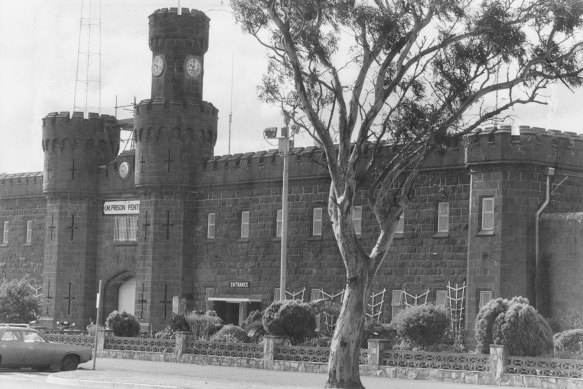

A couple of years ago, I attended the launch of a book written by two former armed robbers, held in the upscale housing development that was once HM Prison Pentridge in north Melbourne. The defunct jail’s bluestone walls and neo-Gothic gatehouse still echo with menace, but the guard towers look benignly over a shopping centre and cinema, two hotels, and more than 300 modern apartments.

On the day of the launch, elderly hardmen with macerated noses and disappearing tattoos exchanged pumping handshakes and crushing hugs. It was like a high-school reunion – although the type that is menaced by a deranged slasher, rather than the kind where teenage romances are rekindled.

The book, Born into a Lie of Crime, is the memoir of former gangster and amateur boxer Ron Isherwood, 72. I assumed Isherwood had enjoyed the launch, but when I ask him about it today, he says it made him sick. “I remembered how I had to walk into the place as a 17-year-old kid,” he says. “The horror of the place, the smell of it … everything about it was like a bad nightmare. I went back to the cell where I was beaten up by the screws, and it all came back to me. In one second, you’re back there as a tiny, little insecure boy. They walked me out in the yard, and I remembered guys being sexually abused in the yard and the screws sitting in the tower watching: they didn’t care.”

He pauses. “I hate the joint,” he says.

A BrewDog bar now operates on the

site of E Division.Credit: Josh Robenstone

At Pentridge Coburg, the muster yard is now a piazza with a children’s playground. There’s a BrewDog bar serving craft beer where the E Division once stood. The punishment wing at H Division now hosts guided tours. There are wine cellars in what once was D Division, where connoisseurs can buy storage for their own collections in temperature-controlled cells (and at least one ex-prisoner has taken advantage of the facility).

But even before Pentridge Coburg fully opened in November 2020, former inmates regularly returned to the site. Perhaps the most comfortable among them is former armed robber Doug Morgan, now 71, who served 11 years in Pentridge and can now be found at BrewDog almost every weekend. Here, he chats to customers, paints pictures, and sells handmade key fobs painted with Ned Kelly helmets and fashioned from bluestone chips harvested from the rubble of B Division, where serious offenders (including Kelly, in 1873) were usually housed.

He’s often around during the week, as well, working on a canvas. “If you’re painting a Ned Kelly or something else that relates to crime,” he says, “it feels interesting to at least start or finish the painting in jail.”

In his criminal career in the 1970s, Morgan was dubbed the “After Dark Bandit” and appeared to possess the uncanny ability to rob two different places at one time: it turned out he was raiding TABs in tandem with his twin brother, Peter.

The gateway to Pentridge in 1981. The prison continued to operate until 1997.Credit: The Age Archives

Prisoners in a Pentridge exercise yard in 1978.Credit: Fairfax Photographic

Doug Morgan has had other nicknames, too, given he arrived in B Division almost exactly a century after Ned Kelly. “Lately, they’ve started calling me the ‘Last Bushranger’,” he says. “So the Last Bushranger painting Ned Kelly on bluestone from B Division … if you wrote a script like that, people wouldn’t believe it,” he says.

He taught himself to paint in HMP Pentridge, and he would exchange his paintings with other prisoners for cigarettes, which he would sell for cash. Today, he gives some of the money he makes to charity, and Pentridge is “just part of my life”, he says. “I’m very comfortable to walk back through it because I don’t have any fear of it. Sometimes I sit in BrewDog and look around, thinking what a relaxed place it is when it’s not a prison.

“A jail is a place that holds prisoners,” he adds, “and if you take the prisoners out, it’s just a building that might have cells. Walls and floors are not violent. The violence and the brutality come from the people around you – on both sides.”

Morgan is a builder by trade. “In a strange way, when you walk into B Division, the building itself is quite attractive,” he says. “I have a chance now to look at the architecture and workmanship of a 170-year-old jail, which I probably didn’t have time to look at when I was there. I was probably more worried about other things …” He seems at peace with Pentridge. “The only bad feelings I have about jail is the fact I put myself there,” he says. “I wrecked my family. I deserted my children. They were raised by another man.”

He was not always so relaxed. When he was a prisoner, he tried (and failed) to escape and came under fire from a guard tower.

Doug Morgan taught himself to paint during 11 years inside Pentridge.Credit: Josh Robenstone

When he meets former prison officers, he says, “I still give them the same lip and attitude that I did then. I didn’t have any respect for the uniform.” But he does not bear a grudge. “Even if I’d been punching on with screws, my attitude was the same as the old days in the pub: you can punch on in the pub, and then you sit down and have a drink.

“I’ve had beers with prison officers in the last six months and laughed and joked about different security issues that I was involved with,” he says. “Maybe three months ago, I was having a chat with a prison officer who was on another tower on the day that they were shooting at me. He still vividly remembers the scene of me being shot at and then surrounded by a whole heap of screws.”

‘It’s bizarre but there’s almost a degree of the sacrosanct about it, for those who’ve been there and lived it.’

Glenn Broome, lived-experience consultant for Victoria Legal Aid

Morgan doesn’t feel like a victim. “We weren’t the good guys; we were the bad guys,” he says. “It seems to me a bit ridiculous to be talking about brutality because we were all in jail for what we did to people on the outside.”

Former armed robber Glenn Broome, who is now a lived-experience consultant for Victoria Legal Aid, served time in Pentridge with Morgan in the 1980s. “I’ve been back a couple of times,” says Broome, 62. “I went and saw a movie once. I don’t mind the open areas, but I don’t like H Division. It takes a while to orient yourself because so much of it has been torn down.”

Loading

He feels that a lot has been lost in the building work. “There’s room for progress,” he says, “but the way people wandered through, it was almost like a grave being desecrated. It’s bizarre but there’s almost a degree of the sacrosanct about it, for those who’ve been there and lived it. Even a brick will bring back a memory.”

His mate Morgan has no time for that kind of sentiment. “A lot of prisoners complain about what’s happened to Pentridge,” says Morgan. “Who cares? Society doesn’t care.”

Broome is less placable. “You’ve got people that are emotionally tormented,” he says, “and the thing that I struggled with was to walk back in there on a Saturday afternoon and see these hypocrites using the cellar as a wine chiller.”

Veteran escape artist

Ron Isherwood’s book Born into a Lie of Crime is edited by Australia’s best-known prison escapee, John Killick, who absconded from Silverwater Correctional Complex in NSW in a helicopter hijacked by his Russian lover Lucy Dudko in 1999.

I was with Killick at the Pentridge launch, when he and Isherwood took a tour group (including some prisoners) on a walk through the worst days of their lives.

Killick is a serial fugitive. While jailed in E Division in 1968, he hit a prison officer, stole his pistol and demanded a flight to Cuba. The police laid siege to the prison, but he surrendered before they could storm the cellblock.

Killick was in and out of banks and jails for much of his adult life. Doug Morgan has painted his portrait, which is now on display in Geelong Gaol Museum. These days, Killick, 83, is a dapper and personable fellow, but Morgan’s image of him is jagged and frayed. “He doesn’t like the portrait,” says Morgan, “because I was showing the harshness in his face, and I was trying to portray that he had a wasted life. He doesn’t want to look like that; he wants to look bubbly. But that’s bad luck. I’m the artist.”

When Killick was recaptured a few weeks after that helicopter escape from Silverwater, he was sentenced to 23 years’ imprisonment in NSW, of which he served 15 before being paroled in 2015. Soon after his release, he was keen to return to Pentridge and promote his writing.

Loading

“I had offers to go down there quite often,” he says, “but my parole officers were proper bastards. They would not let me out of the state for the whole 23 years.”

One week after he had served out his parole in NSW, he says, “I was out of there, printing up T-shirts saying, ‘I’m still here, you bastards’. I walked around Pentridge wearing the T-shirt … I was selling books outside E Division where I’d escaped and hit a screw over the head.”

He was put up by sponsors in the five-star Adina Apartment Hotel Pentridge. “From the hotel, I could look down at night, right down to where E Division was, where the siege took place and 18 carloads of SWAT teams came in,” he says. “I was lucky to stay alive.”

And what was he thinking? “I thought, ‘Fifty years ago, who would have believed I’d come back here like this?’” says Killick. “And it was just a great feeling.”

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and Brisbane Times.

Read the full article here