her. “There were absolutely no offers of a job, no appointments – nothing,” Wheeler says.

Stone built her reputation by running free street-side clinics, and – inspired by her work with London’s pioneering doctor, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who co-founded the New Hospital for Women in 1872 – she eventually set up Melbourne’s own women’s hospital alongside her sister, and other women doctors. They were finally permitted to study at the University of Melbourne during Stone’s first year of practice.

The story is a testament to how hard women had to fight, even for the right to aid Melbourne’s most vulnerable.

Sargeant explains she started She Shapes History in Canberra in 2021 – during Australia’s #MeToo movement – out of frustration over women’s lack of recognition in Australian history.

“I was honestly just really fed up,” she says.

“I was finding these women, but they were never positioned as central characters. That speaks to that lack of respect for women: the fact that we don’t give women a hero’s journey, and that we don’t let women be really full figures.”

Marching through the streets of Melbourne, Sargeant materialises these figures.

At a modern-day hotpot restaurant on Swanston Street, there’s Val Eastwood, who created one of the city’s first public spaces for queer people, while wearing her signature men’s suits and red lipstick, and carrying a silver-topped cane.

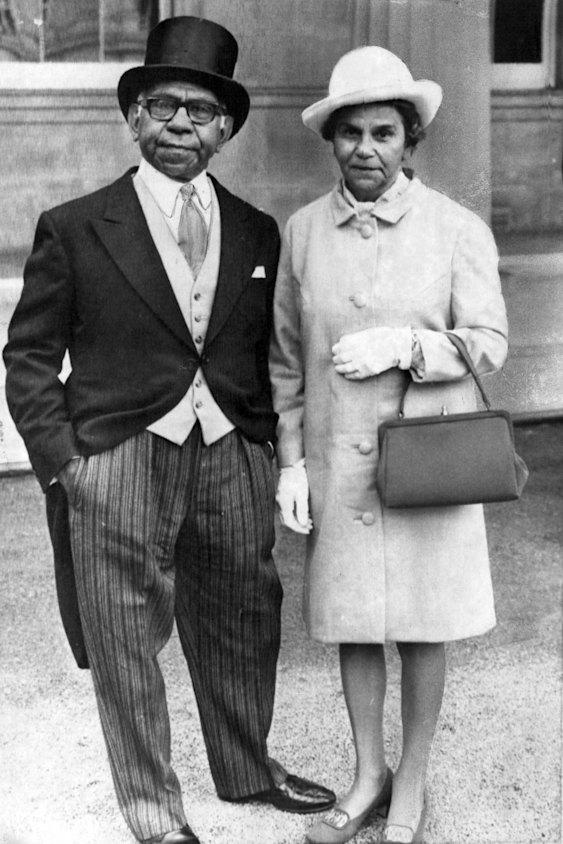

In Parliament Gardens, there’s Aboriginal activist Gladys Nicholls – a personal favourite of Sargeant’s – who, alongside husband Doug, was a pivotal force in campaigning for the 1967 referendum for Aboriginal rights.

The activist was, unbeknown to most, half Indian, like Sargeant.

Nicholls ran her own social enterprise: a group of op shops in Fitzroy – which Sargeant describes as the “most Melbourne thing ever” – to fund hostels for vulnerable Aboriginal women.

“[The tours are] a good reminder that you don’t need a penis to shape history … and that all of us are shaping history in different ways, whether it’s through building community, through having dabbles with the law, through parliament, through creating op shops,” Sargeant says.

“Melbourne is filled with really eclectic women who have hustled and built this city.”

Sargeant barely stops through a speed-run of the tour, walking quickly through pedestrian crossings within seconds of their lights turning green, and speaking emphatically.

At Parliament Gardens, though, she sits on a bench under the shade of trees opposite Nicholls’ statue. She looks up at her bronze figure, and, for a moment, there’s silence.

She Shapes History public walking tours operate every Saturday and Sunday in Melbourne’s CBD. Find out more on their website.

Our Breaking News Alert will notify you of significant breaking news when it happens. Get it here.

Read the full article here