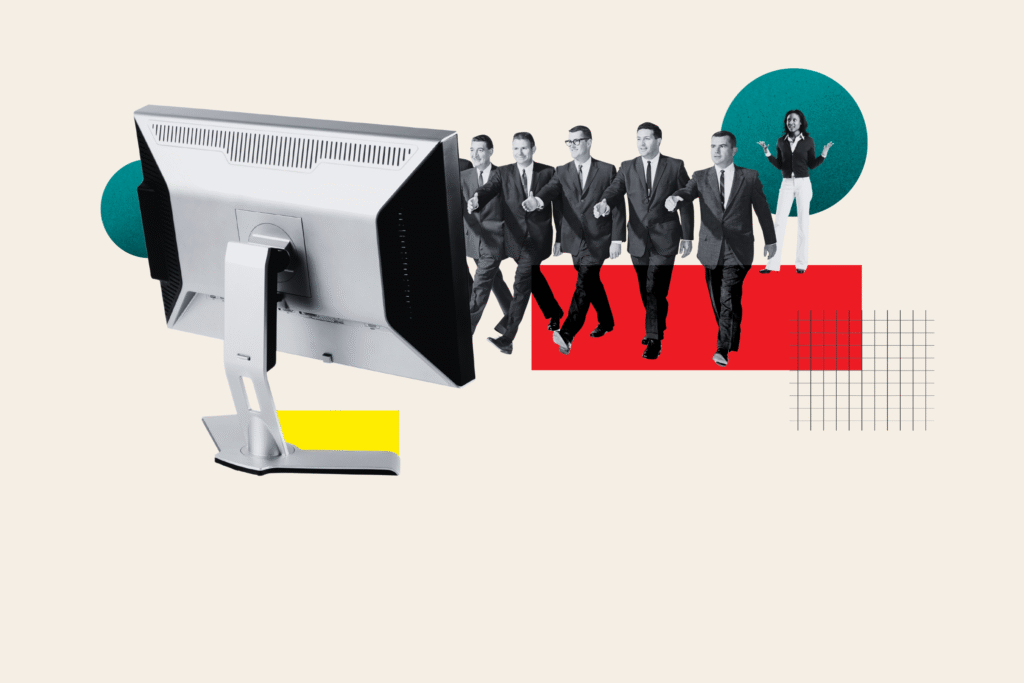

Reaching equitable gender representation has remained an elusive challenge in the tech world. Despite decades of promises to make the world a better place and democratize opportunity, the tech establishment and its investors have not delivered.

Just 3 percent of venture capital investment in 2024 went to solely women-owned businesses, and just 26 percent of the Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index CTO or CIO positions are held by women, according to a 2024 analysis by Russell Reynolds Associates.

“The main issue, I think, is unconscious bias,” Francine Gordon, management professor at Santa Clara University’s Leavey School of Business, told Newsweek. “I think that has a lot to do with why women in tech tend to leave. … They don’t see upward mobility, and a lot of that is because of unconscious bias.”

She added that these biases affect key career moments such as hiring, performance reviews, promotion conversations, leadership searches and investor pitches.

The tech industry has long viewed itself as different from the business titans of yesteryear. After the dot-com boom and bust, optimism soared around the ability to rapidly share information and work more productively, thanks to software, the cloud and, later, augmented or virtual reality, machine-learning and generative AI. This optimism drove heavy investments and high salaries and birthed a new culture, headquartered in Silicon Valley, with profits soaring as the world evolved from analog to digital.

With great profits came job security, prestige and hefty compensation packages, driving glamorization of STEM fields to students and early-career professionals. But it has also driven exclusivity.

Alongside this push, women were encouraged into science and technology fields, through programs like Girls Who Code, or into entrepreneurship, by funds like Anu Duggal’s Female Founders Fund or Jesse Draper’s Halogen Ventures, but those efforts have been overshadowed by a persistent inequity driven by societal, organizational and financial pressures, according to recent research.

A 2024 survey of women working in tech by Web Summit found that 50 percent of women reported experiencing sexism in the workplace, while half of women (49 percent) also feel pressured to choose between family and career.

“Respondents identified unconscious gender bias, balancing career and personal life, the scarcity of female role models, imposter syndrome, lack of support networks, and difficulties in funding as their most significant challenges,” the report stated.

Institutional Bias and Support

After completing her Ph.D. in organizational behavior at Yale, Gordon was part of the first “wave” of two female faculty members at Stanford University’s business school.

When they started in 1972, she said, it was a “very hostile environment,” adding that her lone female colleague, Myra Strober, had people walking out of her classes because they didn’t want to be taught by a woman or hear women’s ideas.

Gordon also recalled that office secretaries had to be reassigned because some didn’t want to work for her, highlighting how even women can internalize bias. Through the struggle, she learned the importance of friends and allies at work.

“I don’t think people meant it to be hostile, but it really was. [Strober] and I became very good friends,” Gordon said. “If you’re the only one, it’s very hard to succeed. Everybody’s watching you, and you also have the sense of, “If I don’t do well, everybody’s going to think all women are bad.”

Gordon later worked in management roles at Pacific Bell, Ungermann-Bass and Boston Consulting Group before starting a consulting firm called Womennovation. She emphasized the importance of mentorship and sponsorship in the advancement of women’s careers in tech.

An article in a 1992 issue of Stanford Business magazine quotes Strober saying that with a supportive dean in place at the school, “[women] began to apply in large numbers. … It was difficult for many of our male colleagues to understand that we were the beginning of a social revolution. I’m not sure that we understood it ourselves!”

Gordon notes that “things are much better now,” though a slight reversal has occurred over the last few years, amid a new presidential administration and its high-profile collaborations with the tech industry.

“People are more resentful of women who have advanced,” she adds, noting that DEI has come under a microscope as part of a multiyear advocacy movement. “There’s been an increase in attacks on people who are different, and it’s really widespread. Everyone thinks California is so liberal; we have a lot of hate groups here, too, and I think it’s been encouraged to some extent.”

Gordon also mentioned concern around seeing well-known leaders making public commentary that is anti-woman, anti-immigrant and anti-LGBTQ, contributing to a culture that skews toward labeling anyone in an out-group as inherently unqualified.

Melissa Faulkner, CIO at the global construction company Skanska, points to strong mentorship and a culture of diverse leadership that allowed her to reach the CIO post in 2021.

“I’ve been fortunate to have a lot of incredible mentors during my time here at Skanska and even previously,” Faulkner told Newsweek. “We’re a servant leadership company. We have a lot of empathy and are really focused on empowering teams.”

Faulkner also noted her company’s strong female presence in leadership as an indicator of an inclusive culture.

“Our executive leadership team is made up of more than 50 percent women. … We have strategic operational leadership, where there’s women running our business and running P&L. So I do feel like Skanska is a place to be celebrated for how women have been able to stand in leadership positions.”

Tracking the Data

Without proper measurement, many companies are likely to be in the dark about the state of gender equity within their own companies. Financial consulting firm Grant Thornton has recommended tracking turnover data by gender, finding in 2024 that just 22 percent of tech companies do so, and keeping close tabs on pay equity as well.

However, representation itself should not be the lone goal, as Mary A. Armstrong and Susan L. Averett, professors at Lafayette College, wrote in a paper that bore the book Disparate Measures: The Intersectional Economics of Women in STEM Work.

“They’re partial solutions,” Armstrong said in an interview on a New Books Network podcast. “Part of the true lies of STEM is that we let ourselves imagine that opportunity and access or the power of diversity … [are] complete solutions, but they’re not. They’re only partial solutions. They matter, but they don’t correct the larger system that disadvantages women in the labor force, including in the STEM and STEM-related workforce.”

Disparate Measures also asserts that it is a myth that women do not seek STEM roles or leadership and that by simply encouraging them to enter the utopian techno-meritocracy that lives in the minds of tech investors and leaders, we can meaningfully address gender equality. Faulkner shared a similar thought as well.

“We’ve always been interested in technology, but now there’s a visibility component where there wasn’t before,” she said.

Faulkner also noted that it wasn’t as much about knowledge or access as it was those early STEM environments, such as science and math classes and extracurriculars in school as well as entry-level jobs.

“Knowing that’s a role and a place that they can have a career starts really early in education. … For so long, it really wasn’t a very inclusive environment where women who were interested were welcomed, if you will, into technology. That has really changed a lot, but it starts early on,” she said.

Armstrong and Averett’s book highlights, among other challenges, difficulties in finding reliable data across time, the lack of parental support in the United States and unequal treatment of women as well as immigrants and people of color as the vectors for ongoing inequality in STEM.

“Often we discuss STEM jobs as if they are some sort of magic set of occupations that live in the ether and function in a way that is entirely distinct from the rest of the labor force,” Armstrong, a gender studies professor, said. “We are perhaps in a habit of pretending that STEM work is not wired into all the other systems of inequality that shape society. [But] STEM work is not exempt from these dynamics.”

The category of STEM-related work—roles like nurse or health care technician that require high levels of skill and certification but are not considered “core STEM” roles like those in engineering—Armstrong and Averett note, has strong female representation but is also correlated to lower earning potential, effectively segmenting women out of the higher-earning fields.

“[STEM-related jobs] are diverse in training and technical demands, but they’re often omitted from policy research discussions,” Averett, an economics professor, said. “It turns out women in STEM-related work are potentially concentrated in lower-paid roles, which reflects persistent patterns of occupational segregation.”

So, while many of the issues of inequality persistent in tech are persistent in society writ large, the tech industry benefits from certain protections—such as idealism and sky-high profits—that have allowed it to propagate inequality, both socially and within its workplaces. Unless societal issues are addressed, working in tech or STEM will be like working in any other field, or maybe worse if concentrated power goes unchecked—it’s not the utopian meritocracy that many believe it to be.

Read the full article here