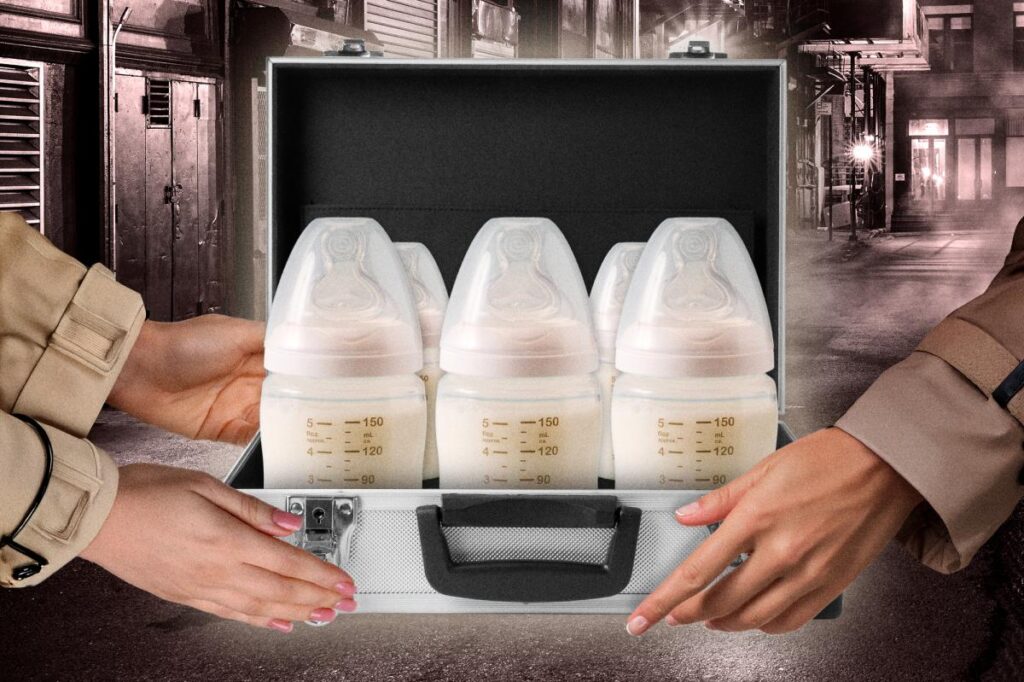

Don’t cry over spilled milk — but be careful where your baby’s next sip comes from.

In the last decade, interest in sharing breast milk — both formally, through milk banks, and informally, within close networks — has seen a spike among new parents.

In a 2017 statement, the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine noted that informal sharing had become “increasingly common as 21st century families’ desire to feed their infants with human milk increases.”

But while donor milk can have major benefits when needed, not all methods of obtaining it are created equal.

Julie Ware, MD, president of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (ABM), tells The Post that human milk “not only provides optimal nutrition, but it provides immune protection for the human infant.”

But transporting breast milk isn’t as simple as shopping for a carton of 2%. The same properties that make breast milk so essential for newborns are what make it potentially dangerous if mishandled, especially when it’s not going to be consumed fresh or it’s coming from a source other than a baby’s own mother.

Human milk banks are common, and accept donations from nursing parents who have an excess of milk for whatever reason, whether they’ve produced too much for their own baby, their baby has an illness that prevents them from breastfeeding, or their baby has died.

At a standard milk bank, milk donors are first screened for HIV, Hepatitis B and other infectious diseases, as well as for use of drugs, alcohol and any medications that are incompatible with breastfeeding, according to Ware.

After the pre-screening, the bank will test the milk for bacteria, drugs and pathogens, and will then pool it together with milk from several other donors before eventually pasteurizing it.

But some emergency situations don’t allow for that level of care and precision.

Why would a baby need someone else’s breast milk?

In Minneapolis this month, for example, some mothers have been compiling their own makeshift milk banks to provide food for infants whose mothers have been detained by ICE.

According to The 19th, one 3-month-old baby, whose mother was taken from her car on her way to work, had not eaten for a day and a half. She was exclusively breastfed and refused the formula that her teenage sister had tried to feed her in the mother’s absence.

A neighbor who had recently started freezing her own breast milk to donate to impacted families showed up with a cooler of milk and instructions for how to thaw it from frozen.

Plenty of other circumstances can stop a mother from producing breast milk for her child as well.

Some women die in childbirth or otherwise fall ill, preventing breastfeeding. Milk may be delayed if a baby is born prematurely, or a mother can have limited supply due to other health issues. Donor milk can also be used in cases of adoption and surrogacy.

Why not just use formula?

If separated from their mothers, some babies who are exclusive breastfeeders may refuse a bottle, leading to severe dehydration and stress, Ware explains. And “without the protection of human milk, they have an increased risk of a multitude of infectious diseases,” plus things like diabetes, asthma and even childhood cancers.

It’s not just bad news for babies. There are potential medical complications for nursing mothers who are not able to breastfeed, too, Ware says.

In the short term, they can expect significant breast pain and engorgement, possible mastitis and psychological distress. In the long-term, they face an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancers and various heart diseases.

How safe is it to share breast milk?

Ware says that whenever possible, babies shouldn’t go without their own mother’s breast milk.

“We call it personalized medicine — it’s perfectly matched for the infant’s needs,” she says. “The mother makes breast milk that her specific baby needs.”

Donor milk, whether frozen or pasteurized, is not going to be as “amazingly personalized” for the baby recipient as milk from the baby’s own mother, Ware says, “but in the list of preferred milk, it’s leagues ahead of commercial formula because of the other immune factors that it has.”

Storage guidance from the ABM says frozen milk, though safe to use for three months, will have diminished bioactivity compared to fresh milk, and a decrease in fats, proteins and calories.

Still, they said, “When direct breastfeeding is not possible, stored human milk maintains unique qualities, such that it continues to be the gold standard for infant feeding.”

The safest option for milk sharing is to go through a milk bank, with its routine operating procedures and thorough testing. The FDA, the Human Milk Banking Association of North America, and the European Milk Bank Association all discourage informal milk sharing outside the scope of a milk bank — but sometimes, formal outlets aren’t available.

One method of milk-sharing that experts resoundingly condemn is the online sale of breast milk, which “can be adulterated with other substances or arrive fully thawed out, spoiled and contaminated with various bacteria,” according to the ABM.

“Since the breast milk that is being sold on the internet is being sold for profit, the donors may not be fully transparent regarding their health histories, medications and social practices, thereby increasing the risk to the recipient infant.”

What’s the verdict?

Milk from a trusted source, especially pasteurized or frozen, is a good bet. But a baby’s best bet will always be fresh milk from its own mother.

Lactation experts call this dynamic — a baby nursing from its mother — a “nursing dyad.”

“They’re two persons enveloped in one when nursing together,” Ware says. “If you remove a piece of the whole, it’s going to interfere with both of them.”

Read the full article here